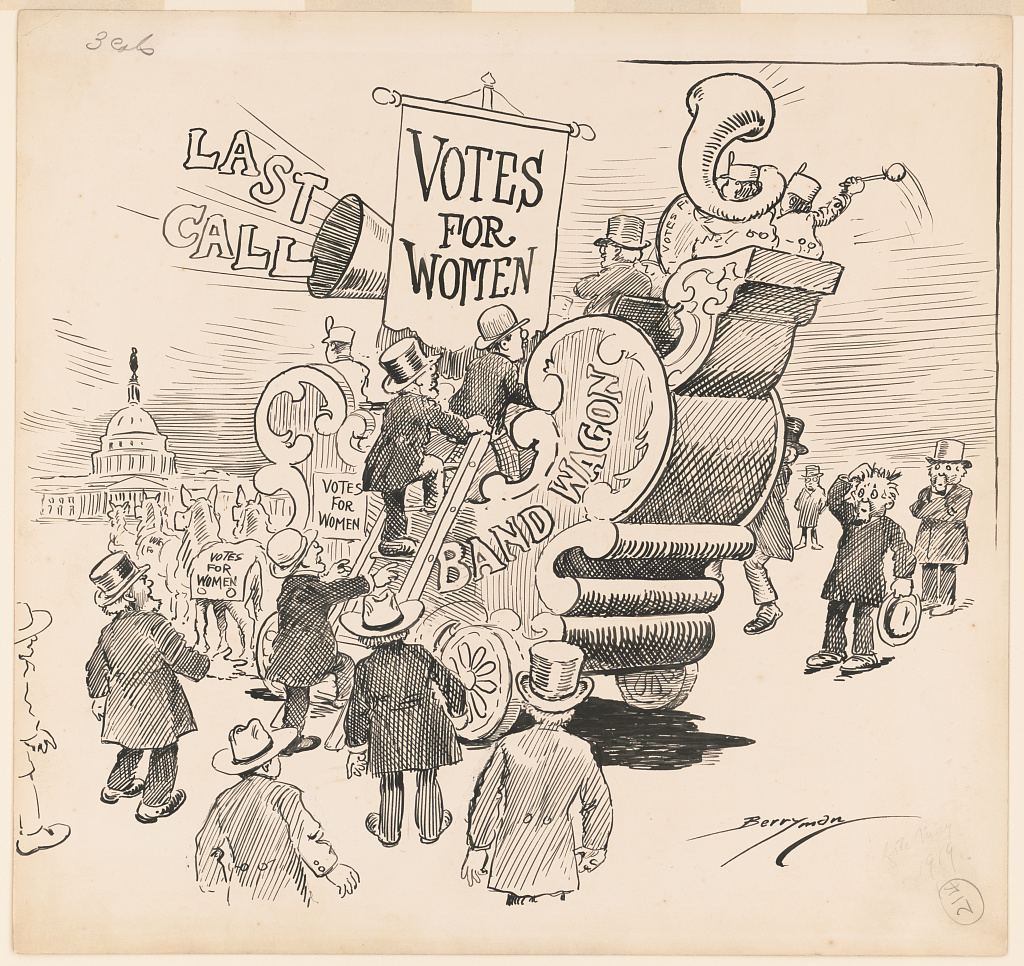

The Votes for women bandwagon political cartoon provided by the Library of Congress best describes the state of America, for women, around the twentieth century. The Women’s Suffrage Movement was established because “nineteenth and early twentieth century women who petitioned Congress lacked many of the rights American women have in the 21st century (today).”[1] The fight for voting rights from the federal level and eliminating voting restrictions were discussions among the suffragists; the most prominent suffragists were Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Stanton.

The suffrage movement was especially popular after World War I, which lasted from 1914-1918. Millions of young men joined the military force, opening many jobs and opportunities for women to enter the workforce. Women went into male-dominant careers such as factory workers, engineers, etc. However, when the war ended, and the men returned home, they returned to their jobs, and women were sent back home. Women wanting a new liberated life for them sparked a massive suffrage movement that ultimately changed the course of domestic life in America.

The political cartoon “Votes for women bandwagon” represented the suffrage movement’s successes and failures in Congress. The illustration was contributed by Clifford Kennedy Berryman and was published in January of 1918, predicting the congressional support of the amendment.[2] Pictured are many men climbing the ladder in support of suffrage, but not necessarily because they agree with it. As the “bandwagon” was already leaving, politicians saw no reason not to join the suffrage movement. Many congressmen felt a pull or influence from women in their lives, while others did not want to give up their freedoms as a man in society. The “bandwagon” was moving and growing in numbers, despite opposition. The vote ultimately came down to one pivotal man from Tennessee.[3] The Nineteenth Amendment would officially grant women the right to vote across the country. The “Votes for women bandwagon” illustration demonstrates two perspectives on women’s voting rights and signifies the “last chance” for Congress to demonstrate their support for women in America.

To begin, there was an abundant number of supporters of women’s rights across the fifty states already. Many states in America previously joined the “bandwagon” and supported women’s voting rights. In fact, according to the author and historian Lisa Tetrault, “When the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified in 1920, women were already voting, in some form, in all but eight states.”[4]

Many states supported women voting in elections several years prior to the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, with New Jersey being one of them. Although support on the state level appears to be promising, the true problems arises when the American Women Suffrage Association wanted the Constitution to be ratified to make women’s voting rights a federal amendment.[5] As demonstrated, women’s suffrage was endorsed throughout the majority of the fifty states. The support went beyond the women in protest and extended into the men in power in America, specifically Congress, as well. Ellen Carol DuBois, a historian, emphasizes in the journal “Interchange: Women’s Suffrage, the Nineteenth Amendment, and the Right to Vote,” that the Republican Party in Congress supported women’s rights for the long term. However, she also mentioned that a considerable amount of people within both the Democratic and Republican Party supported women’s suffrage by 1919.

In the ratification process, the state of Tennessee had a pivotal role. Tennessee was the last vote in Congress needed to grant suffrage in the nation for women. They became the 36th state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment and fulfilled the two-thirds majority rule requirement of the House of Representatives that was needed to pass the ratification. “The House voted on the resolution again on May 21, 1919, with 304 representatives voting for and 89 representatives voting against.”[6] About 200 of those “for” suffrage were Republican. In the Senate, the votes favored suffrage with “56 Yeas and 25 Nays;” the majority of those in favor were also Republicans.[7] Thus, although the support was overwhelmingly in favor of women’s rights, there were still about one hundred congressmen who opposed it or were hesitant and did not want to change the current societal structure in the twentieth century.

As exhibited, there were still quite a few politicians and people in the United States who did not want to join the “Votes for women bandwagon.” The majority of the Democrats in both the House and Senate were unsupportive of women’s suffrage. In addition, seven states in the conservative South did not approve the amendment.[8] A substantial factor in the opposition argument is the traditionalist male values that many did not want to change. If the traditional “societal roles” were to be changed, it would give women another chance to balance the power in the household.[9] Some men wanted to remain in dominance to women; women still suffered from pay disparities and expectations in domesticity, such as not getting a job and staying home and doing house chores.

Another essential aspect of the opposition of the Nineteenth Amendment is the apparent racism in everyday life towards African Americans that continued into the 1900s. Opposers of the Nineteenth Amendment were worried that the ratification would “threaten the political, economic, and social order of white supremacy that placed African Americans in a segregated, second-class status.”[10] Meaning, they were worried that women would vote for leaders or politicians who had a more modern, non-traditionalist, perspective. The major issue opposers had was that women would voice more concern over civil rights issues and other inequalities in America. Anti-suffragists also believed women voting would disrupt the racial and gender gap currently in society. Robert Jones in “Defenders of ‘Constitutional Rights’ and ‘Womanhood” stresses that this inequality was enjoyed by the top white male politicians, such as President Taft. In particular, North Carolina opposed women’s suffrage due to the “presence of a larger number of black residents” and the urge to keep voting restrictions to their advantage.[11] Therefore, many opposers watching other politicians join the “Votes for women bandwagon” were stunned, as they did not want to liberate more aspects of U.S. society.

All in all, the “Votes for women bandwagon” political cartoon, made in 1918, represents the division of supporters versus opposers of the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment. Although the amendment was approved through Congress, not all politicians supported the issue. Many men pictured in the cartoon are climbing or supporting the women’s voting rights cause, while others stand there in distress and confusion and watch the growing number of advocates. This proves that it took a massive fight to get to the position women are in today.

[1] Corinne, Porter, and Kathleen Munn. “Forging a Path to the 19th Amendment: Understanding Women’s Suffrage.” Social Education 83, no. 5 (October 1, 2019): 248–55. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=sso&db=eric&AN=EJ1234904&site=eds-live

[2] Clifford Kennedy, Berryman. Artist. Votes for Women Bandwagon. Washington D.C. Washington, 1918. [Jan] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2016679510/.

[3] Zornitsa, Keremidchieva. “The Congressional Debates on the 19th Amendment: Jurisdictional Rhetoric and the Assemblage of the US Body Politic.” Quarterly Journal of Speech 99, no. 1 (February 2013): 51–73. doi:10.1080/00335630.2012.749418.

[4] Lisa Tetrault, Ellen Carol DuBois, and Judy Tzu-Chun Wu. “Interchange: Women’s Suffrage, the Nineteenth Amendment, and the Right to Vote.” Journal of American History 106, no. 3 (December 2019): 662–94. doi:10.1093/jahist/jaz506.

[5] Lisa Tetrault, Ellen Carol DuBois, and Judy Tzu-Chun Wu. “Interchange: Women’s Suffrage, the Nineteenth Amendment, and the Right to Vote.” Journal of American History 106, no. 3 (December 2019): 662–94. doi:10.1093/jahist/jaz506.

[6] Zornitsa, Keremidchieva. “The Congressional Debates on the 19th Amendment: Jurisdictional Rhetoric and the Assemblage of the US Body Politic.” Quarterly Journal of Speech 99, no. 1 (February 2013): 51–73. doi:10.1080/00335630.2012.749418.

[7] Zornitsa, Keremidchieva. “The Congressional Debates on the 19th Amendment: Jurisdictional Rhetoric and the Assemblage of the US Body Politic.” Quarterly Journal of Speech 99, no. 1 (February 2013): 51–73. doi:10.1080/00335630.2012.749418.

[8] Robert B. Jones. “Defenders of ‘Constitutional Rights’ and ‘Womanhood’: The Antisuffrage Press and the Nineteenth Amendment in Tennessee.” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 71, no. 1 (April 1, 2012): 46–69. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=sso&db=edsjsr&AN=edsjsr.42628236&site=eds-live.

[9] Robert B. Jones. “Defenders of ‘Constitutional Rights’ and ‘Womanhood’: The Antisuffrage Press and the Nineteenth Amendment in Tennessee.” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 71, no. 1 (April 1, 2012): 46–69. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=sso&db=edsjsr&AN=edsjsr.42628236&site=eds-live

[10] Robert B. Jones. “Defenders of ‘Constitutional Rights’ and ‘Womanhood’: The Antisuffrage Press and the Nineteenth Amendment in Tennessee.” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 71, no. 1 (April 1, 2012): 46–69. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=sso&db=edsjsr&AN=edsjsr.42628236&site=eds-live

[11] Robert B. Jones. “Defenders of ‘Constitutional Rights’ and ‘Womanhood’: The Antisuffrage Press and the Nineteenth Amendment in Tennessee.” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 71, no. 1 (April 1, 2012): 46–69. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=sso&db=edsjsr&AN=edsjsr.42628236&site=eds-live