The operator of a powered jigsaw cuts a slot in a small steel part for a warplane in a Brooklyn, New York factory. The slot must be precisely right and, to inspect it, the workman runs his fingers over it.

In a Manhattan workshop, a group of men reclaim tons of aluminum in the form of rivets that were swept from the floors of aircraft factories and shipped to them in barrels. The men sort the rivets into 50 various sizes for reuse in the war.

In another war plant, women file and sand bullet dies. Others operate power sewing machines that turn out heavy canvas aprons and uniforms for the use of Army chiefs and the Quartermaster Corps.

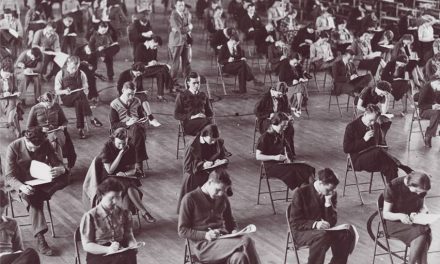

These workers have more in common than the fact that they contribute to the war effort—they all have disabilities. Since the U.S. involvement in the war, the disabled have entered the work force to help towards the war effort.

More able-bodied men are entering the military each day, at a rate of 10,000 to 30,000. Nearly 300,000 men were inducted in May, which is an all-time high. These increases have posed challenges for the companies that are providing materials to American and Allied forces.

In order to combat these labor shortages, the work force in various fields has expanded to include millions of women, African-Americans, immigrants, and, most remarkably, the physically and mentally disabled. Employers formerly considered such workers unfit for most jobs.

Approximately 3 million disabled men and women – the blind, deaf, physically impaired, and others – are now engaged in the war industry.

A survey conducted by the Northwestern National Life Insurance Company shows how the employment of disabled persons has increased. From 1940 to the end of 1941, disabled employment grew by 50%. From the end of 1941 to May of 1942, disabled employment grew by 300%. This means that the employment of the mentally and physically impaired has risen much more rapidly than the overall employment rate in the country.

This may seem surprising. How can individuals who are missing limbs, cannot see or hear, or are suffering from disorders possibly be essential to the war effort?

To answer that question, consider the example of deaf women, who are operating power machines, working in leather and metal trades, and carrying out electrical wiring and assembly. These women have learned sign language and it contributes to the fast movement of their hands and fingers. Also, because these women have less than 10% of their hearing – which is required to be considered deaf or close to it – they are barely interrupted by external noises and distractions. They possess incredible concentration that leads to thorough execution of their jobs.

The blind, like the deaf, also have heightened abilities that are useful in the war industries. In 54 workshops throughout the country, 2,600 blind men and women make brooms, deck swabs, overalls, pillowcases and sheets for barracks and government hospitals. Several hundred more blind men are employed in plane factories and in war plants that work on military radio parts. Students at the Louisiana State School for Negro Blind are taking part in the war effort by knitting sweaters and other articles of clothing for the Red Cross. According to J.F. Clunk, Chief of Services for the Blind, the blind can run almost any power machine that only needs manual direction and is not operated from blueprints. Despite lacking the sense of sight, their sense of touch is amplified above normal.

Wounded men and women, and those who have lost limbs on the war front, have undergone rehabilitation, training, and employment. H.C. Corpening, director of Rehabilitation Services for Washington, stated that “increasing numbers of soldiers, sailors and Marines – disabled in action – are being placed in private industry for which they are best suited… The intensive industrial need for workers has stepped up the hiring of other employables in addition to the disabled veterans.” Safety devices keep the accident rate among these workers at a minimum.

At the Maryland League for Crippled Children, disabled women are hand-burring Y’s for airplane engines on subcontract to the White Engineering Company in Baltimore, Maryland. Photograph by Ann Rosener. From the Library of Congress.

Like these capable veterans, other amputees and people with physical impairments are active in war production and general, civilian work. Those with missing limbs work as welders, the paralyzed polish lenses for bombsights, one-eyed men work at engine lathes, and one-armed boys serve as water carriers on construction jobs or as messengers and clerks. In New York City alone, 40% of the placements of the handicapped by the Employment Service were in the metal trades.

Although people with disabilities are making gains in the workforce, some still face opposition.

In February of this year, Jerry Kluttz of the Washington Post recounted instances of disabled young women being denied jobs because of disabilities that in no way would have affected their job performance. “She’s a hopeless cripple,” a supervisor of the Federal Service said when one such woman applied for a typist job for which she was highly qualified. “We don’t want anyone who’s physically disabled in our organization.” This would-be typist suffers from polio. Ironically, President Roosevelt battles this same disability.

Although some employers discriminate against the disabled, others recognize that at a time when the turnover rate among workers is extremely high, requiring constant training of new workers, hiring the disabled offers a great advantage.

“Those partially disabled, but still able to perform certain mechanical duties, have attained a status practically preferential, in that they are exempt from potential military service,” Corpening told the Washington Post. Men who have disabilities are typically classified into Class IV-F, which means that they are not qualified for armed military service and are essentially “draft proof.”

Employment Service officials have also said to the Wall Street Journal that “a physical handicap need not mean less or poorer work.”

To stress unity in these pressing times, attendees of the “Wake Up America” rally held in April emphasized that Americans must “give up your old peacetime arguments and bickerings… If America lets this Commander in Chief down the enemy will appoint the next one.”

So for the blind jigsaw operator, the blind rivet sorters, the deaf women operating power sewing machines, and the millions of disabled Americans finding their niches in the war and civilian industries, the dissenters and doubters matter very little. It is evident that their contributions are crucial for sustaining home front morale and for ensuring an Allied victory.

As Burton Lindheim of the New York Times puts it, “the eagerness of the handicapped to join our production army demonstrates that patriotism is by no means confined to the able bodied.”

Sources:

“Blind Man As Masseur Typifies Upturn in Jobs For Physically Handicapped In War Centers.” The Wall Street Journal, May 6, 1942, p. 7.

“Blind Students Aid War.” Pittsburgh Courier, March 14, 1942, p. 23.

Kluttz, Jerry. “Case of Paralysis Victim Being Denied Job.” The Washington Post, February 2, 1942, p. 13.

Petersen, Anne. “Deaf and Blind Fill War Posts.” The New York Times, June 28, 1942, p. D4.

“Disabled in War.” The Guardian and The Observer, June 20, 1942, p. 8.

“Disabled Service Men Getting Many Jobs.” The Washington Post, February 18, 1942, p. 28.

Lindheim, Burton. “’Disabled’ War Workers.” The New York Times, May 31, 1942, p. SM29.

“Program Offered For Training Blind.” The New York Times, June 21, 1942, p. 29.

“To Aid Disabled In War.” The New York Times, July 9, 1942, p. 7.

“Veterans Back President.” The New York Times, May 1, 1942, p. 21.

Duffield, Eugene S. “Automatic Deferment Of Married Men to Be Effective in Few Days.” The Wall Street Journal, June 19, 1942, p. 1.