The US Needs More Bilateral Climate Agreements

Climate change is no longer merely an environmental problem; it has become a serious national security concern. Climate change increases the frequency of extreme weather events, displaces populations, affects food production, impacts disease vectors, and more. That climate change is a security issue has become undeniable, and is evidenced through the president’s 2015 National Security Strategy, as well as the Department of Defense’s 2014 Quadrennial Defense Review. Despite the fact that the US has very quickly made major strides in recognizing the importance and urgency of climate change, it has still failed to develop an effective strategy for dealing with climate change as a security issue on the same level as other security concerns. It is a security concern that is too important to merely hope that nations globally will come together and uphold a climate agreement.

Even though the US has acknowledged that climate change is real and presents a serious risk to our national interests, its place in foreign policy continues to be that of a secondary issue. Topics such as the conflict in Ukraine, or how to combat ISIS continue to dominate US foreign policy discussions even though climate change presents a more serious and pressing risk. If the US truly wants to avoid the most serious consequences of climate change, then it needs to begin treating it as a security issue. In the past, the US’ approach to climate change has been to avoid commitments, not wanting to constrain itself if potential rivals such as China are also avoiding commitments. The problem with this relativistic approach though is that it fails to avoid the high absolute costs of climate change, since developing nations such as China and India still have avoided making any hard commitments. Even Barack Obama, the US’ most environmentally progressive president, refused to sign the Kyoto Protocol in 2011.

The problem with this approach is twofold. One is that states have a high incentive to defect, free-ride, or lie about their commitments. Since climate change is a global issue, the state which does the least gets the most relative gain. The second issue is that climate change is a classic issue of value of compliance, or least common denominator. In order to get such a large number of states to agree to one agreement, it means that the agreement must be ambiguous as well as appeasing. The more nations involved in an agreement, the less convergence of interests among parties there will be. These problems are inherent to any large multilateral agreement, and are exasperated with climate change.

The solution to avoid these two problems inherent in a multilateral approach is to pursue bilateral agreements. If the US can use itself as a hub of bilateral agreements, it can tie climate change as a policy issue into other agreements, such as ones that are focused on energy or economics. We already see this approach to climate diplomacy in its infancy, with Obama’s November agreement with China, as well as the fact that climate change was a serious issue on the agenda for Obama’s visit to India, discussing nuclear energy.

Taking a proactive approach to climate change where the US makes its own agreements is a better approach than waiting for the rest of the world to come to some sort of consensus and somehow stick to it. It allows the US to target the most important big emitters, and elicit the concessions that it wants. It also has the benefit of being able to enforce time constraints that are of value to us. In the past finding a common time frame for agreements has been an issue; bilateral agreements allow the US to set time frames that are achievable and variable from state to state. The US has an opportunity to establish itself as a leader and create a climate regime that is to its choosing, but if it continues to take a hands-off approach then it is doubtful that it will ever achieve its climate change targets.

By Philip Rossetti

Philip Rossetti is a graduate of the University of New Mexico, as well as a scholar of the National Security Studies Program. He is currently pursuing a Master’s degree in Diplomacy and International Relations at Seton Hall University.

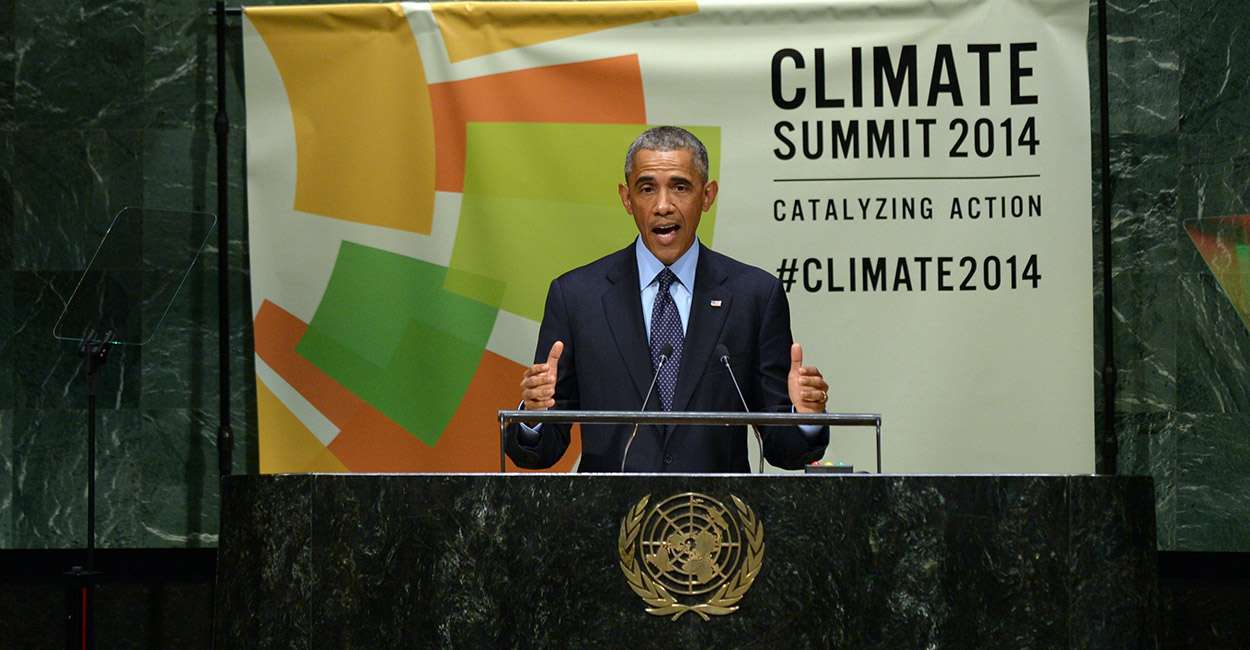

Featured image: Source