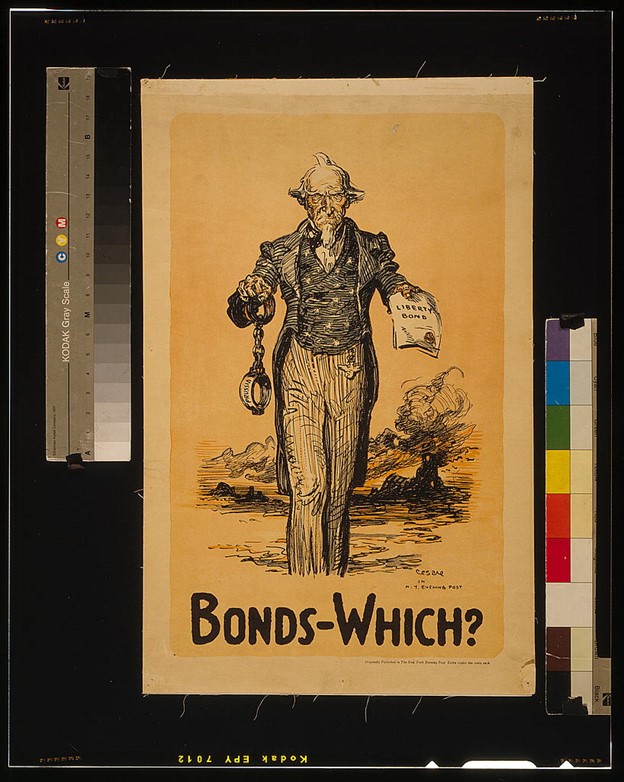

In the image, “Bonds -which?” from Cesare of the NY Evening Post (1917), the propaganda poster depicts an image of Uncle Sam holding chains in one hand and a liberty bond in the other hand with a train moving in a desolate background. In 1917 when this image was first published, the US was approaching the end of the Great War, having their military and industrial power tested on the world stage in a large-scale way as never seen before. At the time, the country was fighting for democracy to be maintained abroad, entering the war following the German’s refusal to allow the US free, safe trade of the seas without warfare. Additionally, Germany promoted a joint war effort against the US with Mexico, a proposal that was terminated with the interception of the Zimmerman telegraph. While America was fighting to sustain our independence and democracy overseas, our country took desperate measures to ensure the war was supported domestically and to negate backlash that could undermine the war efforts. For example, 16 months before the US entered the Great War President Wilson made a speech for the joint congress on December 7th, 1915 stating that immigrants “born under other flags […] have sought to bring the authority of the government into contempt,” and thus declared that the US must end the, “poison of disloyalty by “crushing” these “creatures” out.[1] In other words, although there was no credible reason to not trust immigrants or believe they were committing treason in order to aid their home countries instead of the US, Wilson sustained his campaign on “wartime, patriotic hysteria” [2]in order to gain unanimous support of his initiatives to suppress freedom of speech over baseless claims that some of our US residents were posing a threat to the success of the United States abroad. Consequently, this inspired Wilson’s passage of the Espionage Act of 1917, which said that anyone who displayed “insubordination” or “disloyalty” to the US in supporting their war efforts could face a fine of $10,000, imprisonment for 20 years, or both. [3] Thus, this shows the irony between the freedom America was fighting to maintain during the war, yet their willingness to punish those who opposed the war at home.

In contrast to the Espionage Act, there were effective marketing campaigns to increase national support for the war led by the federal government. One of the best government-supported initiatives to result from the Great War was the implementation of Liberty Bonds. The financial assets needed to supply the Great War were steep – spending had to increase twenty-five-fold from $750 million to $18.5 billion[4]. While many politicians wanted to raise taxes to fund the war, they believed that this would ultimately anger and distance Americans from supporting war efforts, especially the wealthy. Instead, the government created a program where Americans could “purchase government debt,” through Liberty Bonds, not only to fund the war but to show their patriotic loyalty if they were not serving in the war, by giving Americans a, “financial stake in the war effort, increasing the support of war.” [5] In addition to funding the war and boosting morale, the introduction of liberty bonds meant that Americans had to save their money for investment, which helped to decrease consumer consumption as well as to reduce prices from inflation as the result of war. [6]Additionally, it had the unintended consequence of, “increasing savings rates among households of modest incomes,” by promoting incentive to save money instead of spending excess wealth on consumerism, which was beneficial not only to middle class financial stability but is also one of the best ways to combat the wealth inequality, according to economists, since it helps close the wealth gap. [7]

Another reason why Liberty Bonds were so successful during this time is because of the way in which the bonds were marketed to the American public at the request of the secretary of the Treasury, William Gibbs McAdoo. McAdoo made the bonds available for a broad range from incomes, with the lowest investment set at $50, and provided installment plans for payments so Americans with modest incomes could afford the purchase[8]. Thus, while Americans with high incomes may have purchased more Liberty Bonds, the success of the campaign was due to Liberty Bonds being marketed as accessibly by ordinary American families across the country, creating universal support that united Americans of all socioeconomic classes during such turbulent times. Additionally, he didn’t make the selling of bonds continuous, instead relying on 4 liberty loan drives during the war with specific start and end dates with specific goals for funding. During these Liberty Bond drives; the federal reserve system was responsible for circulating stories about the financial success of people who invested in liberty bonds in local newspapers and publications that included “inspirational stories,” and “bond selling tips.” Additionally, the Liberty loan committee recruited religious and civic to sell Liberty Bond subscriptions via organizations including the Boy Scouts of America and the Young Women’s Christian Association (YMCA). [9]Additionally, Liberty Bonds “saturated” the media, as propaganda film shorts that circulated from Hollywood were displayed before movies, as well as Hollywood elites like movie stars and executives purchasing the bonds and informing the public of their purchases. [10]This was all done in an attempt to use influential film and media to promote everyday Americans to invest in Liberty Bonds through an outlet that was accessible to most Americans regardless of their social class since movies were a form of “relatively cheap entertainment.” [11] Liberty Bonds proved to be successful as the bond drives cumulatively raised $24 billion, which would be around $5 trillion with our standard of currency today.

As depicted in the image, Uncle Sam is at the forefront of the messaging since Uncle Sam has long been synonymous with symbols of American patriotism and duty. Additionally, the different objects that he is holding in his hands shows that he is giving the American people an option: will they support the Great War, or will they resist it? This is also symbolized by the title of the image, which is an open-ended question in itself. If Americans refuse to support the war efforts, they can pick physical bondage or chains. Additionally, the chains have the word, “Prussia” inscribed on them, a German state that was fighting alongside the Central Powers. Thus, the image seems to imply that if Americans don’t support the war, they are forfeiting a win for the nation and resigning themselves to bondage and oppression of their personal freedoms and liberties by the enemy, Germany. The blowing smoke in the background and a train pulling into the station may represent the threat of impending doom of the Central Powers arriving on US land if nothing is done to stop them. The other option that Uncle Sam gives in his other hand is a Liberty Bond. Liberty Bonds were government bonds that could be purchased by US citizens to display their patriotism as well as support the financial funding of the war.[12] Thus, the option that Uncle Sam offers through holding a liberty bond represents a stark contrast to the shackles in the other hand; it represents American patriotism and support for the war efforts. It also represents an option of American liberty, domestic bliss, and independence since Uncle Sam is offering them, thus implying that Americans have a choice in the outcome of the war, and if they choose correctly they can remain free and demonstrate their love of country. In addition to the images in the propaganda poster, the colors used demonstrate the context of the question being asked. The poster makes use of essentially black and white tones without introduction of any bright colors. This may represent how the question Uncle Sam is asking is vary narrow in scope and doesn’t give Americans a diverse array of options – either they support the war, or they are against the war with no in between.

[1] Walker, Samuel, “Presidents and Civil Liberties from Wilson to Obama: A Story of Poor Custodians,” Cambridge University Press (2012).

[2] Walker, Samuel, “Presidents and Civil Liberties from Wilson to Obama: A Story of Poor Custodians,” Cambridge University Press (2012).

[3] Forte, David F, “Righting a Wrong: Woodrow Wilson, Warren G. Harding, and the Espionage Act Prosecutions,” Case Western Reserve Law Review 68, Issue 4 (2018).

[4] Hilt, Eric and Rahn, Wendy M. “Turning Citizens into Investors: Promoting Savings with Liberty Bonds During World War I,” The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, Vol.2, No.6, pp.86-108 (2016).

[5] Hilt, Eric and Rahn, Wendy M. “Turning Citizens into Investors: Promoting Savings with Liberty Bonds During World War I,” The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, Vol.2, No.6, pp.86-108 (2016).

[6] Hilt, Eric and Rahn, Wendy M. “Turning Citizens into Investors: Promoting Savings with Liberty Bonds During World War I,” The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, Vol.2, No.6, pp.86-108 (2016).

[7] Hilt, Eric and Rahn, Wendy M. “Turning Citizens into Investors: Promoting Savings with Liberty Bonds During World War I,” The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, Vol.2, No.6, pp.86-108 (2016).

[8] Hilt, Eric and Rahn, Wendy M. “Turning Citizens into Investors: Promoting Savings with Liberty Bonds During World War I,” The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, Vol.2, No.6, pp.86-108 (2016).

[9] Hilt, Eric and Rahn, Wendy M. “Turning Citizens into Investors: Promoting Savings with Liberty Bonds During World War I,” The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, Vol.2, No.6, pp.86-108 (2016).

[10] Collins, Sue, “Star Testimonials and Trailers: Mobilizing during World War I,” Cinema Journal 57, No.1 (2017).

[11] Collins, Sue, “Star Testimonials and Trailers: Mobilizing during World War I,” Cinema Journal 57, No.1 (2017).

[12] Shi, David Emory, “America: A Narrative History,” W.W. Norton and Company Inc.2, Brief 11th Edition (2019).

Citations:

Collins, Sue. “Star Testimonials and Trailers: Mobilizing during World War I.” Cinema Journal, vol. 57, no. 1, Fall 2017, pp. 46–70. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1353/cj.2017.0055.

Forte, David F. “Righting a Wrong: Woodrow Wilson, Warren G. Harding, and the Espionage Act Prosecutions.” Case Western Reserve Law Review, vol. 68, no. 4, Summer 2018, pp. 1097–1151. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=sso&db=fth&AN=130519664&site=eds-live.

Hilt, Eric and Rahn, Wendy M. “Turning Citizens into Investors: Promoting Savings with Liberty Bonds During World War I.” RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, Vol.2, No.6, pp.86-108 (2016).

Shi, David Emory. “America: A Narrative History.” W.W. Norton and Company Inc., Brief 11th edition, 2019, p.908.

Walker, Samuel. Presidents and Civil Liberties From Wilson to Obama : A Story of Poor Custodians. Cambridge University Press, 2012. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=sso&db=nlebk&AN=443667&site=eds-live.

For more information, please view a video kept by the Library of Congress’s archives depicting the 4th loan drive occurring in NYC. The excitement in the video is felt as President Wilson is in a motorcade driving down the streets of NYC in a parade in September 1918, followed by Secretary McAdoo investing in the first Liberty Bond of the drive.