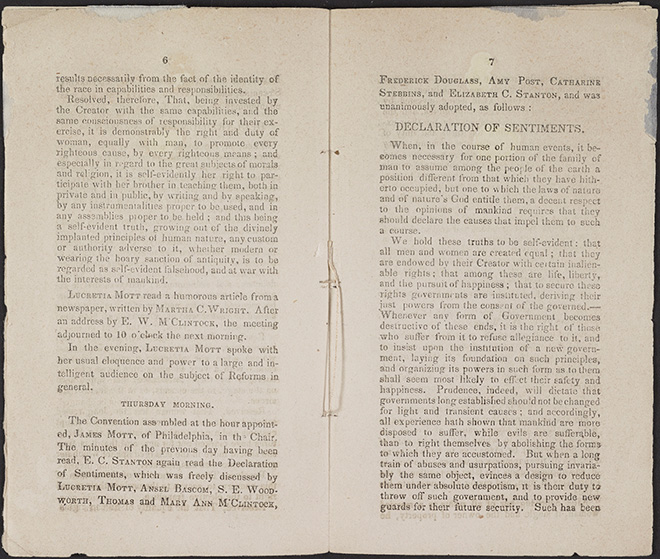

Drafted in New York in 1848, this “Declaration of Sentiments” provided by the Library of Congress highlights the growing interests during the nineteenth century in the women’s movement for suffrage as well as the reformation of society’s denial of women having rights in politics, economics, education, jobs, etc. The document, written by Elizabeth Cady Stanton, was proposed at the Seneca Falls Convention on July 19th, 1848, to fight against the inferior status of women. The Convention itself was held in Seneca Falls, New York, and followed the anti-slavery movement in which the women who organized the Convention were incredibly active. This reform movement sparked an awareness of women’s inferior position and inspired them to hold the Seneca Falls Convention in order to discuss eleven resolutions and their specific goals to “secure women the right to vote and hold property.”[1] The “Declaration of Sentiments”, which was the center focus of the Convention, had the specific purpose of asserting the equality of women by modeling the framework of the “Declaration of Independence” and creating parallels between the struggle for the rights of men with those of women. It is noticeable in the historical source that Stanton models that wording structure and parallels with the “Declaration of Independence” when she writes: “that all men and women are created equal” to include women in the major rights of “life liberty and the pursuit of happiness. ”[2] Not only Stanton advocated for the document, but “three hundred men and women attended the convention in the Wesleyan Methodist chapel; of those, one hundred signed the Declaration.”[3] Thus, the conversation about women’s suffrage began when the “Declaration of Sentiments” was proposed, and the Seneca Falls Convention gave women a place to find their voice and focus on the injustices at hand.

Prior to the start of the women’s suffrage movement, women were subjected to a specific gender role and were expected to be the primary caretaker of the household. This restraint required the women to stay out of the man’s sphere in areas outside the home such as working and voting. Since the colonial era, women “could not vote or serve on juries. College was rarely an option. A wife often had no control over her property or her children. She could not make a will, sign a contract, or bring suit in court without her husband’s permission.”[4] The “Declaration of Sentiments” not only spoke up against the gendered structure of society that existed in the United States during the nineteenth century but also the white male privilege that was causing the inequality.

This historical source exhibits that that time period’s gendered structure is what ignited the women’s drive for equality. After the American Revolution, there was a growing passion for removing the male separate spheres in society that was created by the male domination that existed. This was due to the Revolution’s emphasis on the patriotic nature of the war that in turn highlighted the inferior status of women because the war “stressed the political and military roles of men while ignoring the equally important supportive roles of women.”[5] Yet, this sparked outrage due to the unrecognized role women had in aiding the revolution as well, which is where the outrage began. For example, women had also “served the revolutionary army in substantial numbers as nurses and cooks, and in small numbers as combatants and spies; they had raised money for the war effort.”[6] It is noticeable in the “Declaration Sentiments” that Stanton sought to reiterate that women should be granted the same rights as men because they are just as significant to society’s development, yet they were never given the platform or representation to showcase their potential.

Although the Revolution highlighted the sex insubordination, the women’s rights movement was officially launched by the declaration at the Seneca Falls Convention because the convention was “significant for American women both symbolically as the birth of the modern feminist movement, and as a source of inspiration and direction in the long struggle for equality.”[7] For the first time in history, women were given a voice to promote unification and equality through the “Declaration of Sentiments”. The declaration accurately in pointing out the large cases where women under the law were not equal. Much of society belittled these identifications Stanton made due to the belief that they were “overstating their complaints” and did not need to be included in the political sphere.[8] Yet, everything highlighted in the declaration was truly needed and reflected nothing more than basic constitutional rights. For example, when Stanton demanded legislation, it would validate a married women’s rights “to the property they had brought into their marriages and to wages and income earned during the marriage.” [9] This was viewed as a large and unnecessary order because no woman had reached this extent of voicing against the confines placed upon women. It called upon women’s notable worthiness and created a platform for the rights that were owed to women.

[1] Harris, jennifer chapin. “Celebrating Women’s Herstory: The Story of Seneca Falls.” Off Our Backs 28, no. 7 (1998): 9–9. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20836139.

[2] Library of Congress, Seneca Falls and the Start of Annual Conventions, https://www.loc.gov/exhibitions/women-fight-for-the-vote/about-this-exhibition/seneca-falls-and-building-a-movement-1776-1890/seneca-falls-and-the-start-of-annual-conventions/declaration-of-sentiments/ accessed April 10, 2022

[3] Parker, Alison M. Review of The Seneca Falls Convention of 1848: A Pivotal Moment in Nineteenth Century America, by Sally G. McMillen. Reviews in American History 36, no. 3 (2008): 341–48. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40210932.

[4] Shi, D. E. (2018). America: A Narrative History (Brief Eleventh Edition) (Vol. Volume 1). W. W. Norton, 476. https://app.perusall.com/courses/2022_spring_hist1301wb-american-history-i/america-a-narrative-history-brief-eleventh-edition-vol-1

[5] Wilson, Joan Hoff, and Elizabeth F Defeis. “Role of American Women: An Historical Overview.” India International Centre Quarterly 5, no. 3 (1978): 163–73. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23001287.

[6] Kerber, Linda K. “FROM THE DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE TO THE DECLARATION OF SENTIMENTS: THE LEGAL STATUS OF WOMEN IN THE EARLY REPUBLIC 1776-1848.” Human Rights 6, no. 2 (1977): 115–24. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27879046.

[7] Wilson, Joan Hoff, and Elizabeth F Defeis. “Role of American Women: An Historical Overview.” India International Centre Quarterly 5, no. 3 (1978): 163–73. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23001287.

[8] Kerber, Linda K. “FROM THE DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE TO THE DECLARATION OF SENTIMENTS: THE LEGAL STATUS OF WOMEN IN THE EARLY REPUBLIC 1776-1848.” Human Rights 6, no. 2 (1977): 115–24. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27879046.

[9] Kerber, Linda K. “FROM THE DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE TO THE DECLARATION OF SENTIMENTS: THE LEGAL STATUS OF WOMEN IN THE EARLY REPUBLIC 1776-1848.” Human Rights 6, no. 2 (1977): 115–24. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27879046.