Private Credit Warning After Recent Collapses

Ethan DiGiacomo

Staff Writer

Just weeks before its bankruptcy, First Brands Group was being pitched to investors as a $6 billion loan opportunity. Jefferies Investment Bank was marketing the deal. The company was said to have nearly $1 billion in cash. Tricolor Holdings collapsed even faster. Tricolor operated as both a used car dealership and a subprime lender, offering high-interest loans to borrowers with limited or no credit history. It packaged those loans into AAA-rated securities and sold them to investors. When repayments faltered, the whole structure unraveled. Fifth Third Bank, one of its creditors, is accusing Tricolor of fraud, alleging that the company pledged the same assets as collateral for multiple loans. Investigators are now combing through what may be a corrupted loan database, and banks have begun repossessing vehicles from dealership lots. The speed of these collapses caught investors off guard. Just months ago, First Brands’ debt was marked at full value by private credit funds; some even marked it above 100 cents on the dollar. Tricolor’s AAA-rated securities were trading at full value before the bankruptcy.

Today, however, First Brands’ top loans are worth only about one-third of their original value, and Tricolor’s lower-level bonds have crashed to just 12 cents on the dollar. These weren’t supposed to be crazy investments. They sat in the portfolios of pension funds, insurers, and asset managers, institutions that aim to avoid volatility, not absorb it. Kroll, a bond rating agency, cut its bond rating on some Tricolor bonds from AAA to CC. These defaults have exposed weaknesses in the credit markets, leading investors to question lending standards and the structure of private debt markets. They’ve also raised questions about how much risk is hiding in supposedly safe securities and whether there are more future surprises.

Divisions in America’s Economy

The US consumer economy appears to be dividing. Wealthier American households are feeling quite rich. Many bought homes before the pandemic with low-interest-rate loans, and house prices are now up significantly. This class is also being helped by their investments, with the stock market at near all-time highs. Poorer households are only getting poorer. Persistent inflation has pushed up the cost of everyday essentials. Interest rates on poorer Americans’ loans are high, and things like used car prices are still high relative to pre-pandemic levels. Other expenses like insurance premiums and car maintenance costs, which make up a larger percentage of low-income Americans’ spending, have outpaced headline inflation. According to Fitch Ratings, a credit rating agency, 6.6% of subprime auto loans are at least 60 days past due. This is the highest level seen since the agency began collecting data on them. Credit card defaults and student loan defaults have also risen sharply.

Tricolor’s collapse reflects some of this pressure. The company specialized in lending to borrowers with limited access to traditional credit. Many were undocumented workers who lived paycheck to paycheck. Some analysts have pointed to immigration enforcement as a contributing factor. Deportation fears and labor force exits may have disrupted repayment patterns, though the extent of the impact remains unclear. First Brands was exposed to a similar consumer base, but indirectly. Its parts were sold through retailers that cater to budget-conscious drivers. The problem may not be the customer base but the capital structure of the business. First Brands had borrowed heavily to fund acquisitions, then borrowed again against invoices and inventory. Rising tariffs added further strain to their business model, increasing costs on imported components and squeezing margins. There are other signs of general weaknesses in the business sector. Sales of semi-trucks, which can indicate to investors how busy businesses expect to be in the coming months and years, have fallen 24% since May 2023, the lowest level seen in five years. Labor market data adds another layer of uncertainty. ADP’s private payroll report showed a loss of 32,000 jobs in the most recent period. Unemployment affects credit markets both as a leading indicator and as a trigger. When jobs disappear, repayment risk rises.

The Problem with Private Credit

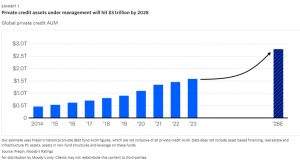

The collapse of these companies has drawn attention to the nearly two trillion-dollar private credit market that has fueled Wall Street’s recent boom. Policymakers have spent the past decade shifting risk away from banks and into the hands of non-bank lenders. That strategy will have reduced systemic exposure, but it’s also made it harder to track where the pressure in the economy is building. Private credit ballooned when banks, faced with higher regulation, withdrew from riskier lending in the wake of the global financial crisis. These new private lenders sought to capture high returns and were willing to put up with the risk involved. This has led to extraordinarily complex financial arrangements, many beyond the sight of regulators and even the institutions involved. Private credit was supposed to be smarter. Lenders wrote bespoke contracts, contracts tailored to each borrower. They avoided public disclosures, sidestepped mark-to-market volatility, reporting an asset or liability at it’s current price rather than the original cost, and operated in relationships that promised flexibility in a downturn.

The model was pitched as safer than bank lending and more disciplined than public debt markets. First Brands showed how that model can break. The company had multiple layers of financing, some syndicated, some private, and some off-balance sheet. Lenders didn’t have a full picture of the overall capital structure. Some may have discovered they were exposed to collateral that had been pledged more than once. The fallout from First Brands and Tricolor has reached deep into Wall Street. Jefferies now faces reputational damage. Its investment unit was also exposed to the company’s invoice financing, an arrangement that may not have been adequately disclosed to other lenders. Millennium Management, one of the world’s largest hedge funds, is among those facing losses. Tricolor’s collapse has hit banks directly. JPMorgan, Barclays, and Fifth Third Bank provided lines of credit to the company, expecting to be repaid once the auto loans were securitized. That repayment never came. Bondholders are now scrambling to protect their claims. Clear Haven Capital has been calling other investors, urging them to coordinate legal strategies. Auditors are also under scrutiny. BDO gave First Brands a clean audit earlier this year, and the company collapsed just months later, revealing a $12 billion web of liabilities. Deloitte was hired to produce a quality-of-earnings report, but the bankruptcy beat them to it. Some investors saw the trouble coming. Apollo Global Management and Diameter Capital shorted First Brands’ debt before the collapse.

Private credit is often described as being outside the banking system. That’s not quite true. Non-bank lenders, private credit funds, hedge funds, and specialist finance firms borrow from banks. They rely on revolving credit lines and bridge loans. Bank lending to non-bank financial institutions (NBFI) has surged. It now accounts for all of the growth in bank lending this year. One regional bank reportedly has $62 billion in loans to shadow lenders, 1/5 of its loan book. Most of it is categorized as “business,” “private equity,” or “other.” The risk isn’t just that these lenders might fail. A non-bank financial institution under pressure is most likely to tap its bank credit just as the value of its collateral is falling. Regulators can see the exposures, but investors can’t. Quarterly filings don’t break out NBFI lending in useful ways. Wall Street doesn’t seem rattled. The leveraged buyout of Electronic Arts, a gaming company with flat revenue, was announced just days after First Brands collapsed. The deal, valued at $55 billion, is the biggest leveraged buyout in history. The deal includes twenty billion dollars in debt. If there’s fear in the private credit market, it’s not showing up in the deal flow. There’s no sign of a crisis, but there’s no sign of caution either.

The Shaky Future of Private Credit

Credit markets aren’t melting down, but they are not really compensating investors for the risks they’re taking either. First Brands and Tricolor are not systemically important, and their failures didn’t trigger a panic. But they possibly reveal how fragile some corners of the credit market have become, especially when leverage becomes murky. These weren’t unique instruments held by speculative traders. They were AAA-rated securities, backed by collateral, sold to institutions that prize stability. The structure of risk has changed a lot since the global financial crisis. Much of today’s subprime and corporate debt sits with investment managers, insurers, pension funds, and entities funded by longer-term liabilities. That’s a lot different from the asset-backed commercial paper and bank deposits that once helped cause the last crisis. But the funding model isn’t the only variable worth watching. Private credit has grown rapidly, and so has its reliance on bank financing. Shadow banks now account for all of the growth in U.S. bank lending this year. At $1.7 trillion, shadow bank lending now represents 13% of total bank loans. There’s no sign of fear in markets, other than the dollar being down about 10% year to date. Credit spreads are tight. Equity markets are buoyant, and the largest LBO in history was announced just days after First Brands collapsed. If investors are worried, they’re certainly not showing it. But the question isn’t whether the market will unravel; it’s whether investors are being adequately compensated to take the risks they’re assuming. When spreads are thin and structures are unclear, even a stable system can produce nasty surprises.

Contact Ethan at ethan.digiacomo@student.shu.edu