Rationality of North Korea Explained.

By Michael Hamilton

While many international relations scholars and policy-makers argue and assert that Kim Jong-un is acting rationally, President Donald Trump does not seem to agree. “Rocket Man,” as Trump affectionately calls him, has also been referred to Kim a “Madman” on occasion, while Kim has responded by calling him a “dotard.” The war of words has, perhaps reasonably, caused the American public to be concerned that war may occur. The United States has the world’s most powerful military, with a fully equipped fleet of aircraft carriers, stealth bombers, expensive fighter jets, a well-trained standing army, and most importantly a nuclear arsenal capable of triggering the end of the world.

For many, it seems insane for Kim Jong-un to be challenging this superpower, as North Korea is infamous for its famines, extreme poverty from an autarkic economic system, and has inferior conventional military capabilities. However, still, it continues to test missiles in open defiance of the “American imperialists” that threaten its sovereignty and security. The confirmation of a successful hydrogen bomb test and warhead miniaturization have changed the entire security dynamic of North East Asia. The window on preventative war seems to be gone, but it was never really an option to begin with. Simple game theory models, which international relations has a love-hate relationship with, show that the United States would be irrational if they went to war in response to North Korea’s ascendance as a nuclear power.

This security dilemma between North Korea and the United States is often described as a “game of chicken.” However, this depiction is inaccurate because of the sequential, or turn-based, nature of how events are unfolding. When examined sequentially, the chicken game shifts to another game called the “market entry game.” This depiction is more accurate not only because of its sequential nature, but because it also depicts North Korea’s attempt to enter the nuclear oligopoly. Only eight seven other countries are members of the nuclear weapons club, a club that North Korea, and possibly Iran, has put an immense amount of resources into joining. The P5 nations vehemently oppose this entrance as it violates the principles of non-nuclear proliferation, challenging their oligopoly of nuclear might. Despite the P5 protestations they cannot do anything to stop such development because of North Korea’s deterring position through both nuclear and non-nuclear means.

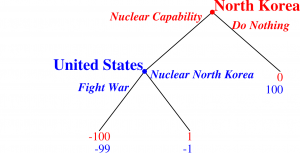

In the event of any decapitation strike or pre-emptive war operation, Pyongyang is set to rain massive artillery and ballistic missiles unto Seoul, which is well within range of a conventional attack that could obliterate the capital in as little as two hours. Although the United States has placed the THAAD missile defense system to detect and protect against such an attack, the accuracy of the system is disputed and does nothing to stop the artillery fire. In addition to these retaliatory military capabilities, a massive refugee crisis looms in the event of war. Lessons from the Syrian civil war show the difficulty in managing refugees fleeing war zones, which is a scenario no country in the region desires, nor is prepared for. Lastly, in a suicide attempt, North Korea could start a nuclear war by unleashing all of its nuclear capacity in a last-ditch effort to prevent regime collapse. These factors are key in framing this new age brinkmanship into a market entry game which shown below:

The payoffs correspond to the expected utility of outcomes due to strategic considerations of North Korea and the United States respectively. If North Korea does not develop nuclear weapons, the United States could easily obliterate the peninsular state with its advanced military, represented by the 100 payoff in that outcome. But if it develops a nuclear capability, the United States must now make a choice of whether to fight a war or accept North Korea as a nuclear power. Through backwards induction, we can show that North Korea is indeed rational by finding this game’s subgame perfect equilibrium (explained in the previous hyperlink). The United States and North Korea both have massive losses in utility if they fight a war. North Korea and its government would be no more in the event of war, represented by the -100 payoff.

However, the United States would also suffer sever negative payoffs from a regional war as well. The -99 payoff represents a loss in trading capability with South Korea, create a massive refugee crisis, and deteriorate its relations with Japan and China, who could possibly be victims of North Korean retaliation in addition to nuclear war. Because an attack on U.S. soil is unlikely because of the missile’s range, the -99 we assign a -1 payoff difference between the two states (this follows a value function described by Nobel prize winner Daniel Khaneman in Prospect Theory). If the United States does not fight such a war, North Korea gains the deterrence it so desires, while the United States loses hegemonic power in North East Asia.

Although the United States’ loses some utility in both outcomes, the relative losses are significantly less to the war outcome than if it chooses to not fight a war, as -1>-100. This makes the decision to accept North Korea as a nuclear state a rational choice, as a subgame perfect equilibrium, for the United States. Therefore, North Korea is also rational by developing nuclear weapons because it knows that the United States cannot stop it from doing because they both suffer severe losses from military retaliation, a refugee crisis, or a worst case scenario of a suicide detonation of its nuclear arsenal. The risks are indeed too great for the United States to engage in warfare if one is to follow the rational actor assumptions of international relations.

Although we have shown that North Korea is rational, and going to war is irrational for the United States, it is still a real possibility. President Trump doubled down on his military options approach by tweeting to Secretary of State Rex Tillerson to stop seeking negotiation channels. It is wise to heed the life lesson of former Defense Secretary Robert S. McNamara who insisted that “rationality will not save us.” While President Trump may believe negotiations are irrational choice he is misguided. Instead the lesson of McNamara should be considered, as negotiations are the true solution to this dilemma, while still maintaining deterrence and missile defense options as insurance in case of nuclear miscalculation.

Michael Hamilton is a dual degree student pursuing a Master’s in Business Administration and Master’s in Diplomacy and International Relations. He specializes in Game Theory and decision science, and is a supporter of global citizenship.

Follow the Journal of Diplomacy on Twitter at @JournalofDiplo