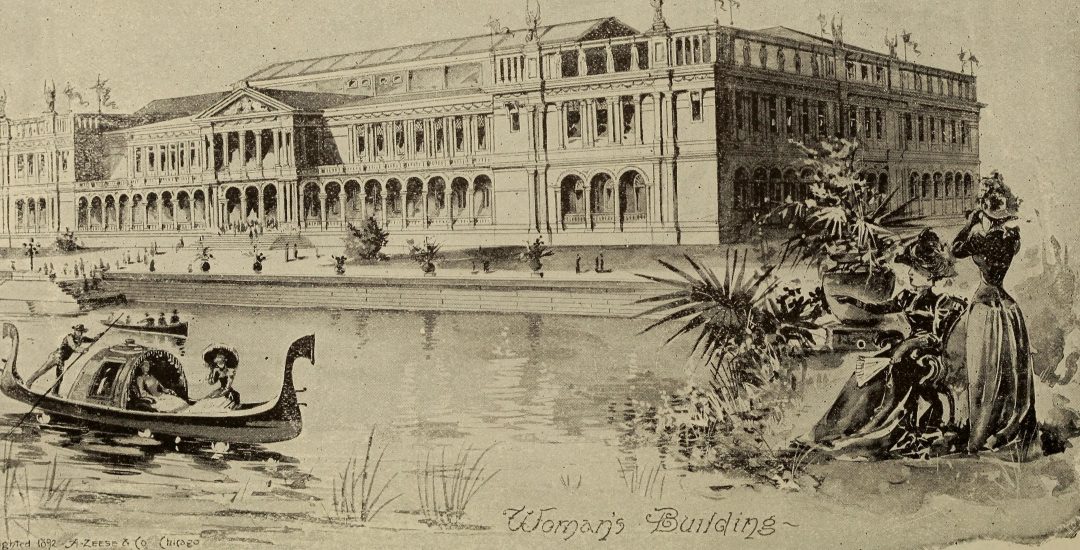

This piece [1], an illustration created for the book The World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893 and published by P.W. Ziegler and co. in 1893, shows a largely obscure yet extremely critical component of one of America’s most pivotal world’s fairs.

The illustration was only one of many illustrations, articles, and photographs in the book commemorating the titular World’s Columbian Exposition (commonly known as the Chicago World’s Fair), a grand event designed to rival Europe’s own international expositions and prove the country as just as valid as the others (including the one that they gained independence from!) across the sea. It was no small undertaking; it “lasted six months, attracted 27 million visitors… introduced attendees to the Ferris Wheel, shredded wheat, and belly dancing”[2], and transformed the image of Chicago from a filthy “Black City” that “led the nation in both criminal arrests and industrial pollution”[3], to a progressive, forward-thinking metropolis represented by the “White City.”

However, one of its most vital contributions came from one of its twelve buildings-the big and beautiful Woman’s Building, a place where the opposite sex was in full control. This is clearly conveyed in the illustration, where two women, both wearing fashionable gowns and flower-decorated hats, are in the foreground, front and center, with the building taking up almost half of the image. One woman points toward the building across the water. The other looks at it through a pair of binoculars, eager for a closer look at what it has to offer.

Indeed, the Woman’s Building had many things to offer for them, being planned, designed, and decorated entirely by women (not to mention that it was the first of the buildings to be completed). Its purpose was simply to commemorate and highlight their achievements. For the library, for example, works by women were not only chosen to be displayed, but “scrapbooks, club histories, cookbooks, literary miscellanies, literary history, women’s history, drama, poetry, and even novels” [4] were specifically produced for the occasion by thousands eager to gain worldwide appeal- a Columbian genre. Other exhibits covered inventions created by women, crafts made by women of diverse cultures around the world, and charts and graphs detailing women’s advancement in the industrial workforce, on the heels of the Second Industrial Revolution.

There were still several detractors, however. Some pointed out that a single building dedicated to the work of women would imply that they were only secondary to men. The world’s fair was a celebration of the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’ arrival in the Americas-reimagining him as an idyllic male hero whose “willful determination to traverse the Atlantic was linked to the strapping republic’s own westward-ho ambitions” [5]. As a result, his image was everywhere in the White City-up to and including. However, there was little to no mention of a Queen Isabella, or any other female figure. There was only Columbia, the generic woman whose only personality trait was being American.

Nevertheless, the Woman’s Building, while long destroyed (as with many buildings at world’s fairs) and not coming into the public consciousness again until recently, was a groundbreaking advancement for women in the United States in an era before suffrage, when many were still expected to be passive creatures staying at home and taking care of their husband and children.

Footnotes

[1] The World’s Columbian exposition, Chicago, 1893, P.W. Ziegler and co., 1893, pp. 436, 30 September 2025. File: The World’s Columbian exposition, Chicago, 1893 (1893) (14780354142).jpg – Wikimedia Commons.

[2] E. Searing, Susan. “Women in the White City: Lessons from the Woman’s Building Library at the Chicago World’s Fair,” American Libraries, Vol. 43, No. 3/4, 2012, pp. 44-47.

[3] Palm, Regina Megan. “Women Muralists, Modern Woman and Feminine Spaces: Constructing Gender at the 1893 Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition”, Journal of Design History, Vol. 23, No. 2, 2010, pp. 123-143.

[4] Wadsworth, Sarah and A. Wiegand, Wayne. Right Here I See My Own Books: The Woman’s Building Library at the World’s Columbian Exposition, University of Massachusetts Press, 2012, pp. 119.

[5] Sund, Judy. “Columbus and Columbia in Chicago, 1893: Man of Genius Meets Generic Woman”, The Art Bulletin, Vol. 75, No.3, 1993, pp. 443-466.