As a leader, it starts with being yourself and encouraging others to do the same

Leadership. It’s all different now. And it’s not going back to what it was. That is very good news. Which is not at all to say that the road to a new leadership paradigm will be easy. But leadership is becoming … human.

In 1980, 10 of the Fortune 500 Top 20 companies were oil companies. Four were automakers. The rest included companies in tech, telecoms, chemicals and steel, and a couple of conglomerates. These were not necessarily companies that valued people or diversity. Generally speaking, these were capital-intensive businesses, and the point was to produce reliable, accessible, efficient and undifferentiated output for other companies or for mass consumers who were obliged to take what was on offer. People were labor. Leaders were the people who told other people what to do and when.

Today, the Fortune 500 Top 20 is dominated by tech, retail and health-related companies. While some of them are better at it than others, it is fair to say that these industries value people in a different way than the capital-intensive, industrial companies of the past. For example, today’s Top 20 includes Apple, Alphabet and Microsoft. Like most tech companies, they rely on their employees’ intellect to create and design innovative products. Those products are targeted to digital natives who are hard-wired from an early age for personalization. For companies like these, brainpower, insight, human experience, intellectual capital, and new ideas are their lifeblood. The implications for leadership — how it is practiced now and how it will evolve — are enormous.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the shift in leadership ideas and values had already begun. Notably, giant asset managers began to demand that portfolio company CEOs define their company’s social “purpose.” In 2018, Larry Fink, founder and CEO of Blackrock, the world’s largest asset manager, declared that to prosper over time, every company must not only deliver financial performance but also show how it makes a positive contribution to society. He emphasized that companies must benefit all of their stakeholders, including shareholders, employees, customers and the communities in which they operate. Benefiting stakeholders such as employees, customers, and communities suggests shifting to a people-driven approach. This is a big ask, requiring a whole new mindset. And new skills and perspectives to go with it.

Just as corporate America had started on the path to orienting to this new north, COVID-19 struck. George Floyd, a Black man, was murdered by a white police officer in Minneapolis. Social justice and the fight against white supremacy resurfaced as a critical, existential issue for the nation and surprisingly, not surprisingly, the world. Climate change has become undeniable. Millennials, Gen Z, Gen X, and baby boomers co-exist under that same company umbrella, sometimes understanding each other and sometimes not. The national conversation around the place work holds in our lives and where that work actually takes place continues as CEOs at many organizations attempt to get workers physically back to the office. The much-anticipated Great Resignation is well underway.

In short, vulnerabilities of every kind in our society have been exposed. Getting to anything approaching normal requires a new kind of leadership, and that leadership paradigm continues to evolve. It will include a wider set of diverse voices and styles that break out of the narrow behavioral leadership models of the past to embrace people of all shapes, sizes, colors, creeds and genders who express themselves differently.

What does this mean for you and your leadership journey? Listen to yourself.

In my case, listening to myself is something I learned the hard way. In 2015, in the space of a few weeks, I lost my job, I lost my father, and then, after what was supposed to be routine throat surgery, I lost my speaking voice. As a corporate spokesperson and communications professional who had just lost both her income and her guiding light, the impact was devastating. I could not get my father back, but if I was lucky, I could restore my voice. I embarked on a medical journey to understand why I had lost my voice and how to get it back. At the same time, I realized that on a higher plane, after years of over adapting to succeed in business environments with little or no diversity, equity or inclusion (DEI), I had worked very hard to “fit in” and had erased myself in the process. I had surrendered my agency — my voice — and I needed to get it back.

Helping companies operationalize DEI for change is my way of valuing myself — leaning into my lived experience, historical knowledge, business acumen and cultural competency to help reset and restore our collective voice. And my own.

Be ready to forgive yourself.

In American society, we are rarely congratulated for our mistakes, possibly with good reason. Nevertheless, at some point (or points), you are going to make a mistake. The experience will likely be emotional and terrible. It might also be a gift that is — eventually — transformative. If you are truly leading, you are moving forward relying on incomplete information because while you can make a best guess, no one can predict the future. And even figuring out what you and your team should be doing, the present can be a challenge.

To quote former U.S. secretary of defense Donald Rumsfeld, “There are known knowns. There are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns. That is to say, we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns, the ones we don’t know we don’t know.” Between the known unknowns and the unknown unknowns — black swan and other events we just do not see coming — there is plenty of room for error. Even knowing the knowns of managing ourselves and others is fraught with the possibility of getting it wrong.

Be ready to forgive yourself. Because mistakes are going to happen. But if you don’t make mistakes, you aren’t doing it right. In a world where change is accelerating, you cannot avoid trying new things. Not making mistakes might mean you are sticking closely to what has worked in the past. Settling for the same results in a changing world means missing opportunities — and risks — associated with innovation and trying something different.

If you can forgive yourself for the mistake, you will then be able to look at what happened as clearly as possible to see if there is a transformative lesson to learn. If you are able to find that lesson, that gift — not an easy task by any means — you’ll be fine, perhaps even better than fine.

Get comfortable with diversity, equity and inclusion. All three of them.

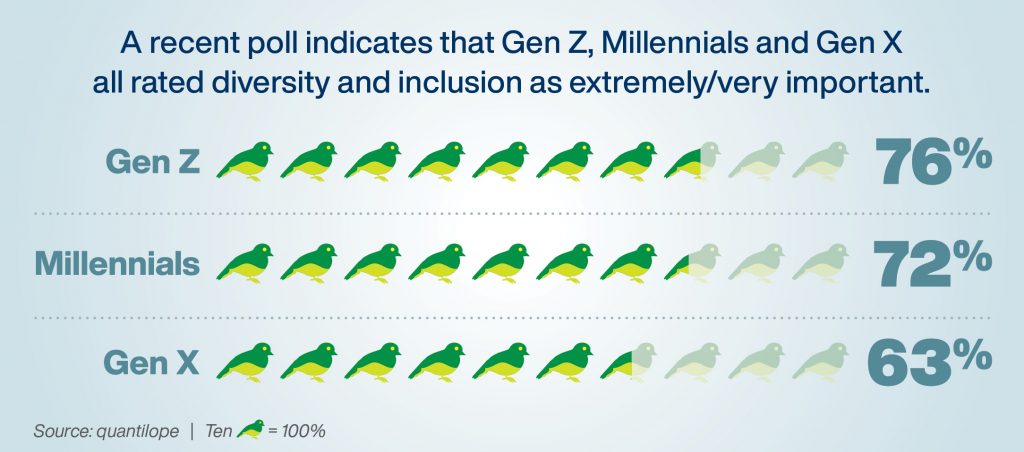

Whoever you are, whatever your race, ethnicity, gender, religion, age or ability, getting comfortable with DEI is a must. Those goals are not going away any time soon. A recent poll indicates that Gen Z (76 percent), Millennials (72 percent) and Gen X (63 percent) all rated diversity and inclusion as extremely/very important (source: quantilope). These generations already comprise the bulk of the workforce. In addition, older millennials are assuming leadership positions. With the Great Resignation unfolding as we speak, not getting DEI right is a risk for attracting and retaining employees at all levels. We also know it also means accepting suboptimal decision making and results. (McKinsey/Cloverpop).

Understanding the meaning of DEI and its implications for any leader or organization is not a no-brainer. These three concepts are different for every organization, and getting the mix right can be a tricky balance. As a leader, blind spots can make the right level of awareness and skills for yourself and for others hard to figure out and operationalize, regardless of your generation or diversity status. We all have blind spots, and it’s hard to know what they are because they are, well, blind spots! The first step is doing an informal self-assessment: How much do you know about other cultures? How comfortable are you with people “not like you”? How are you defining that? Then think about what the implications of what you are learning about yourself might be for your business, your employees, your peers, your community. Making an honest, preliminary notion of where you are, as best you can, is a start.

Be Yourself.

Everyone else is taken. While this adage is well-known, it is worth thinking about. According to Deloitte University, 76 percent of employees surveyed felt the need to hide their differences or “cover” at work. Covering is when individuals seek to downplay the importance of their visible identity, including adapting their appearances (clothing, hair) or changing their behaviors in ways that are uncomfortable for them. In this case, Blacks (94 percent), women of color (91 percent), LGB (91 percent), all women (80 percent), and straight white males (50 percent) all sought to diminish some aspect of their identity at work. Sixty-one percent of respondents stated that their leaders expect employees to cover.

This data suggests that employees are holding back on sharing their thoughts and perspectives, and are choosing to some degree to “go along to get along.” Going along with the dominant voice in the room results in suboptimal decisions and a stifling of the innovation that comes from the sharing and consideration of unique points of view. This data also suggests that leaders have not yet mastered and are not sufficiently modeling and driving inclusive behaviors.

While this requires training, learning and development initiatives across the enterprise to be sure, as a leader, it starts with being yourself and encouraging others to do the same. Depending on who you are and where you work, there can be enormous pressure to be someone else. Being yourself may sound like a platitude, but with only 24 percent of employees comfortable with being themselves at work, it bears repeating.

Linda E. Dunbar M.A.

Linda Dunbar is CEO & Founder of Diversity Decoder, a consulting, communications, coaching, and training company specializing in diversity, equity & inclusion (DEI). She graduated cum laude from Princeton University, and earned a Master of Arts in Law and Diplomacy from The Fletcher School, co-administered by Tufts and Harvard Universities. For more information, visit: www.DiversityDecoder.com