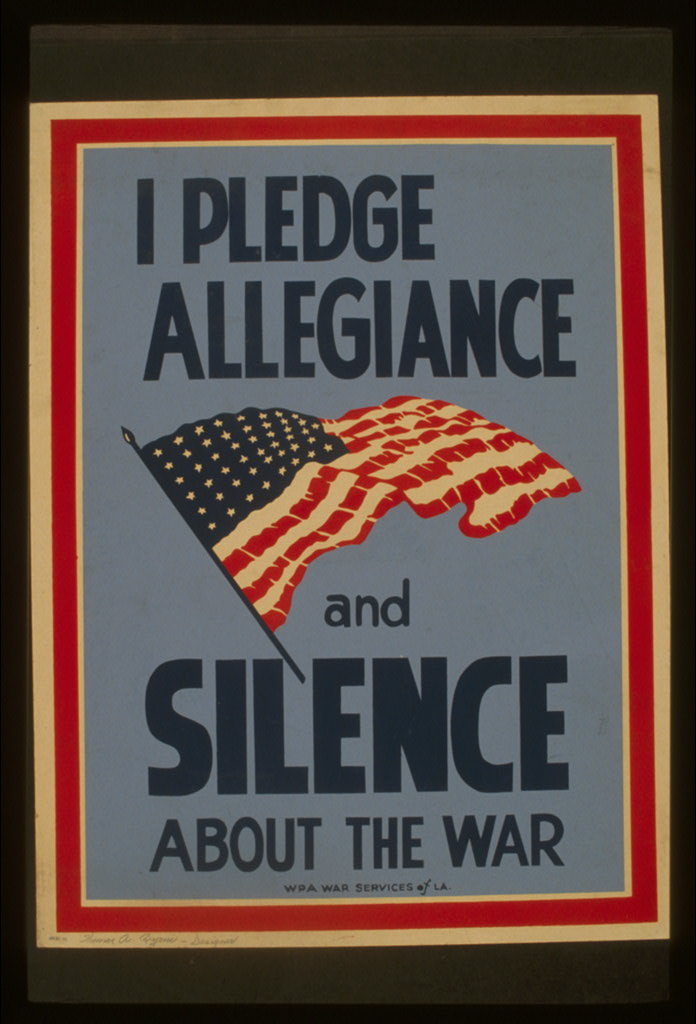

The wartime propaganda poster “I Pledge Allegiance and Silence About the War” was created by Thomas Byrne between 1941-1943 for the Works Progress Administration. The poster features a waving American flag surrounded by the words “I Pledge Allegiance and Silence About the War”, with silence being the bolded word. Patriotism and loyalty were valued during the war, especially on the home front. It was important that people showed their love and loyalty to the United States, while committing to reducing careless conversations regarding the war to prevent sharing sensitive information with the enemy that could be listening as spies.

Prior to the United States joining World War II, many Americans, especially President Franklin Roosevelt, were against engaging in international affairs or being involved in a war. As the tensions rose in Europe and Asia, Americans moved from an isolationistic approach to a neutral stance. President Roosevelt solidified this stance by creating the Neutrality Acts of 1935 that prohibited American weapon manufacturers from selling weapons to nations that were involved in the war, banned citizens from traveling by ships owned by war nations, and banned America from providing loans to nations in the war.[1] This changed two years later when the act was revised to include that nations at war could pay for nonmilitary goods through cash and have the products shipped on the nation’s own ships to ensure that America was still able to trade internationally. America’s end to neutrality happened when Japan launched a surprise attack on the U.S. military base in Hawaii, Pearl Harbor. The attack was in response to Roosevelt expanding trade on various resources, but purposefully leaving out oil, which was vital to Japan’s economy.[2] One day after the attack, Roosevelt and Congress agreed to declare war, initiating the start of the United States’ involvement in World War II.

Once America was officially in the war, there were significant changes made on the home front to mobilize and gain support for the war. Advertisement and propaganda became the biggest influences on the average American’s way of living. The use of advertising and propaganda was initiated during World War I but wasn’t popularized until the second one. During the First World War, the goal was to encourage the people of America to feel a sense of pride within their country, while also feeling an intense sense of responsibility to support war efforts. A multitude of posters during this time used shameful words to elicit public shame to feel as though they weren’t doing enough or used visuals of the enemy in a violent, bloody manner.[3] American poster artists used negative tones and imagery to shame citizens into participating in war efforts. Unlike the First World War, Roosevelt ensured that the images in the posters were positive images of Americans and created personal connections to the war efforts.[4] Through the positive imagery, the people of the United States not only felt a sense of pride, but it also encouraged those to participate on the home front or by serving in the military. In this war, men and women were both eligible to serve in the war, where previously, only men could and women were nurses if on front lines of war.

The “I Pledge Allegiance and Silence About the War” highlights the expectation to remain loyal and united, while suppressing the people from expressing doubts and limiting public discussion regarding the war. Roosevelt enacted the War Powers Act that allowed silence and censorship in America through new and adjusted agencies, while censoring all forms of communication amongst Americans.[5] The War Powers Act led to the creation of the Office of Censorship, monitoring media forms such as newspapers and radio broadcasters to ensure certain information that could be valuable to the enemy wasn’t expressed. It worked to authorize Congress to censor communication between the US and foreign nations through mail, telegraphs, or radio telephones.[6] The focus was to not only emphasize unity and patriotism but also shield the people from the horrors of the war to maintain morale and motivation on the home front. Journalists were significantly encouraged to provide their audience with the appearance of the war in an optimistic manner.

Media censorship was heavily implemented, it would cost a reporter their job if they discussed anything not approved by the government. This was the case of a journalist named Edward Kennedy, who evaded government censorship to report that Germany had surrendered. Kennedy was in Europe at the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force, which was led by Dwight Eisenhower, when he learned of the surrender. There was a plan devised to take representatives by plane to Berlin if Germany had ever surrendered. While in the plane, the U.S. government informed Kennedy and other journalists that they weren’t authorized to share the story to the public until the government approved. Once authorized two days later, there were still restrictions that prohibited the journalists from sharing the story, however, Kennedy published an announcement anyways.[7] Kennedy’s decision to bypass the censorship was controversial, but he received praise because he provided Americans with hope of the war ending soon. The purpose of the national censorship was to preserve the collective identity of being a united nation, as well as protecting national security. However, the limited speech and media showcase a constitutional contradiction. The First Amendment highlights that people of America are entitled to free speech, but it’s apparent that during the mobilization of the war, speech was limited and regulated by the government. America’s collective identity was portrayed in a manner that emphasized heroism and loyalism, but it stripped people from their individual identities and personal expressions regarding the war.

[1] David E. Shi, America: A Narrative History (Brief Twelfth Edition) (Vol. Volume 2), 12th ed. (W.W. Norton and Company, 2022), 1036.

[2] Ibid., 1047.

[3] Jessy Ohl, “Seeing World War I and Poster Propaganda with Fresh Eyes,” The Public Historian 42, Number 3 (2020): 127, https://www.jstor.org/stable/48744190.

[4] Terrence H. Witkowski, “The American Consumer Home Front During World War H.” Advances in Consumer Research 25, Number 1 (1998): 570, https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=458c779a-ada9-3c6a-9471-7a4a4ad78bf8.

[5] David E. Shi, America: A Narrative History (Brief Twelfth Edition) (Vol. Volume 2), 12th ed. (W.W. Norton and Company, 2022), 1050.

[6] Edward N. Doan, “Organization and Operation of the Office of Censorship,” Journalism Quarterly 21 (September 1944): 200, https://doi.org/10.1177/107769904402100302.

[7] Richard A. Fine, “Edward Kennedy’s Long Road to Reims: The Media and the Military in World War II,” American Journalism 33, Number 3 (2016): 320-322, https://doi.org/10.1080/08821127.2016.1204147.