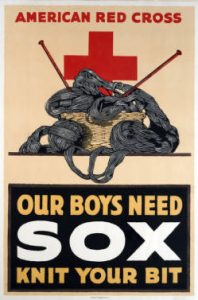

The Poster seen above was a part of the “Knit Your Bit” campaign, which was launched in 1917 by the American Red Cross shortly after the United States entered World War One. Through out the war there were dozens of campaigns that aimed to “mobilize the home front” and get Americans at home more invested in the war abroad. The use of posters, advertisements, and celebrity endorsements were hallmarks of a successful campaign at the time. For example, the “Liberty Bonds” campaign made use of these elements to incentivise people to buy bonds to help the government finance the war (Federal Reserve History, 2015). There were multiple campaigns to drive engagement running at the same time, so they had to angle themselves to appeal to specific niches and target audiences. The “Knit Your Bit” campaign targeted housewives by tying domestic labor to patriotism. Before long magazines like Ladies’ Home Journal began publishing about the initiative, bringing the war into the social sphere of people’s lives.

One of the major issues in World War One was soldiers developing health issues like trench foot. A condition that was a result of time spent in damp and muddy trenches, which if left untreated could progress into gangrene and often ended in amputation, effectively taking the soldier out of action. The best possible defense against gangrene and trench foot was wearing clean, dry socks. The need for socks highlighted a need for other garments like helmet liners, gloves, and scarves to help keep soldiers warm and free from illness on the front lines. It was from this need that the “Knit Your Bit” campaign was born.

Because the garments were being sent right from American homes to the front lines the American Red Cross began providing pamphlets and books with patterns and instructional materials to ensure that all of the items met the uniform standards. The availability of these materials made it even easier for the average person to participate and knitting circles began popping up all over the nation. Schools, churches, community centers, and homes became meeting places for women to sit, talk, and knit in support of the troops. During this period of time gender roles were strictly adhered to, and the ways in which women could contribute to the war were greatly restricted. The only real opportunities for women on the frontlines were nursing positions, but the draft had left many women as the sole providers and caretakers of their homes and families which complicated the matter of foreign service even further.

The “Knit Your Bit” campaign gave women an outlet to make a direct contribution to the war effort without leaving home. Every move of their knitting needles was a patriotic action, a stand taken in support of American troops. Rather than being forced to wait for news and worry, American women were finding opportunities to drive the nation forward. To keep the momentum going public figures began publicly supporting the campaign like First Lady Edith Bolling Wilson, who claimed to be an active participant in the movement and called on other women to knit their bit as well. Actress Mary Boland was also a supporter of the campaign with there being rumors that she may have hosted a knitting circle of her own on occasion. But the silver screen and White House were not the only influential sources of support.

The National American Woman Suffrage Association picked up the cause, actually writing about it in their official publication “The Woman Citizen” encouraging suffragists to participate praising it as a patriotic and noble cause. It was so encouraged that women around the country began writing into the “The Woman Citizen” to share how much they were knitting to support the effort; many even began forming their own suffragist knitting clubs. An example of this was “the Knitting 27th” from the twenty-seventh Assembly District of New York City, who knitted a set of garments for each of the seven hundred and twelve sailors stationed on the USS Missouri. It’s estimated that the suffragettes knitted around 73,491,216 stitches, spending nearly 41,000 hours knitting. And because they did all of this knitting using wool that had either been donated or purchased with donated funds, they saved the government between 6 and 7.5 million dollars in the process (Seyferth 2024). While not as iconic as other wartime initiatives, the “Knit your Bit” campaign was still a smashing success, which rallied the nation behind the military and put supporting the war effort at the forefront of citizens’ minds.