Cecilia Zvosec, Young Voice Blogger

MPH Candidate, Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health

MIA Candidate, Columbia University School of International and Public Affairs

Twenty years of scientific research has warned of the impact greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions could have on the earth’s warming, and a recent draft of the forthcoming International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report indicates that consensus on the negative effects of climate change has become even stronger. However, translating the complexity of climate change into effective policy and cooperation has produced mixed results – its framing as an environmental or political issue prompts resistance from climate change doubters and political actors alike. There are several ways that health workers and leaders can help build more effective climate change policy, including: using the health perspective to communicate the consequences of global warming, advocating for the integration of public health systems into adaption strategies, and recognizing the mutually beneficial outcomes of public health and GHG-reducing interventions. Global health organizations at all levels of governance can change the conversation about climate change while continuing to emphasize much-needed support for health programs.

The health impacts of climate change will be severe and are difficult to ignore: unprecedented spread of infectious and neglected tropical diseases, illness from pollution and heat exposure, and population displacement and agricultural disruption from flooding and severe weather patterns are just some of the health crises that will overwhelm health infrastucture. And vulnerable populations already suffering from lack of health resources will be disproportionately impacted.

Conveying the consequences of climate change in terms of its health impact has been shown to be an effective communication tool. A recent study profiled in TIME shows that presenting information on climate change in the context of its health consequences elicits the most supportive reactions to mitigation and adaption initiatives while also maintaining high levels of hope for the future. Physicians and health workers are well-positioned to effectively relay information on health risks while also prescribing behavior and policy change that can mitigate the health consequences of climate change.

Additionally, global health interventions are going to become increasingly important to climate change adaptation. Continuing to combat infectious and neglected tropical diseases, universalize immunization, strengthen health systems, and build robust disease surveillance would minimize the negative consequences of current and future health crises. Strengthening health programs and utilizing public health models of prevention, risk management, and preparedness would help build more comprehensive climate change adaption and mitigation policies.

Not only can health programs and messaging strengthen climate change adapation, but many health interventions and GHG mitigation strategies are, in fact, one and the same. Initiatives that reduce the use of cars and make urban areas navigable by foot, bike, or public transportation are also good public health interventions to increase physical activity. Improving agricultural practices to reduce GHG emissions can positively impact food distribution patterns and improve eating habits. Family planning initiatives that empower parents to space childbearing could also help manage unprecedented population growth, decreasing the impact of potential resource shortages. Sustainable energy solutions such as solar, wind, and carbon capture improve air quality, decreasing the risk of asthma while increasing overall life expectancy. The dual nature of such climate change and health interventions doubly emphasizes the utility of their success, and such programs can effectively communicate the impact of these interventions from both perspectives.

Just as global health and climate change strategies are interdependent, global health and climate change governance should work towards more effective collaboration. Global health governance bodies already participate in some climate change discussions: the WHO is an active participant in the The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), whose members negotiate guidelines for GHG reduction treaties, and the WHO has also developed strategies for advising other UN bodies on health-related climate change programs.

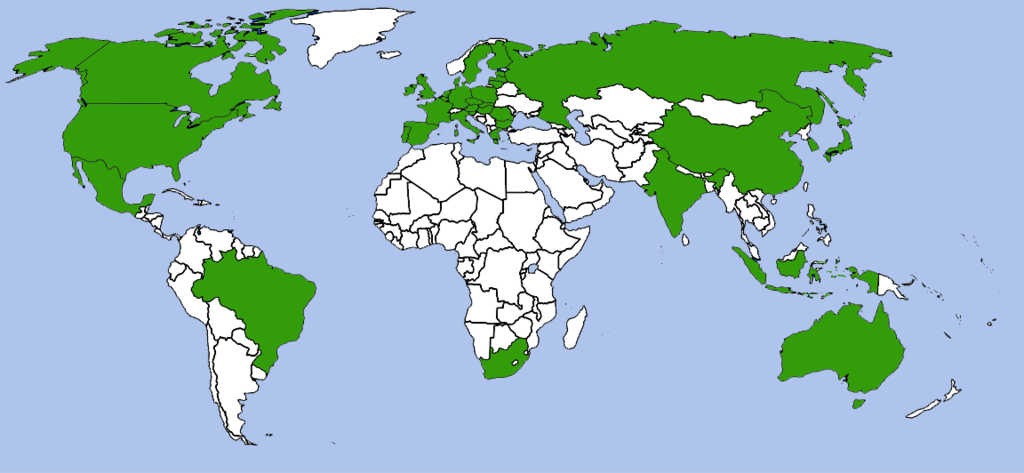

However, lack of confidence in multinational treaty negotiation has lead to a push for bilateral agreements and smaller-scale cooperation. The Major Economies Forum (MEF) is an example of a more flexible space where the United States and other developed countries can emphasize health in climate change discussions, and forums for developing countries will be just as, if not more, important. Bilateral emissions reduction agreements – like those the United States has recently negotiated with China and are working towards with India – should also emphasize the health sector’s role in adaption and mitigation. International organizations can also integrate health in their own climate strategies. In 2011-2012, the World Bank’s International Development Association dedicated about $2.3 billion to climate adaptation efforts, and another $2.3 billion to mitigating the effects of climate change. USAID has also developed their own strategy to support GHG-reducing sustainable development projects.

By more effectively communicating the impacts of climate change, contributing to the development of comprehensive adaptation and mitigation strategies, and emphasizing the public health benefits of GHG- reducing interventions, global health workers, leaders, and institutions can strengthen the argument for urgent and immediate action to combat climate change. By actively involving itself in climate change discussions at all levels – including multilateral bilateral, and institutional negotiations – global health governance can not only aim to develop more effective and compelling climate change strategies, but can also emphasize comprehensive support of global health programs and interventions in the process.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks