Learning from Histories of the AIDS Crisis

Joshua Busby, Contributing Blogger

Assistant Professor of Public Affairs, University of Texas at Austin

This is a cross-post with Joshua Busby’s blog on “The Duck of Minerva.”

What can we learn from histories of the AIDS crisis? Jacques Pépin’s The Origins of AIDS and Nathan Geffen’s Debunking Delusions: The Inside Story of the Treatment Action Campaign are two important contributions to our understanding of a disease that has now claimed nearly thirty million lives.

In different ways, both books raise interesting questions about what we can learn from history about causal mechanisms and wider sets of issues. In this two-part blog post, I’ll talk about each book and a recent set of review essays in Perspectives on Politics on Evan Lieberman’s important 2009 book Boundaries of Contagion: How Ethnic Politics Have Shaped Government Responses to AIDS.

Pépin, a Canadian medical doctor with a specialty in African sleeping sickness, has written a compact yet magisterial book that traces how the virus that causes AIDS leapt from chimpanzees to humans and then became a generalized epidemic in Africa that radiated around the world.

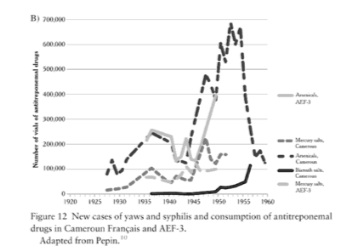

Pépin asks and answers a number of important questions in the book to weave a complex narrative of the worst health crisis since the Black Death. Could animals other than chimpanzees been the cause of transmission of HIV? (No. A hunter likely came in contact with chimp blood and picked up the disease and passed it on.) When and where, to the best of our knowledge did HIV originate? (Much earlier than we thought, perhaps as early as the 1920s and probably in central Africa in or near present day DRC). What role did colonial governments play in dislocating rural African societies and fostering the growth of male-dominated urban centers susceptible to prostitution? (By creating towns where only African men could legally live or by uprooting men to work on the railroads or the mines, the colonial powers disrupted rural populations and left large numbers of men without families and more likely to procure the services of the “oldest trade”). How did colonial era medical interventions to protect against other diseases like yaws and syphilis likely engender the spread of HIV? (Injectable drugs helped reduce the burden of infectious disease but poorly cleaned equipment likely helped spread HIV more widely). How did AIDS likely spread from Africa to and throughout the Americas? (One of 4,500 Haitian teachers in the Congo likely acquired the virus and brought it home where it became amplified through sexual tourism from the United States and the trade in blood which both spread the virus to hemophiliacs but also back to blood donors through efforts to separate out plasma).

As a political scientist, I found it fascinating how Pépin explicitly addressed alternative explanations for different facets of the argument. Even as Pépin sought to answer questions about AIDS, I learned a great deal about colonial era health practices, key protagonists in the fights against yaws and sleeping sickness, among other diseases. At each step, Pépin sought to engage rival explanations, “Could it have been this?”

At the same time, he consistently assembled a variety of evidence including colonial era statistics on trends in treatment of infectious diseases to sophisticated genetic evidence dating the origins of particular varieties of HIV with a margin of error.

In terms of policy and the present day, I was especially troubled how even well intended interventions to deal with other public health problems likely helped set the stage for the spread of HIV. This observation made me wonder how modern practices intended to enhance health and save lives (like the widespread use of antibiotics in animal feed) may create unanticipated consequences of grave proportions later on (such as drug resistance).

Even as AIDS continues to cast a large shadow over global health efforts, I wonder about our readiness for the next crisis and the leap of infection from animals to humans that proves both especially transmissible and deadly (or in light of the reports of manmade bird flu, from the lab to humans). Just this week, the Washington Post ran a story on the CDC’s efforts to test confiscated African bush meat for potentially lethal pathogens. The budget of this program: $59,740.

While I can’t say whether or not this amount of money is enough, I am worried that health agencies are being called upon to do more with less, in some cases much less. With the WHO having experienced unprecedented budget cuts in 2011 (nearly $1bn or almost 20% of its biennial budget) and the CDC having significant cuts of its own ($740mn or nearly 11% of its budget was cut between FY2010 and FY2011, are we becoming less capable in this time of economic crisis, even as our global health needs have grown?

In the next post, I’ll focus more on Geffen’s book and understanding the role of leadership in national efforts to address HIV/AIDS.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks