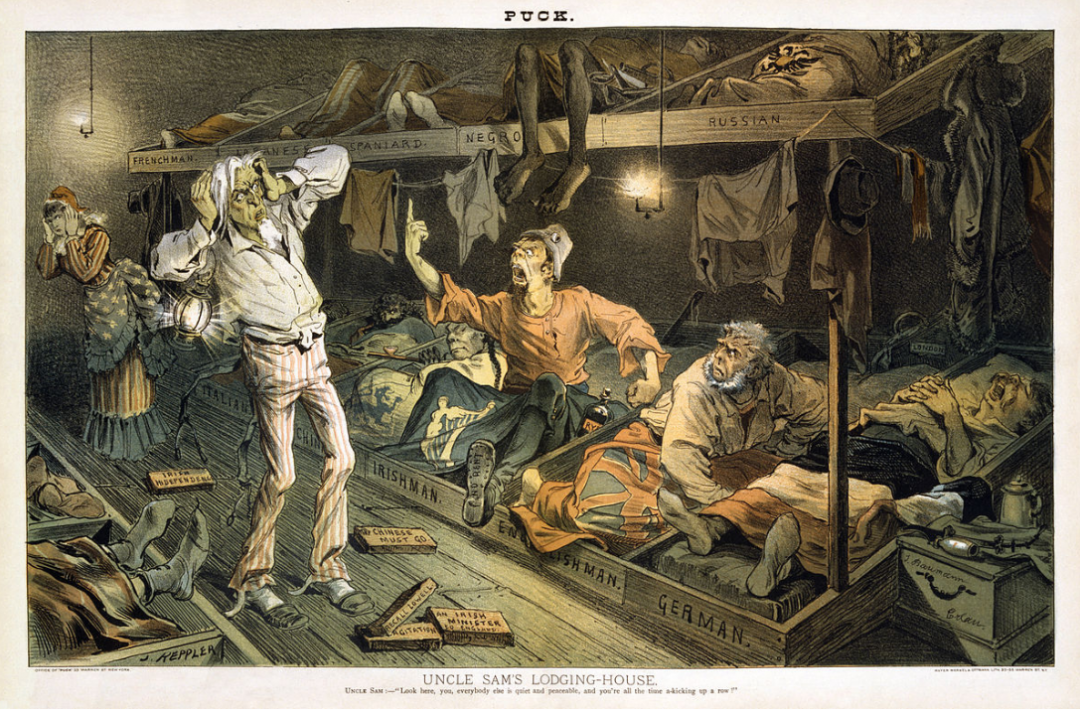

Joseph Keppler’s “Uncle Sam’s Lodging-House,” published as the centerfold of Puck on June 7, 1882, is a revealing commentary on late-nineteenth-century American anxieties surrounding immigration, urban housing, and political disorder. It was created by Keppler, an Austrian immigrant and cofounder of Puck, the leading satirical weekly of the era and with the cartoon it uses a caricature and metaphor to visualize fears about how different groups would coexist within the national “household.” This source is historically significant because it captures public attitudes at the moment the United States passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, and it reflects broader debates about how a modern, diverse, and urbanizing nation could maintain social order.

The cartoon depicts Uncle Sam standing inside a crowded, dimly lit lodging house where men of many nationalities occupy narrow wooden berths. An Irish lodger sits upright, shouting and waving a bottle of rye, disrupting men labeled French, Japanese, “Negro,” Russian, Italian, German, and Chinese. Bricks across the floor saying, “The Chinese must go”, “Recall Lowell”, and “Irish independence” which represents the political quarrels he has thrown into the shared space. The lodging room becomes a metaphorical microcosm of the nation, dramatizing the tensions among immigrant groups living together under Uncle Sam’s supervision.

When it comes to understanding why this cartoon resonated in 1882, it is essential to consider the social and political context. American cities in the late nineteenth century grew rapidly, and lodging houses became a major form of working-class housing. As historian Richard Harris explains, reformers viewed these houses with suspicion because of their “crowding, anonymity, and moral disorder,” conditions believed to “threaten the moral and social cohesion of the city” [2]. Boarding and rooming, Harris argues, nonetheless remained “an essential form of urban housing for those with limited incomes” [2]. These concerns shaped public opinion and helped explain why Keppler’s audience immediately recognized the lodging house as a symbol of both necessity and danger.

Contemporary journalism deepened these anxieties. An 1892 New-York Tribune investigation warned that immigrant lodging houses were “packed to suffocation” and often served as “breeding-places of vice,” where inspectors routinely found “filth, overcrowding, and clandestine political meetings” [3]. Although written a decade after Keppler’s cartoon, the article reflects attitudes already widespread in the early 1880s. Such accounts framed lodging houses as chaotic spaces where immigrant groups clashed, political agitation flourished, and traditional moral boundaries broke down showing exactly the fears Keppler visualizes.

Scholars like Mark Peel further show why reformers fixated on these spaces. Peel writes that lodging houses appeared to “promote a kind of antisocial behavior inimical to family and community ties, alienating native and newcomer alike from the bulwarks of moral order” [4]. Reformers believed such spaces contributed to the erosion of community life, replacing the social cohesion of neighborhoods and parishes with the “lonely self-absorption of lodgers.” Robert A. Woods, a leading settlement-house reformer, went so far as to describe the spread of lodging houses as part of “the advance of irresistible forces… pushing all the earlier types of American life entirely outside the confines of old Boston” [4]. These perspectives help explain why Keppler used a lodging house as the setting for national disorder as it represented, to many readers, the collapsing boundaries of a stable social world.

Keppler’s artistic choices reinforce this message. The lighting centers attention on the Irishman, who is brightly illuminated as he shouts and gestures wildly, while the others lie in softer shadow. This composition portrays him as the source of disruption, invoking stereotypes of Irish drunkenness and political agitation. Uncle Sam’s alarmed expression and Lady Liberty covering her ears suggest that the nation must intervene to maintain order. The labeled berths that are “Irishman,” “Englishman,” “Russian,” “Italian” invite viewers to see the room as a symbolic national household. The bricks on the floor, labeled with political slogans, function as visual metaphors for the ways contentious political claims could be hurled like physical weapons in a fragile, shared environment. The cartoon reflects Puck’s assimilationist editorial stance that diversity was acceptable so long as it remained orderly, quiet, and apolitical. By portraying the Irish lodger as the figure who disturbs the peace, Keppler implicitly constructs a hierarchy of desirable and undesirable immigrant behaviors. His message aligns with reformers’ concerns described by Peel and Harris, as well as journalists’ alarm about overcrowded immigrant spaces. The cartoon thus participates in broader debates over who gets to belong, who threatens the civic household, and how the United States should manage its increasingly pluralistic population.

In short, “Uncle Sam’s Lodging-House” is more than a humorous ethnic caricature. It is a compact visual editorial on immigration, urban life, and social order in 1882 America and by drawing on the material realities of lodging houses linked by reformers and journalists to moral disorder, overcrowding, and political agitation. Keppler crafted an image that chastises, instructs, and reflects the fears of a rapidly changing nation. Read alongside scholarship by Harris and Peel and contemporary reporting in the New-York Tribune, the cartoon serves as a valuable primary source that reveals the stereotypes, hierarchies, and anxieties that shaped American attitudes toward diversity during a formative era of national transformation.

Works Cited:

1.“File:Joseph F. Keppler – Uncle Sam’s Lodging-House.jpg – Wikimedia Commons.” 1882. Wikimedia.org. June 7, 1882. Link

2. Harris, Richard. 1992. “The End Justified the Means: Boarding and Rooming in a City of Homes, 18901951.” Journal of Social History 26 (2): 331–58. Link

3. “INVESTIGATING IMMIGRANT LODGING HOUSES.” n.d. ProQuest. Link

4. Peel, Mark. 1986. “On the Margins: Lodgers and Boarders in Boston, 1860-1900.” The Journal of American History 72 (4): 813–13. Link