[A personal reflection by: Jose Nazario]

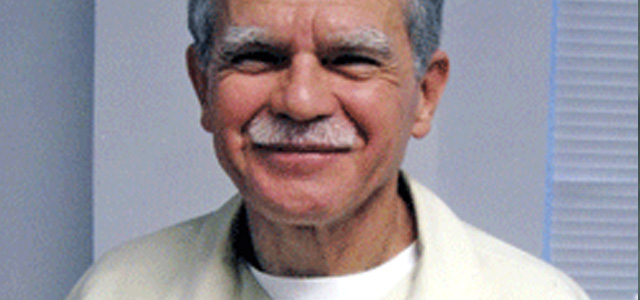

Oscar Lopez Rivera is a Puerto Rican independence activist, serving prison time since 1981. Rivera was born in San Sebastián, Puerto Rico on January 6, 1943, which is a holiday in Puerto Rico, but he wasn’t registered until January 8th, 1943. “I was five years old when I started school. By the time I started school my sister Clary had taught me how to write my name and the numbers from one to ten. She had also forced me to learn to write with my right hand although I was left handed. I was the youngest and the smartest kid when I started school but I had the habit of sneaking out of the classroom to go with my second cousin to the river. That’s how I learned to swim when I was five. I always stayed ahead of my classmates because my sister treated me as her student. In school I was full of mischief, fights, and pranks. During all the years I was in school in Puerto Rico I never stopped being me—an honor student with a bad boy attitude.”

Rivera’s family moved to the U.S. when he was an adolescent. Adapting to his new home, he managed English well enough to help the Spanish speaking adults in the neighborhood make their way through the maze of public and private services. Like many young Latino and African American men, he was drafted into the U.S. army. It was in Vietnam that Oscar began to understand what it meant to be Puerto Rican in the United States and the need for a people to control its own destiny. His service in Vietnam earned him the Bronze Star. When he returned from the war in 1967, he found that drugs, unemployment, housing, health care and education in the Puerto Rican community had reached dire levels and immediately set to work organizing to improve the quality of life for his people. Oscar worked in the creation of both the Puerto Rican High School and the Puerto Rican Cultural Center. He also participated in the development of the Committee to Free the Five Puerto Rican Nationalist Prisoners.

He was involved in the struggle for bilingual education in public schools and pushing universities to actively recruit Latino students, staff, and faculty. He helped to found educational programs at the maximum security prison for men in Stateville, IL. He worked in the community, fighting against drugs and police brutality. He also worked on ending discrimination in public utilities like Illinois Bell, People’s Gas and Commonwealth Edison. While those in the community respected his tireless work, the establishment took action to stop him in his tracks. He and other young Puerto Ricans, inspired by heroic guerilla movements throughout the world, decided their work for the independence of Puerto Rico could best be conducted in clandestine fashion.

He was arrested in 1981, accused of being a member of a clandestine force seeking independence for Puerto Rico, and sentenced to 55 years for seditious conspiracy. In 1988, as the result of a government-made conspiracy to escape, he was given an additional 15 years to his sentence. This will begin only after he has finished serving his original 55 year sentence. His release date is 2027, when he will be 84 years old.

From 1986 to 1998, he was held in the most super maximum security prisons in the federal prison system. The conditions there are not unlike those at Guantanamo under which “enemy combatants” are held; conditions which the International Red Cross, among other human rights organizations, have called tantamount to torture. Then, after seven years in the general population of a maximum security prison, he was transferred to a new, more harsh penitentiary which is the home of the federal death row. “Isolation from nature and human contact can break a man’s spirit. After along period in complete isolation I remember being transferred from that prison. There was a brief moment when I was able to step outside to the vehicle and remember catching a glimpse of something moving at the distance, a deer. That image stayed with me for the longest time.” In 2008, for the first time since his arrest in 1981, he was placed in a medium security prison, albeit with the unique condition that he report every two hours to corrections staff.

In spite of 32 years of adversity in prison, Oscar has maintained his integrity—political, physical, emotional, and intellectual. Physically fit, studious, and focused, he reads voraciously, keeps up to date with current affairs, and writes. He has also become a talented, prolific artist, whose drawings and paintings form part of an itinerant exhibit with Carlos Alberto’s ceramics, Not Enough Space. On the occasion of the 25th anniversary of his and Carlos Alberto’s imprisonment, the National Boricua Human Rights Network and the Comité Pro Derechos Humanos toured the exhibit throughout the United States, Puerto Rico, and Mexico.

Oscar’s daughter, Clarisa, lives in Puerto Rico with her daughter Karina. Because of the harsh conditions, including non-contact visits, Karina was not able to touch her grandfather until she was 9 years old. Their family visits are few and far between, because of the expense of long distance travel, and because arbitrary and punitive visiting policies serve as a disincentive.

For more information please see the following links and the links right to the page:

http://www.cdbaby.com/cd/laluchaesvidatoda

We often think of political prisoners as a thing of the past, with exemplars such as Nelson Mandela, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Aung San Suu Kyi. But Rivera is an example of a current political prisoner who has not only served for more than 30 years, but is still serving today.

Thousands have called for Rivera’s release, including Archbishop Desmond Tutu, former US President Jimmy Carter, Coretta Scott King, Nobel Peace Laureate Mairead Corrigan Maguire of Northern Ireland, and Puerto Rican Governor Gov. Alejandro García Padilla. In 2013, 24-hour demonstrations were conducted in both Puerto Rico and the US. Many other rallies and protests have held on his behalf. As a world, we need to remember that political prisoners are not simply a thing of the past. They can also be found in every country, including the US.