Why Women Haven’t Won: The Presidency and the Equal Rights Amendment

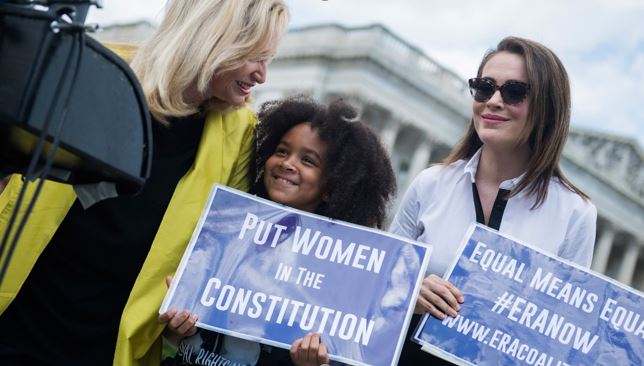

Photo credit: Tom Williams

By Becca Blaser

Due to the rampant spread of COVID-19, American politics have seemingly moved to the back burner—and rightfully so. However, it is difficult to ignore the reality that the country will experience another four years without a woman at the lead. Senators Elizabeth Warren and Amy Klobuchar and Representative Tulsi Gabbard were the last women standing after a record number of female candidates campaigned for the presidency, all on the Democratic Party ticket. Each suspended their campaigns after disappointing results in the primary elections and the realization they would not receive enough votes for the Democratic nomination. This realization begs the question: why didn’t any of these women receive enough votes?

This is a loaded question. Many say the American people are skeptical of electing a woman after Hillary Clinton’s failure to win in 2016. Others are concerned that “advancing the cause of women” is not as important as electing a male candidate that could defeat President Trump. One writer argues that those voting favored the familiar and the known, i.e. a candidate such as former Vice President Joe Biden who has been on the political stage for nearly half a century. Many women and men alike contend that this year was just not the time for a woman president. But why such skepticism? Why is the country not ready? When will the American people be ready? These are questions that preoccupy the thoughts of little girls and women everywhere – questions that cannot be answered without considering America’s history and the role women have played in it. Uncertainty towards the idea of a woman president still exists, and the failure to pass the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) may have something to do with it.

The Equal Rights Amendment was first proposed in 1923. However, it did not receive Senate approval until 1972, when the feminist movement was making important strides with efforts from activists like Gloria Steinem and lawyer (and future Supreme Court justice) Ruth Bader Ginsburg. At its core, the ERA is designed to ensure the equality of rights under law which cannot be denied or abridged on the basis of sex. The amendment was left to the states to ratify but failed to receive a majority of votes to put into practice. Much of the controversy surrounding the ERA—then and now—deals with the changing societal roles for men and women that the amendment would supposedly bring forth, such as compulsory military service for women.

No matter its controversy or its critics, the Equal Rights Amendment, on its face, seeks to provide equality for men and women under the law, something that is still not in place even today. Passing the ERA would send an important message to the American people that the government cares and the law strives to treat all people equally, no matter their gender. Even critics note the important symbolic and cultural value that its passing would represent. The failure to put this amendment into law in the 1970s or today continues to send the message that certain laws which benefit one gender over another are acceptable. Regardless of opinions that its passing may cause more harm than good, any amendment has its challenges and obstacles to overcome; these should not hinder its potential success. All people should have the same opportunities, no matter their gender, and the ERA would provide an institutional legal framework to ensure this.

This is not to say that if the Equal Rights Amendment passed or passes in the future, that a woman will win the presidency with ease and without obstacles. Women are considered ignorant if they do not acknowledge their “tougher political road,” yet are seen as weak if they do. Nevertheless, the historical scars placed on women cannot be ignored. It took fifty years for the ERA to gain serious consideration; once it finally did, female representation in government continued to remain relatively low. A woman did not receive a presidential nomination from a major political party until 2016. It is important to consider the deeper message that the law sends and the significance it holds. The revival of the ERA in recent months presents an opportunity to do right by women. “Every constitution in the world written since the year 1950… has the equivalent of an equal rights amendment, and we [the United States] don’t.” Interestingly enough, the United States is also one of the only major world powers that has not had a woman as head of government.

It is difficult for many to accept that American society and culture has changed. It is even more difficult for some to accept that women deserve opportunities that they should have always been afforded in the first place. Without any change, the law will continue to present challenges for women, be it unequal pay or pregnancy discrimination. As Justice Ginsberg said herself almost fifty years ago, continuing down the current path helps to “keep women not on a pedestal, but in a cage.” If the American people are truly ready for a woman to be president, it is time to enact the change—whether achieved through the Equal Rights Amendment or another avenue—that can help a woman get there.

Becca Blaser is a first-year MA candidate in Diplomacy and International Relations at Seton Hall University, specializing in Foreign Policy Analysis and International Law. This is her second semester working as an associate social editor for the Journal of Diplomacy and International Relations. Becca is a research assistant at the University and is part of the National Security Fellowship this semester. Her work has been published in International Policy Digest.

Becca, what a thought-provoking and fabulous article!! I look forward to reading more from you on many relevant topics today.