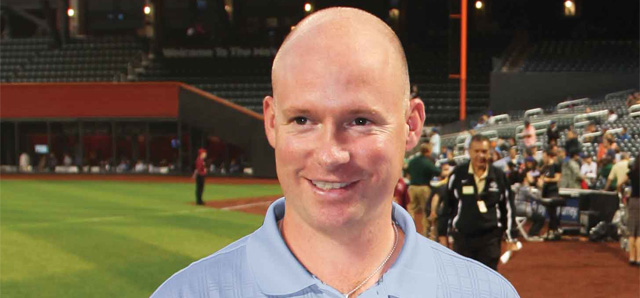

The way Coach Kevin Willard sees it, basketball imparts important lessons about life — on and off the court.

The way Coach Kevin Willard sees it, basketball imparts important lessons about life — on and off the court.

Kevin Willard’s ascent as a basketball coach has been both rapid and unusual.

Seton Hall’s new men’s coach, just 35, grew up in Northport, Long Island, the son of Ralph Willard, a high-school basketball coach who went on to fame as head coach at several universities, including Holy Cross, Western Kentucky and the University of Pittsburgh.

Coaching basketball, it seems, runs in the Willard family. Though nothing about Kevin’s coaching career was preordained, it may seem that way in retrospect.

“My first memories of childhood were being in St. Dominic High School’s gym, chasing down balls and helping [my Dad] varnish the floors,” he says. With his older brother Keith (“my best friend for as long as I can remember”), Willard would play hide-and-seek in the bleachers, take shots along the side of the court while the team practiced, and share a family pizza in the gym if the evening ran long. “It was a huge part of my family’s life, like going to all the away games.

It was what we did,” he says.

His father, now an associate coach at Louisville,

agrees, noting that Kevin’s mom, Dorothy, was a physical education teacher at St. Dominic’s and that Kevin’s younger sister, Pamela, acted as a combination mascot and cheerleader. “We always had the kids in the gym.

Our whole family lived around sports.”

That doesn’t mean the Willards were obsessed. “My Dad didn’t force basketball down my throat,” Willard emphasizes. “He never pushed the game on me. In fact, he didn’t seem to give a hoot if he saw me make a terrible layup.

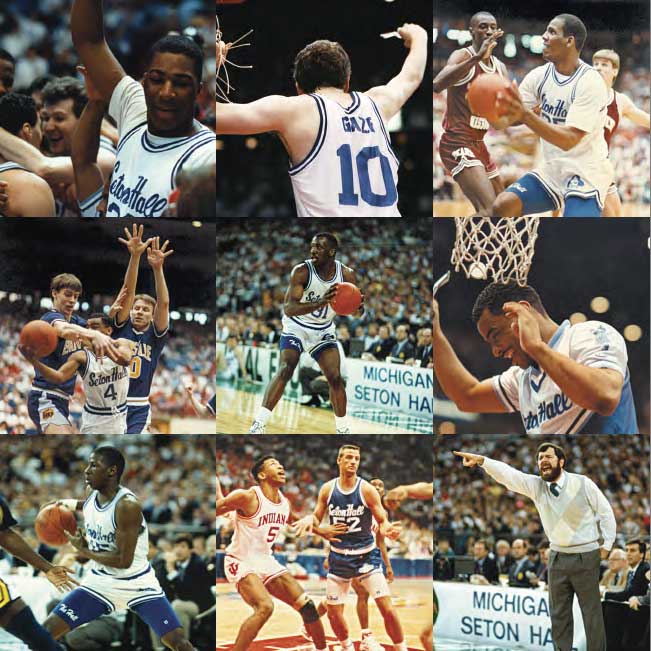

“I didn’t really start learning about my father as a coach until I began playing for him [at Western Kentucky],” Willard says, noting that his own focus was on becoming an NBA player.

“But it hit me at around age 19 that I wasn’t going to be the next John Stockton,” Willard says with a laugh, referring to the Utah Jazz great.

That’s when he started to look closely at how his father led young men to do their best. His first discovery: “I was amazed at the amount of respect they had for him. They always told me how much they enjoyed playing for my father.“

The lesson was “to treat players like men and expect a great deal from them.” Both Willards today seek to recruit young men who are not only great basketball players, but who also have potential off the court, Willard says.

How does a coach build that kind of life success? Several ways: “You give them great structure in their lives. You give them the responsibility of being prepared and on time. And you talk to them a lot about being sharp off the court.”

Basketball, Willard believes, is a microcosm for the human experience.

“It really does teach young men everything they need in life to be successful,” he says. And it does it in a pressure-cooker atmosphere. “Every time they step on the court, they are right in front of 15,000 fans who can see their every facial expression. They can see when things go bad and well.”

Some character development occurs outside the gym, as Willard knows from personal experience. “When Kevin was a freshman at Western Kentucky, he wasn’t playing much,” his father recalls, “but he wasn’t moping around, either. Every Monday, I’d want to start studying the films, but they’d be gone. I’d ask everybody, ‘Where the heck are they?’ And they’d say, ‘Check with Kevin.’

So I’d head to the dorms and there he’d be, watching them, telling me what we needed to do. That’s when I started to understand how passionate he was about the game.”

Later, while Willard was averaging 2.6 points a game at Pitt, family friend Rick Pitino offered him the job as an advance scout for the Boston Celtics.

“I jumped at the opportunity,” Willard says of the experience he describes now as the equivalent of getting a Ph.D. in coaching.

As Pitino later told the The Star-Ledger, “The thing that stuck out to me was how much the pro players liked him. All the great players loved Kev. They’d sit and talk together, but he would turn around and teach the pro guys and he was very comfortable doing that. That’s very unusual for a young man who was 22, 23, to interact with the pros like that. They had a lot of respect for him.”

Willard’s father notes that his son can motivate players when they’re down, yet also apply strict discipline when necessary. “Kevin can handle people, as well as X’s and O’s. He has always been attuned to people’s feelings.”

Willard calls his time with the Celtics “the greatest experience I could have had to become a coach.” Not only was it an advanced course, it was a concentrated one: the pros play about 100 games a season, instead of the 30 in college. But after four years with the Celtics, he was ready to start his own coaching career. The opportunity came as an assistant to Pitino at Louisville.

Eventually — with encouragement from both Pitino and his father — Willard made the jump to head coach at Iona in 2007. There, he led the Gaels to an overall record of 21-10 in the 2009-10 season.

Now that he’s at Seton Hall, basketball and family remain tightly entwined. After all, this season, the Pirates will play Louisville’s Cardinals, where his father is an associate coach for Pitino.

At home, Willard’s wife, Julie, and their two sons are big fans. “They’re already ball boys,” he says of Colin and Chase, who are 4 and 2.

But following another family tradition, he’s applying no pressure. “I also have a golf club in their hands,” he says.

Bob Gilbert is a freelance writer in Connecticut.