Argentina’s Twin Deficits and the Peso Crisis: Milei’s Reforms Amid IMF and U.S. Bailouts

Ethan DiGiacommo

Staff Writer

In recent days, Argentina’s economy has made international news. On September 22, Argentina’s economy dropped 10%, and its currency, the Argentine peso, has lost 99% of its value over the past decade. Argentina is staring down another wave of financial turmoil, with the peso once again at the center of the storm. On the same day, investors pulled money out at such a pace that the government had to spend nearly 700 million dollars in a single day to stop the currency from breaking apart. That scale of intervention on top of America’s bailout shows just how close the country is to tipping back into crisis. The peso does not trade freely like the dollar or the euro. Instead, it sits inside a tight range that was set with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) as part of a 20-billion-dollar loan deal. This, coupled with the recent U.S. bailout worth another $20 billion, is meant to buy stability while President Javier Milei carries out his reform agenda.

Argentina’s Problem

Argentina’s economy is diverse but heavily reliant on agriculture and natural resources, contributing about 15% of GDP, with key exports like soybeans, corn, and beef driving over 60% of export revenue ($34.7 billion in 2024). Argentina runs a large trade surplus, even when adjusting for its current currency collapse, they are still at a near-record-high exports. Services, including finance and tourism, account for 60% of GDP, with manufacturing, food processing, autos, and mining making up the remaining 25%. Despite its healthy trade surplus, primary income is heavily dragged down by a massive amount of external debt. About $400 billion worth of debt, with annual interest often exceeding $10-15 billion. Foreign governments, individuals, or banks own that debt, so Argentina must be sending money for interest payments out of its country. Because of the foreign debt, the current account reflects the economic situation much better than the trade balance, which indicates that Argentina is economically healthy with a good trade surplus. A current account records the value of exports and imports of both goods and services and international transfers of capital from a country. Despite the trade surplus, Argentina runs a current account deficit, more capital is leaving the country than coming in. Most of that capital is being used to pay off the debt and interest on the debt.

To make matters worse, they have also run a very large government budget deficit or fiscal deficit, meaning the government has spent more money than is collected in tax revenue. At its worst in 2020, the Argentine fiscal deficit reached 8.3% of GDP. In comparison, the U.S. has a 7% GDP deficit. Many think this can be fixed by raising taxes, but in Argentina it did not work. The income tax and sales tax have stayed constant since 2013, but the government did raise the corporate tax rate in 2021, from 30 to 35%. Yet in dollar terms, their revenue has gone down. At the same time, revenue as a share of GDP from the time that they hiked taxes went from 31% of GDP, which is good, to just 17% of GDP, and it killed real GDP growth. That is the problem with heavily indebted governments. Taxes constrain growth, which hurts revenue and makes the deficit worse.

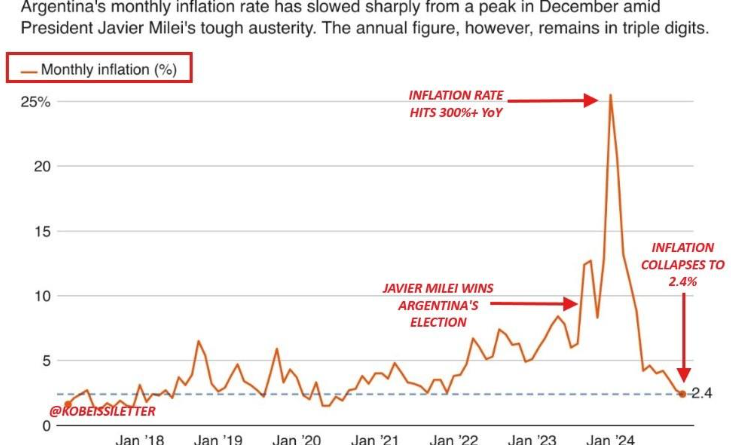

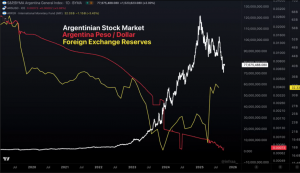

Argentina’s twin deficit of both a current account deficit since 2008 and a fiscal deficit, continues to be a problem. However, they have been able to turn around the fiscal side. In 2024, Milei was able to achieve a 1.76 trillion-peso surplus, the first surplus in 14 years, but adjusted for the failing currency, looking at the surplus in terms of USD or GDP, it is only a 10-billion-peso surplus. As of now, Argentina has a 1.8% surplus of GDP. Argentina has also been struggling with hyperinflation. In the U.S., the overnight interest rate for the Federal Reserve is about 4%. Argentina’s overnight interest rate is about 45%, and its annual inflation in 2024 was running at 292% per year. At its peak in the late 80s, the annual inflation rate was more than 4000%. They have had a bout of disinflation, meaning the rate of inflation has come down to just 39%. Milei has had some success with GDP and growth. Looking as recently as November of 2024, GDP was close to 0%. The economy was not growing or contracting; it was stagnant. Now Argentina has a 6.4% GDP growth, meaning its economy is growing at twice the rate of the U.S. Unemployment has been ticking up for them; 7.6% is their most recent headline unemployment rate. This is up from 5.5% when Milei took office, and it’s worse for certain populations like the youth.

Argentina’s Savior?

Milei’s plan to help Argentina’s economy is centered on drastic free-market reforms designed to stabilize the currency, curb inflation, and reduce the size of government. His plan has large spending cuts, including the elimination of subsidies for utilities and transportation, and downsizing the public sector by cutting ministries and freezing many public works. Alongside austerity, Milei has launched sweeping deregulation, rolling back price controls, loosening labor laws, and opening markets to foreign investment and trade. He also intends to privatize state-owned companies and has proposed abolishing the Central Bank, moving toward dollarization, or at least allowing free competition of currencies, which he believes will break Argentina’s cycle of inflation. Since taking office, he has already devalued the peso, cut subsidies, and implemented hundreds of regulatory reforms in what he calls a shock therapy approach. The goal is to balance the budget, rebuild investor confidence, stabilize the exchange rate, and eventually bring down inflation while making Argentina more competitive globally.

So far, Milei’s economic plan has shown some early signs of success, specifically with disinflation, the first budget surplus in years, and growth as mentioned earlier, but the results remain fragile. The plan comes with steep social costs. Many Argentinians are struggling with rising prices for food, rent, and services that still outpace incomes, while subsidy cuts, layoffs, and wage freezes have hit the poor especially hard. At the same time, Argentina’s currency and reserves remain vulnerable, and the political backlash to Milei’s shock therapy is strong. Milei’s party lost a significant number of seats in a local election recently. This has boosted fears that the kind of profligate spending, large deficits, and irresponsible money printing that had plagued Argentina for so many years will return. As a result, there has been a sell-off in the stock market (about a 40% drop in the week leading up to the proposed stock market), a sell-off in the currency (the currency has been moving lower regardless), and a sell-off in the dollar-denominated bonds.

Why Argentina is Getting Bailed Out

Argentina’s economy has gotten so bad that the U.S. Treasury Department has decided to step in. On September 22, US Treasury Secretary Bessent posted on X that “all options for stabilization are on the table” for Argentina. This may include swap lines, direct currency purchases, and purchases of USD-denominated government debt. Why would America care about a seemingly random South American economy? It’s ostensibly a chess move in America’s war with China. China is now one of Argentina’s largest trading partners, with trade between the two countries surpassing $20 billion in recent years. Argentina primarily exports agricultural products such as soybeans, as well as lithium and other resources, while importing a wide range of manufactured goods from China, resulting in a consistent trade imbalance. Cooperation extends beyond trade, with China investing heavily in Argentine infrastructure, renewable energy, and mining projects, particularly in lithium, while Argentina formally joined the Belt and Road Initiative in 2022 to deepen economic and connectivity ties. Financially, the two countries maintain a currency swap agreement that has allowed Argentina to bolster reserves and even repay IMF obligations, and trade settlements in yuan are becoming more common as Argentina seeks alternatives to reliance on the U.S. dollar. By helping Argentina, the U.S. is hoping to influence Argentina from moving away from working with China. President Milei is already more pro West than his predecessor, as he removed Argentina from its plan to enter BRICS when he was elected in 2023.

If Argentina’s economy has had problems for a while, why does it need a bailout now? Immediately after Javier Milei became Argentina’s president, inflation hit over 300%. In late 2023, inflation in Argentina was above 25% per month. At one point, a cup of coffee cost more by the time it was drunk. While it has dropped to 39%, this is not sustainable. And the recent increased acceleration of the Argentine peso collapse has not helped. Milei has lost the confidence of investors. In a final attempt to save the peso, Milei’s central bank injected $1 billion in 3 days. Intervention hit $1.1 billion, a massive amount in a country that has $20 billion in liquid foreign reserves. As of September 18th, Argentina’s debt is back in distressed territory. Argentina’s stock market has become the worst performer among more than 90 global benchmarks this month.

The effects have been socioeconomically catastrophic for the Argentinian people. Currently, over 38% of Argentines are living in poverty. In 2024, the country saw a poverty rate that was as high as 52.9%. The majority of Argentina’s population was living in poverty last year. On April 11th, Argentina attempted a lifeline with the IMF. The deal included a $20 billion agreement with the IMF, which included a $12 billion upfront payment. One of the requirements is that Argentina’s central bank will allow the peso to trade freely in a range of 1,000 to 1,400 pesos per dollar. However, this clearly has not fixed the issue. At its core, the Argentine peso is overvalued and artificially propped up by the government. Short-term relief by the IMF or the US will not fix the long-term issue. The Peso needs to trade freely without government manipulation. But now the peso is pressed against the top of that range, around 1,475 per dollar, and even slipped past it. That is a warning sign, because once the peso breaks through and the government cannot hold it, a rapid devaluation and another burst of inflation could follow.

The Bailout

On September 24, Scott Bessent announced on X that a bailout deal had been decided. Part of the deal includes the U.S preparing to buy Argentine sovereign debt and inject direct liquidity into the system. Standby credit facilities are also on deck, designed to keep Argentina solvent while securing American influence. One of the biggest parts of the deal is the $20 billion swap line. What is a swap line? A swap line is an agreement between two governments that allows them to exchange or swap one currency for another. For example, the U.S. has permanent standing swap lines with close allies like the banks of Canada, Japan, and England. But the U.S. does not have a standing swap line with Argentina. It’s important to point out from a geopolitical standpoint that Argentina does have a $5 billion swap line with China.

If the US is trying to gain influence, giving a swap line four times larger than China would be a good way to do that. A swap line is temporary, usually under 90 days, and with interest depending on whatever the overnight interest rate is, plus a spread, usually a small spread of half a basis point. Dollars are printed electronically, similar to quantitative easing. The Fed increases its liability, which is the dollar deposit, and then assets are also increased by a similar amount because one currency is being exchanged for another. The Fed credits, in this case, $20 billion to the Argentinian central bank, and it’s sent electronically. The Argentinian central bank now has $20 billion it didn’t have yesterday. The Argentinian central bank sends the equivalent of whatever the exchange rate is to the Fed, in this case, based on the current exchange rate, 26.4 trillion pesos. Argentina now has $20 billion to use for domestic liquidity needs. And the Fed has Argentinian pesos as collateral for the term of the swap. At the end of the term, usually about 3 months later or within 3 months, the Argentinian central bank will repay the U.S. $20 billion U.S. plus interest, and the Fed sends the 26.4 trillion pesos back to Argentina. There is no foreign exchange currency risk for the Federal Reserve because defaults are rare.

The other part of the bailout is using the Exchange Stabilization Fund (ESF). Looking at the balance sheet for the ESF, the total net position is about $219 billion. The ESF is a reserve fund, but it acts like a slush fund for the US Treasury that doesn’t have much oversight. It’s a pool of assets like dollars or foreign currencies. It is controlled by the US Treasury Secretary, and it’s meant to stabilize the US dollar in global foreign exchange (forex) markets. It can also provide short-term aid to foreign countries or intervene in other countries’ currency crises, like in Argentina. It can buy or sell foreign currencies, which is, forex intervention. The U.S. could extend a dollar loan to the Argentinian government. It would come out of the ESF, or we could purchase foreign bonds. From the ESF, dollar-denominated bonds could be bought, which would boost the bond value and decrease the interest rate. Anything for a foreign loan over $5 billion or for a long-term basis does need presidential approval.

There’s no annual budget from Congress. Earnings that the ESF accumulates are from holding treasuries, holding foreign bonds, and holding currencies via interest or forex gain. If the currency is strengthening versus the dollar, that would be a gain for the ESF. Short-term borrowing from the Fed can be done via the ESF by issuing special notes that are not interest-bearing. Transactions are balance sheet adjustments; no actual new money is being printed. This works when the Treasury Secretary decides to purchase some Argentinian dollar-denominated bonds. The ESF then uses existing US dollar cash holdings. These would come from pasvt profits. For example, in the 1930s, when gold was revalued, that gain was captured via the ESF. If the ESF owns foreign bonds, it is receiving interest, which is another gain for the ESF, and also returns from prior operations. If there aren’t enough dollars sitting in the ESF, it could sell some of the foreign currencies or treasury bonds that it has. Argentina is short on dollars because it needs to pay off its dollar-denominated debt. Well, what happens when the dollar goes vertical against its own currency? They get short squeezed. When the ESF goes to purchase these dollar-denominated bonds, that will put downward pressure on the interest rate and ease the burden for Argentina. It creates upward pressure on the value of the bond. For example, the 4-year bond is trading up at 60 cents when just a couple of days before the bailout, it was trading at 50 cents on the dollar. That means interest rates have come down.

The Argentine peso and thus the Argentine economy is under heavy strain for multiple reasons. Argentina is running short on dollars, which it needs for imports and debt payments. Tourism has slowed, farm exports have dropped after tax breaks were rolled back, and the trade deficit is widening. Inflation has stayed extremely high above 180% earlier this year, eroding savings and weakening the peso further. That leaves both Argentines and investors scrambling for dollars, which drains the central bank’s reserves and adds even more pressure.

The political backdrop is making things worse. Milei came in at the end of 2023 promising bold cuts and reforms, and at first, markets responded positively. Inflation cooled slightly, and there was hope the economy might turn a corner. But his party has since lost local elections, austerity has fueled public anger, and corruption scandals close to his circle have dented trust. Confidence in his ability to deliver has started to unravel. The central bank has been forced to sell hundreds of millions of dollars almost every day to defend the peso’s band. Reserves were already thin, and analysts say it could take up to 10 billion dollars to keep the peso steady until October’s midterm elections. That is a staggering amount given Argentina’s limited resources, and it raises real doubts about how long this defense can continue. This leaves the country at a turning point. Without fresh inflows of dollars, stronger exports, or firmer political backing, the framework looks unstable.

If reserves run dry or investor faith collapses, Argentina may be forced into a devaluation that would mean higher prices, more volatility, and another blow to Milei’s program. Hopefully, this bailout can help change things for Argentina. Milei’s credibility depends on proving he can bring inflation under control and keep the currency within its limits. If that slips, Argentina risks falling right back into the same destructive cycle of crashes and crises that has shaped its past.

Contact Ethan at ethan.digiacomo@student.shu.edu