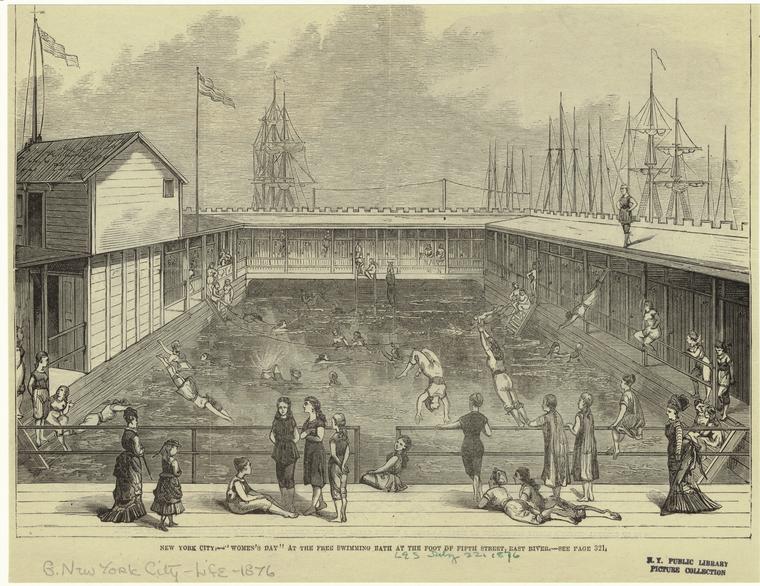

This image depicts what a typical “women’s day” looked like at the free-swimming bath located on 5th street in New York City during the 19th century. The image was issued in 1876 and the artist of the image is unknown. The image belongs to the Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints, and Photographs: Picture Collection of the New York Public Library.

During the 19th century, the United States was plagued by epidemic diseases. People valued exposing the body to nature’s elements because they believed this was a key to medical cures.[1] One of the elements people credited cures to was water. People also began to realize that exercise would aid in curing and preventing illness as well.[2] This lead to municipal swimming and bathing houses becoming popular establishments during this time. [3] The east coast began installing recreational river baths for the poor to assist in fighting disease and maintaining social order.[4] In 1870, New York installed two free municipal floating baths for the public. One bath was located on the West Side at the end of 14th street, and one was on the East Side at 5th street. Each bath was 85 feet long and 65 feet wide, with 68 changing rooms.[5] When the baths first opened, each gender had their own designated day. Women were given access on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, from 5 am to 9 pm, and these days were referred to as “women day.”[6] They were required to “furnish suitable bathing dress” in order to have access to the bath.[7] The turnout for the first women’s day was slim due to poor weather. However, on July 4th, 1870, the second women’s day had received a turn out of over 4,000 women.[8] The popularity of the baths grew, with 38,629 women attending in the month of August.[9]

In the image, we can see the structure of the bathing house. It was a one-story wooden box that “sheltered the tanks and the bathers from outside gazes.”[10] There appears to be stalls surrounding the complex which were provided for people to change in.[11] Outside of the bathing house you can see sails from ships, showing that the facility was floating on East River. This was done so that people could still swim in the river water but in a safer and more secluded environment.[12] The women are seen in bathing suits and clothing that are not very revealing. The women jumping into the bath appear to have jumpsuits on, which cover their bodies from right below the knee to right past their shoulders. The women outside of the bath how long gowns on, which cover them almost head to toe. This reveals how women from this time period were expected to show very little skin, even if they were gong to be surrounded by only women. This is confirmed by Bier as she stated, women were required to “furnish suitable bathing dress.”[13] The artist successfully portrays the ‘play’ aspect that was associated with bathing houses at this time. The women are seen jumping, diving, and flipping into the bath. Many of the women are interacting with each other or observing the fun going on. These buildings were originally designed to maintain hygiene and for orderly sport. However, the image represents that this objective became blurred as the baths became in use. Adiv states, “the boundary between hygiene, sport, and play, as see in [the image], was often fuzzy”.[14] Overall, the artist a great job of capturing what the bath looked like and how it was a fun, playful, and active experience all women and girls could enjoy.

[1] Nerea Feliz Arrizabalaga, “Adolph Sutro’s Interior Ocean: A Social Snapshot of 19th-Century Bathing in the United States.” Architectural Histories 9, 4.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Naomi Adiv, “Padia meets Ludus: New York City Municipal Pools and the Infrastructure of Play.” Social Science History 39, no 3 (Fall 2015), 431.

[4] Nerea Feliz Arrizabalaga. “Adolph Sutro’s Interior Ocean,” 4.

[5] Bier, Lisa, “Fighting the Current: The Rise of American Women’s Swimming, 1870-1826.” McFarland & Company Inc, 2011, 20.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid., 21.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Nerea Feliz Arrizabalaga. “Adolph Sutro’s Interior Ocean,” 4.

[11] Lisa Bier. “Fighting the Current,” 20.

[12] Nerea Feliz Arrizabalaga. “Adolph Sutro’s Interior Ocean,” 4.

[13] Lisa Bier. “Fighting the Current,” 21.

[14] Naomi Adiv, “Padia meets Ludus,” 432.