The Fed Rate Cut Frenzy: How September’s Policy Shift is Reshaping Investment Strategies

Ethan DiGiacomo

Stillman News Writer

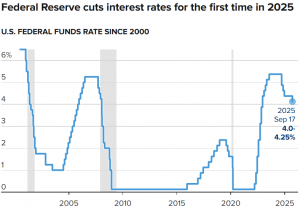

On September 16 and 17, the Federal Open Markets Committee (FOMC) met for its annual September meeting and for the first time in 2025 decided to cut rates by 25 basis points (BPS). Following the central bank’s decision to cut rates for the first time since December 2024, the federal funds rate will sit at a new range of 4% to 4.25%. The cut comes after the Fed left rates unchanged at its first five meetings this year amid economic uncertainty. The Fed plans to cut rates two more times by the end of the year, at their October and December meetings, with the plan being an additional 25 BPS cuts. This was all but certain, and the market reaction showed that it had been priced in. After the meeting, the S&P 500 and Nasdaq finished slightly lower, while the Dow rose. The Dow Industrial Average rose 0.57%, the S&P 500 fell 0.10%, and the Nasdaq fell 0.32%.

This marks the first Fed interest rate cut with Core Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) inflation at more than 2.9% in over 30 years. The Fed also updated its economic projections. The last time the Federal Reserve gave its projections was in June. They projected that the economy would grow at a rate of 1.4% this year. Now, they revised it upwards to 1.6%. In June, they projected that the unemployment rate would end 2025 at 4.5%. They left that projection unchanged at 4.5%. Currently, it’s at 4.3%, meaning it’s expected that the labor market is going to continue to weaken for the remainder of the year. While PCE inflation is moderating, their 2026 forecast was raised from 2.4% to 2.6%. It’s an indication that the economy is headed toward stagflation, a combination of high inflation and high unemployment.

Growth Over Inflation

The decision comes after the US Labor Department just revised -911,000 jobs out of 12 months of already reported data, the largest revision in history. U.S. businesses added just 22,000 jobs from July to August, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, and massive revisions to federal jobs data show that the pace of hiring was notably low in summer 2025. But Chairman Jerome Powell has another problem. The Fed’s purpose is to reduce unemployment and avoid inflation/deflation. This is the Fed’s “dual mandate.” Since 2021, the Fed has been laser-focused on the inflation side of this mandate. Inflation has not gone away; it’s rising. Core CPI inflation is at 3.1% and has never neared the Fed’s 2.0% target. But now the Fed needs to focus on the weak labor market. Although the Fed is being pulled in two different directions because of its mandate, Powell made it clear at his press conference that the Fed is now focused more on growth than inflation.

Drama in The Fed

This is a unique time for the Fed Governors. Unlike in previous years, the Fed’s Governors have dissented. The most famous being Stephen Miran. Miran is one of Trump’s economic advisors and a newly appointed Fed governor. He was the only governor who supported a 50 BPS cut, creating an 11-1 vote. Miran was selected by Trump in August to fill the seat that was vacated by former Fed Governor Adriana Kugler after she announced her resignation. He has said that he will take an unpaid leave of absence as chair of the White House’s Council of Economic Advisors rather than fully resign from the position. Miran was sworn into a vacancy on the Fed’s board on the morning of September 16th after Senate Republicans confirmed him the night before. His place on the Board will last until January 31, 2026, when Kugler’s term was set to end. Miran had the oath administered by a federal judge from Atlanta, rather than Powell or another Fed governor, as is customary.

Miran’s appointment and vote are not the only events related to Fed governors. Six out of 19 see no more interest rate cuts in 2025, while 9 out of 19 Fed officials see 2 more interest rate cuts in 2025. This is a massive divergence with just two Fed meetings left this year. Since becoming chair in 2018, Powell has faced three dissents at a policy meeting just once. In 2019, Fed officials were split over how and whether to cushion the economy against the possible side effects of Trump’s trade war with China. At their meeting that September, two Fed presidents voted against cutting rates at all, while another dissented in favor of a larger half-point reduction. Before July, the last time more than one governor dissented at a single meeting was more than 30 years ago. There haven’t been three dissents from governors since 1988. There is a question of Federal Reserve independence from the influence of the government. Miran’s appointment means the President has nominated three of the seven members of the Fed Board. Trump also said in August that he had fired Federal Reserve Board Governor Lisa Cook. However, a federal appeals court ruled earlier that he cannot fire her. The White House has said in response that it is going to appeal against that ruling to the Supreme Court.

Rates Decrease Yields Increase

Mortgage rates are climbing even though the Federal Reserve just cut interest rates. At first glance, that feels strange. If the Fed is lowering borrowing costs, shouldn’t mortgages also get cheaper? The Fed only controls short-term rates, while mortgage rates depend heavily on long-term bond yields, especially the 10-year Treasury. Right after the Fed’s latest cut, the 10-year yield moved higher to about 4.11%, which pushed 30-year mortgage rates up to 6.26%. Despite the rate cut, inflation concerns remain, and investors want more return if they are going to lock up money in long-term bonds. That demand for a higher return makes Treasury yields rise, and since mortgage rates are tied to those yields, they go up as well. The same pattern occurred last year. Before the September 2024 cut, mortgage rates fell in anticipation, hitting multi-year lows. But once the cut was official and the market realized inflation pressures were still strong, yields and mortgage rates reversed higher. Within months, mortgage rates had shot past 7%.

This shows how markets are always forward-looking. They do not just react to what the Fed does today. They react to what they think will happen with inflation, government spending, and the broader economy. For borrowers, this means lower Fed rates do not guarantee cheaper mortgages. Higher mortgage rates make homes less affordable, limit refinancing opportunities, and weigh on overall housing activity. Builders and buyers become more cautious, and price growth slows. What really drives mortgage rates is the mix of Fed policy, inflation expectations, fiscal concerns like government borrowing, and even global financial shifts. That is why mortgage rates can rise after a Fed cut. Investors see risks ahead and demand a bigger safety cushion. Until inflation pressures ease and long-term confidence improves, homebuyers and refinancers will face higher costs, even when the Fed is cutting rates. This is the second year in a row there has been this disconnect, and it highlights how complicated the relationship between central bank policy and real-world borrowing costs has become.

The Long Road Ahead

While the cuts to short-term interest rates may stimulate the economy by lowering borrowing costs, which should encourage investment, hiring, and consumer spending, hopefully adding more jobs to the labor market, the long-term is uncertain. The bond market is already showing a steeper 10-year yield curve because of the cut. Asset owners, like equities, real estate, or precious metals, will do extraordinarily well in the future. Assets are all climbing as the economy transitions into a fiscally dominant regime, a market-like approach to central banking, and concerns of the increasing fiscal deficit, and the Fed seems to have abandoned the inflation target.

There are several indicators that inflation is likely to be sticky. The U.S. is running a 7% of GDP deficit, which account for almost 50% of total corporate profits and gross savings. What that means is every year, 7% of the $30 trillion of GDP must get issued in new debt and bought by someone. The deficit is exploding and crowding out productive and private investment. Half of every single dollar of corporate profits and personal savings would have to go to buying US government debt every single year, which is just not possible. Negative real rates are coming that will be stimulatory and that will weaken the dollar both in purchasing power terms for the average American and relative to other currencies. Higher inflation and asset prices are also coming due to the weaker underlying denominator of the dollar. The K-shaped economy of the wealthier high-income earners and industries will continue to thrive while the rest of the economy continues to get worse. Ultimately, we are living in a fascinating moment in economic history. Rate cuts under these conditions signal a complex balancing act. It highlights the challenge of managing growth without fueling instability, especially with inflation still in play. Decisions like this often ripple through markets and everyday life in unexpected ways.

Contact Ethan at ethan.digiacomo@student.shu.edu