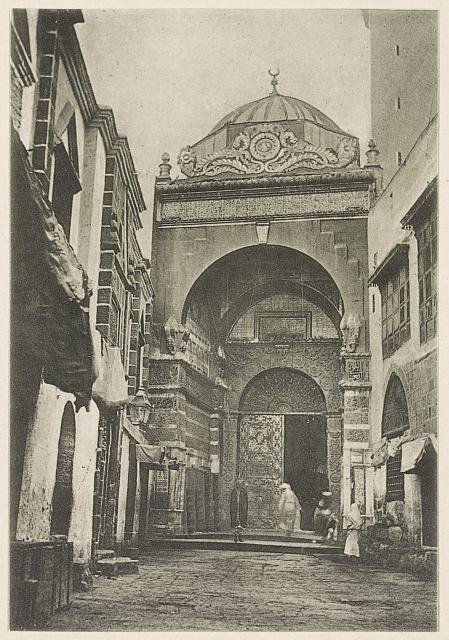

I went looking for an image to illustrate this blog and found in the Library of Congress’s online image archives this beautiful digital reproduction of a photo of the Main Gate of the Holy Mosque in Medina with its beckoning open door. Doors signify a transition from one space to another. Hanging in our hallway is a photo framed and signed by Tamara W. Hill of a similar door in Meknes, Morocco. I look at that door every day and it reminds me of my trip to Rabat. It is impossible in both cases to tell exactly what lies beyond, which makes these images so hauntingly mysterious.

The photo of the Main Gate of the Holy Mosque in Medina in the Library of Congress Archives contains the following descriptive metadata:

- Title: Medina : Haupttot (Bâb es salâm) der heiligen Moschee an der Südwestecke.

- Title Translation: Medina : Main gate (Bāb al-salām) of the holy mosque at the southwest corner.

- Creator(s): Moritz, B. (Bernhard), 1859-1939

- Date Created/Published: Berlin : Dietrich Riemer, 1916.

- Medium: 1 photograph ; photomechanical print.

- Summary: Photograph shows the main gate (Bâb es salâm) of the Holy Mosque in Medina, Saudi Arabia.

- Reproduction Number: LC-DIG-pmsca-38160 (digital file from original item) LC-USZ62-87128 (b&w film copy neg.)

- Rights Advisory: No known restrictions on publication. No known restrictions on publication.

- Call Number: LOT 3704, no. 69 [item] [P&P]

- Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 US

As the metadata tells us, the photograph was taken by Bernhard Moritz and published in Berlin in 1916. With this data, I was able to discover on Wikipedia that Moritz was a well-known German orientalist and linguist. The entry notes, “From 1896 to 1911 Moritz headed he library of the Khedive in Cairo. From there he often undertook expeditions to the Sinai and in the Hijaz (Arabia). In 1911 he returned to Berlin, where he became head of the Library of the Department of Oriental Languages and privy councilor. A few years later he was awarded the title of professor. In 1924 he retired.” The entry also contains Moritz’s normative data (Person) GND : 116,929,251 and Library of Congress number LCCN : nr95008447 This is what linked data is all about. I now have three reference points: a LC authority name and number and the German National Library number, with which I can use to further find information on Moritz. The Wikipedia entry was translated from German by a volunteer contributor (though I could have done it just as well with Google Translate). Since Moritz’s works are listed in the bibliography, I can now go to Amazon, Worldcat, or an out-of-print vendor to obtain his books. I have now benefited not only from linked data, but also from crowd-sourcing and a Google app–all in the space of under under three minutes and all done for free. This has to do with one aspect of information retrieval–the infrastructure that knits data together and there is a need for the library to participate in this process. Perhaps more important, however, is how adept a researcher needs to be to retrieve, interpret and then reuse this data to create something meaningful, rather than simply derivative. From everything that I’ve seen from working with students and from reading the library literature, this skill set takes a long time to master. It is not an easy cognitive process. Therefore, it is crucial for the university library to come up with a plan and policies as it transitions into both a technologically advanced repository and a teaching branch of the academy. It also is a good question to consider as I begin my trip to Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.