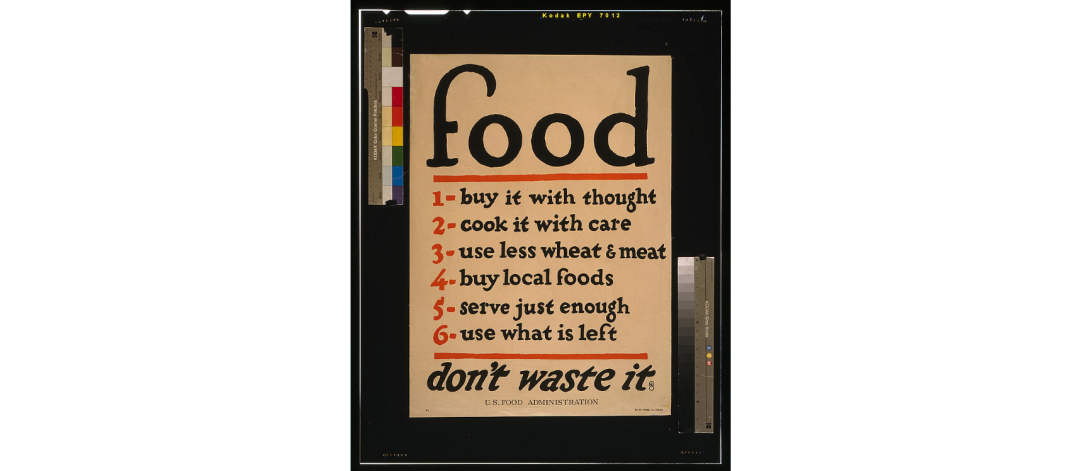

Just by taking a quick look at the 1917 U.S. Food Administration poster “Food, Don’t Waste It” appears to be almost too simple to hold any significance. The poster was created by Frederic G. Cooper. He made the poster very simple, with no imagery, decorative features, or patriotic symbols. Instead of making it bold, it lists six short rules about food. Even though it is simple, this is what gives the poster its power. Behind the few rules, lies a dramatic story about war, scarcity, national responsibility, and the ways everyday Americans were mobilized during World War I.

To understand the poster, it requires stepping into the world of 1917 in America. Just when an entire nation is preparing for its first major overseas conflict. When the United States first entered WWI, it faced the challenge of feeding both its own troops and millions of civilians suffering from shortages in Europe. To take care of this task, the federal government created the U.S Food Administration. Unlike European nations, the United States did not adopt mandatory rationing. Herbert Hoover started to promote a voluntary conservation campaign. This was to urge citizens to reduce waste and alter daily habits. Posters and slogans such as “Food Will Win the War,” started to appear every day, and there were programs set like “Meatless Mondays,” etc, to encourage people to change what/ how they were cooking and eating.

This poster that was created was on the tools used to communicate that message. With only words as the design, it resembles a household checklist. It encourages and invites people that see this poster to follow these rules. Having no images was intentional. Cooper relied on plain language and clear typography, making the message accessible in kitchens, schools, shops, and more. Each rule transforms domestic actions like buying groceries, serving meals, into a patriotic act.

This poster also reflects broader cultural trends. In Allison Carruth’s article, “War Rations and the Food Politics of Late Modernism,” wartime food campaigns are described as part of a larger modernization of American eating habits. Posters like this were able to encourage discipline, efficiency, and a sense of moral duty tied to food choices. In another article, Leslie Heller’s study of food and hunger in the early 20th century culture shows how food became an anxiety factor to others. Meanwhile, Robert Gross’s research on government messaging during WWI shows how propaganda was designed to reach everyone of all ages during this time. The poster’s simple and direct message made it easy for everyone to understand.

“Food, Don’t Waste It” offers more than a glimpse into wartime rationing. The poster shows how everyday life became part of the national war effort. It also shows how the government used propaganda to communicate and shape behavior. The poster gives brief commands, and it reminds us that history is often shaped not only by wars and leaders but by very big but yet quiet decisions made in kitchens across the country.

Footnotes:

(1)Carruth, Allison. “War Rations and the Food Politics of Late Modernism.” Modernism/modernity, vol. 16, no. 4, Nov. 2009, pp. 767–795. Johns Hopkins University Press.

(2)Gross, Robert N. “‘Lick a Stamp, Lick the Kaiser’: Sensing the Federal Government in Children’s Lives during World War I.” Journal of Social History, vol. 46, no. 4, 2013, pp. 855–879.

(3)Heller, Leslie. “‘I Cannot Live without a Macaroon!’: Food, Hunger, and the Dangers of Modern American Culture in Edna St. Vincent Millay’s Aria da Capo.” Modern Drama, vol. 54, no. 1, Spring 2011, pp. 1–23. University of Toronto Press.