From Global Reserve to Gold Surge: The Dollar’s 2025 Crisis

Ethan Digiacomo

Staff Writer

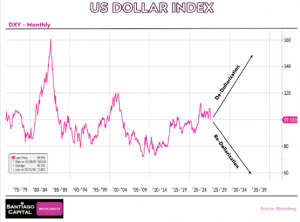

This month, the U.S. Dollar Index (DXY) has crashed to its lowest level since April 2022. Many are claiming this is the end of the dollar and the rise of gold as the new global reserve asset. The DXY is set at a base value of $100; any value above $100 signals a stronger dollar, while values below $100 indicate a weaker one. DXY is currently at $99, and it has been below $100 since April 11 for the first time since July 2023. The fall below $99 comes in the wake of a massive trade war that was sparked between Trump and the rest of the world on April 3rd, Liberation Day, when he announced tariffs on hundreds of countries, and this immediately caused the dumping of dollar assets as well as the dollar itself, causing the dollar to weaken about 8% in just about a month and a half. Now this weakening is seen as a massive boom for gold, which held true. Gold has raced upwards to above $3,300 per ounce, reaching almost $3,500, a record high, as of Tuesday, April 22.

Graph of the Gold Market as of 4/26/2025 (Courtesy of TradingView)

Why is the Dollar so Important

The U.S. dollar plays a pivotal role in global trade, serving as the primary currency for settling invoices, bills, and other transactions. Over 55% of worldwide trade is invoiced in dollars, while approximately 80% of interregional trade between developed nations is also conducted in USD. Beyond trade, the dollar is a key foreign exchange reserve for central banks. For instance, the Bank of Japan (BOJ) often purchases U.S. Treasury bonds to support the yen during BOJ interventions. Additionally, governments and supranational organizations, such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), use the dollar to underwrite loans. When the IMF extends financial aid to developing nations like Argentina or Venezuela, these loans are typically denominated in dollars, creating a demand for those countries to acquire USD to repay them.

The dollar’s influence extends to the foreign currency (forex) market, where traders speculate or hedge against interest rate and currency risks across nations. Some countries even adopt outright dollarization, using the USD as their official currency—examples include El Salvador and Ecuador. Remittances also contribute significantly, with hundreds of billions of dollars flowing from the U.S. to the rest of the world annually. For example, Indonesian workers in the U.S. often send money back home in dollar terms. Moreover, the USD is recognized as a safe-haven asset, attracting investors during global crises as a reliable flight to safety.

What is The Eurodollar

The Eurodollar market is a massive offshore dollar market that has come to drive the global economy. All the major foreign banks need to transact in USD, and the issue is that there just wasn’t enough US bank lending to satisfy the massive amount of dollar demand, so the foreign banks started making these loans in Eurodollars, which are synthetic dollars. The US dollar is the global reserve currency, so many nations buy and sell goods in dollars. After a country sells goods to another country, they have dollars that it needs to do something with. They could exchange them back to their native currency or deposit them in a bank to earn interest from lending. If they deposited in a US bank and participated in a lending program, there are strict Fed regulations that must be honored. Alternatively, the country could deposit the money in a non-US bank and lend it to another country or financial institution for a quick profit. This is the “Eurodollar” market: US dollars deposited in non-US banks for lending. This system creates a massive demand for dollars outside the U.S. For example, if there’s a Japanese automaker that needs a dollar loan, there could be a Saudi bank that wants to lend them money. Since 80% of all trades are made in USD, it makes sense to make the loan in USD. The oil refiner will ask for a USD-based loan, and now they have a debt instrument that they must pay in dollars.

The Triffin Dilemma

This generates external demand for dollars, leading to a significant amount of dollar circulation outside the U.S. financial system. As a result, the U.S. or U.S. banks must meet this demand, a concept highlighted by economist Robert Triffin in his 1960 testimony to Congress. The U.S. has two choices: they can either choose to fund that dollar demand by exporting enough dollars to satisfy dollar obligations abroad, which means that they are going to print more dollars than would otherwise be justified by their then Bretton Woods gold reserve ratio of $35 an ounce, or they would not do that, and the global economy would come to a halt as there wasn’t enough liquidity to grease the wheels of global market transactions. This decision is known as the Triffin Dilemma. What Triffin had pointed out did come to pass, but not in the way he thought.

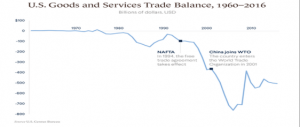

How the Trade Imbalance Started

In 1973 the U.S. went off the gold standard, getting rid of the gold redemption problem that was draining the U.S. banks and transferring the problem to fiat currency.

The U.S. then needed to determine how to export sufficient funds to keep the global economy running and ensure enough liquidity to meet all dollar-based obligations. Foreign producers, such as Japanese automakers, need a steady inflow of dollars to repay dollar-denominated loans, even though they earn revenue in yen, not dollars. So, they must find a way to either swap their currency for dollars in the forex markets, or they must ask the US for dollars directly. One way to ask is to export the U.S. manufacturing base. The U.S. manufactures everything abroad and has become a net importer of goods, making it a net exporter of dollars. This causes a trade imbalance that continues to get worse creates a problem of dollar recycling. Economies grow, and especially as they grow faster than the US, all these countries begin to earn in dollars, and they use these dollars to settle trade, to store foreign exchange reserves, etc. But while they’re holding them, they want to earn a yield from them. The best choice for risk-free yield is the U.S. Treasury market or U.S. equity markets. Thus, nations buy treasury bonds, which bid up treasury prices, which bring down yields, and makes it cheaper for the US government to borrow and get deeper into debt. The U.S. government gets to spend more money on war entitlements and infrastructure. As this money starts to flood into the U.S. system, the government agencies and consumers can buy raw materials and consumer goods imported from abroad and use that to fund a consumerist culture. And again, since these goods are coming from these developing countries, that money is now flowing outwards to these other countries, and it’s giving those countries trade surpluses with more dollars that they can use to recycle back into the U.S. financial system.

Why It Will Only Get Worse

As the dollar index weakens and dollar becomes cheaper relative to foreign currencies, the Eurodollar market debt and the foreign exchange reserves become more accessible for the global system to finance. Now, the dollar loan taken by an automaker in Japan is cheaper to pay off because the dollar is weaker compared to the Yen. Most of these Eurodollar debt holders can take out even more debt in dollar terms to finance their operations. When the dollar index goes lower, it creates a feedback loop where the dollar becomes weaker. It’s cheaper to borrow in dollars, and they take on more dollar debt. The next time that the dollar index rises, they now have more liquidity issues as they have more debt, and there’s more debt overall in the system. This has led to a massive amount of dollar reserves and foreign holdings of U.S. treasuries across the global monetary system.

Over time, the continual creation and distribution of dollars has undermined the purchasing power of the dollar, especially when measured against hard assets like gold. Gold, by contrast, does not rely on the credibility of a central bank or a government’s fiscal policy. It holds intrinsic value and is seen historically as a store of wealth. When the dollar weakens, it naturally takes more dollars to purchase the same quantity of gold. Additionally, when trust in the dollar or global financial stability wanes, investors often seek gold as a safe-haven asset. Thus, the structural forces that weaken the dollar, such as global dollar demand, the recycling of trade surpluses, and the massive expansion of debt, simultaneously drive gold prices higher. In conclusion, the very architecture of the modern dollar system, designed to sustain global trade and liquidity, paradoxically leads to the dollar’s gradual devaluation. As the dollar supply grows to meet global needs, its purchasing power falls, and gold, as a timeless store of value, rises in response. Understanding this connection helps explain why, despite short-term fluctuations, gold tends to thrive over the long term whenever confidence in the fiat dollar system begins to erode.

Contact Ethan at Ethan.Digiacomo@student.shu.edu