Rosie the Riveter is an iconic piece of art that started as World War II propaganda and is still to this day recognized as a feminist symbol for gender equality. World War II was a war of ideologies, with Fascism quickly emerging in Germany and Italy, other countries like England and France felt as though they needed to intervene. Fascism is an authoritarian, nationalistic ideology which believes in group superiority and justifies hate for a group that is perceived to be the enemy. Therefore when Germany’s ruler, Hitler, started to seize surrounding countries, and persecute his enemies (mostly Jewish people), the Allied powers had to intervene, which was made up of Great Britain, France, China, and the Soviet Union. Japan joined Germany and Italy because Japan wanted to control China and the Pacific for resources. The United States controlled part of the Pacific and when they cut off some resources to Japan, it triggered Japan to respond with violence. In 1941, Japan bombed an American Fleet at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, resulting in the United States entering World War II as an Allied power despite efforts to stay neutral and maintain isolationism. [1]

The Library of Congress – Operating a hand drill at Vultee-Nashville, woman is working on a “Vengeance” dive bomber, Tennessee

When the United States entered World War II, the entire social dynamic of traditional American Society had to change. With millions of men volunteering or being drafted to the War and hence leaving the work force, there left the problem of who would fill their jobs Ibid.,2. Women at the time were still expected to maintain the home and working was seen as taboo to many, even employers. However, despite the expectations and strict gender roles present at the time, it was not entirely uncommon to find women in the work force, especially single women, and women of color. Therefore, with the massive labor shortage, social norms had to revolutionize and encourage women to take jobs they would have never before Ibid.,3. Society viewed women as frail which is why many male employers thought they could not handle the labor-intensive jobs, but this narrative had to change in order to supplement the men that occupied those jobs.

Norman Rockwell’s Saturday Evening Post, 1943 cover featuring Rosie the Riveter

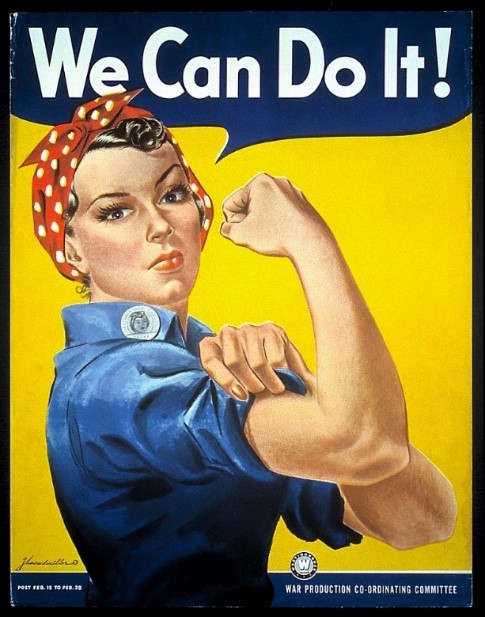

The United States government had to convince some women to join the labor force and they did this by releasing a series of empowering women propaganda, including Rosie the Riveter. Rosie the Riveter was created by an artist named J. Howard Miller in 1942 and was distributed by the War Production Coordinating Committee[2], originally in order to reduce absenteeism or missing work, and strikes at the Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company. Despite the fact that Rosie the Riveter was never meant to be widely distributed and idolized, years after her creation Rosie became one of the most recognizable gender-equality images. Miller’s iconic painting of Rosie the Riveter that the American publican has come to know and love actually is not the only version of this feminist symbol. Artist Norman Rockwell in 1943 actually made the name “Rosie the Riveter,” famous because his version of Rosie was published in The Saturday Evening Post on May 29th, 1943. Rockwell was a much more famous artist than Miller at the time, so his work and the “Rosie” name received a lot of attention. Rosie became so popular that a song was made by Redd Evans and John Jacob Loeb called “Rosie the Riveter,” just later that year. The “Rosie the Riveter” name became a feminist symbol and when the “We Can Do It!” poster started to gain publicity and the Rosie name began to be identified with it. Now Miller’s version of Rosie the Riveter is the most well-known and recognizable version of “her.”[3]

Women workers install fixtures and assemblies to a tail fuselage section of a B-17 bomber at the Douglas Aircraft Company plant, Long Beach, Calif.

Even though Miller’s original intent when creating Rosie, the Riveter was not women empowerment, soon thereafter Rose the Riveter became one of the most recognizable feminist icons in U.S. history. Alves writes, “The iconic images of Rosie the Riveter explicitly aimed to change public opinion about women’s work. Rosie encouraged women to apply for industrial jobs they may not have previously considered and aimed to make women’s industrial employment more acceptable to the public.” [4]The image specifically portrayed Rosie to have manly features like bigger arms, and her hair pulled back, all while maintaining some femininity by wearing makeup. The manly features were to empower women to feel strong enough to join labor-intensive jobs traditionally carried by men. Miller using the iconic, “We Can Do It!” phrase further emboldened women to break out of their strict gender roles by giving them the confidence that they can do traditionally male jobs. Santana writes, “The war posters and magazine ads of the time reinforced the duty women had toward the war effort. Although women at the time were mostly occupying the private space, the war campaign of Rosie the Riveter inspired many of them to take their work to the public.” [5] This quote further proves how impactful the imagery of Rosie the Riveter was for women at the time.

Although Rosie the Riveter and other feminist wartime propaganda, had positive effects on female moral, they, unfortunately, have patriarchal roots. The intention of the propaganda put out during this time was to get women into the labor force for wartime and once all the men came home, they would be okay going back to their traditional gender roles of being a house wife. In her book, “Creating Rosie the Riveter: Class, Gender, and Propaganda During World War II,” Maureen Honey exposes this reality. In the 1940s many people held conservative values which are reflected by the fact that the true intention of “feminist” wartime propaganda was to not change gender roles in the workforce for the long term. Capitalists simply wanted

Bruce Plante, Rosie the Nurse, March 22, 20202, Bruce Plante Cartoon, acessed December 5, 2020 https://tulsaworld.com/opinion/columnists/bruce-plante-cartoon-rosie-the-nurse/article_30b911b1-c4e9-5479-8737-7f6dd6bc0534.html

women to fill men’s jobs for the duration of the war and return to the home or their low paying secretary job.[6] Honey writes, “women were manipulated by the media into false consciousness of their roles as workers, both contend that tying war work to traditional female images was a logical direction for capitalist ideology to take because it reinforced women’s inferior position in the work force at a time when material conditions challenged sexist work divisions.” Ibid, 2. What Honey’s analysis exposes is that the original intention of the Rosie the Riveter icon was not entirely to empower women, but only empower them enough to do men’s work while their gone and then retreat back to a housewife-like life post World War II. Although that was the intention, we now know how truly impactful Rosie the Riveter has been for feminist movements and for closing the gap of gender inequality. Even though, there is still clear sexism within our society, it is arguable that without Rosie the Riveter and other war campaigns for women, that we would not be nearly as socially progressed today as women in society.

[1] David Emory Shi, America: A Narrative History Brief 11th Edition, Vol. 2 (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, INC.,2019) 1055-1076

[2] “We Can Do It!” National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_538122 , accessed November 1st, 2020

[3] Sarah Pruitt. “Uncovering the Secret Identity of Rosie the Riveter,” History.com, last modified, March 26th, 2020 https://www.history.com/news/rosie-the-riveter-inspiration#:~:text=During%20the%20war%2C%20Miller’s%20poster,more%20famous%20artist%3A%20Norman%20Rockwell.&text=The%20woman’s%20lunch%20box%20reads,Evans%20and%20John%20Jacob%20Loeb. Accessed December 3rd, 2020

[4] Andre Alves and Even Roberts. “Rosie the Riveter’s Job Market: Advertising for Women Workers in World War II Los Angeles.” Labor (Durh), vol. 9, (Fall, 2012) 53-58. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5648367/ , accessed November 1st, 2020

[5] María Cristina Santana. “From Empowerment to Domesticity: The Case of Rosie the Riveter and the WWII Campaign.” Frontier in Sociology: Gender, Sex, Sexualities, vol.1, (December 2016): 1-16. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsoc.2016.00016/full#h10 , accessed November 1st, 2020

[6] Maureen Honey. Creating Rosie the Riveter: Class, Gender, and Propaganda During World War II. Vol. 2nd print., with revisions. (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1985) https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=sso&db=nlebk&AN=13848&site=ehost-live., accessed November 1st, 2020