Washington D.C. is the home of American politics, but this diplomatic district was not founded at the same time as the nation.

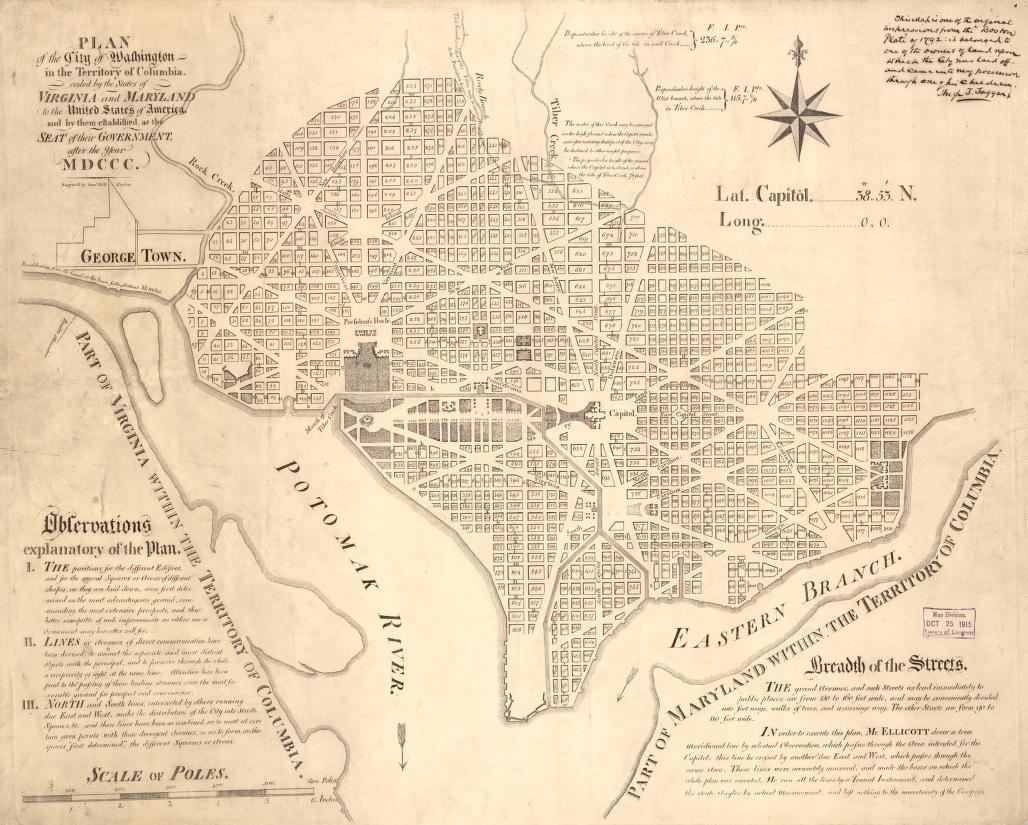

In 1792, after years of discussions and proposals, three men – Andrew Ellicott, Samuel Hill, and Hugh T Taggart – met in Boston to draft a blueprint for the United States’ capital and headquarters for the federal government. Their efforts led to this map, outlining the original plan for the layout of Washington, District of Columbia.

After the Founding Fathers signed the U.S. Constitution in 1787, they decided to put the federal government in New York City. However, by 1790, when sectional tensions were high, it became clear that the lawmakers and politicians needed a permanent, neutral place to call their own. And so, in June 1790, Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, and James Madison struck a deal, which would be known as the Compromise of 1790. Part of this agreement stated that the capital would be moved to Philadelphia for the next decade while a “ten-mile-square ‘federal district’ astride the Potomac River [and] sandwiched between the slave states of Maryland and Virginia” was being constructed. However, the ten-year time limit was slightly too ambitious as the workers had only just completed the Capitol and the Executive Mansion (later named the White House) in time for Jefferson’s inauguration in 1801.[1]

The process of developing and constructing Washington D.C. was detailed and laborious. Major Pierre Charles L’Enfant, a French engineer, was assigned to survey the land and develop a plan for the district’s layout. The map shows that most of the city has a north-south, east-west grid system. However, some streets cut diagonally. In a letter to George Washington, L’Enfant explains that these avenues go “to and from every principle place” and act as “veins” to keep the traffic moving into and within the region.[2] Two of these significant locations include the Capitol, purposely placed in the center of the district, and the Executive Mansion, slightly northwest of the city’s focal point. Between the two political buildings lies a large, open space that serves as a peaceful and convenient passage. The area of greenery also meets the mouth of Tiber Creek and the Potomac River, an additional point of entry and exit to allow government officials and federal business to continue flowing.

Challenges in the creation of Washington D.C. did not only come in the form of mapping out the city but also in getting the funding and resources to move forward with the project. The 1792 plan contains a total of 1138 lots, including the two major federal buildings. According to the scale provided on the map, the District of Columbia would be approximately 1200 poles (3.7 miles) from the furthest point east to the furthest point west and the same for north and south.[3] This amount of construction required an abundance of materials, which would prove difficult to come by. On September 21, 1791, L’Enfant demanded enough clay to create 3,000,000 bricks for solely the Capitol and the Executive Mansion.[4] But Washington and the other commissioners struggled to get the resources to the building site. The area near Washington D.C. was underdeveloped, with “few quarries and no mason yards, lumberyards, sawmills, limekilns, brickyards, or other services one would expect in cities like Philadelphia and New York.”[5] These extra transportation fees added to the already immense cost of establishing the capital of the country. While Jefferson planned to earn money by selling lots to the public, they still needed more for construction. Virginia and Maryland quickly came to the rescue by gifting the federal government $120,000 and $72,000, respectively.[6]

Building Washington D.C. was a large-scale, complex operation, but ultimately one that greatly benefitted the federal government and American politics. The original map of the District of Columbia may appear underwhelming and basic, but it offers valuable information and insight into the infancy of the United States. With a simple examination of the map, we can learn about colonial city planning and see how the federal district has changed and evolved.

[1] David E Shi. American: A Narrative History (Volume 1). W.W. Norton & Company, 2022.

[2] John Stewart. “Early Maps and Surveyors of the City of Washington, D.C.” Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C., Vol. 2 (1899): 48-71. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40066723.

[3]Andrew Ellicott, Samuel Hill, and Hugh T Taggart. Plan of the city of Washington in the territory of Columbia: ceded by the states of Virginia and Maryland to the United States of American, and by them established as a seat of government, after the year MDCCC. Map. 1792. https://loc.gov/item/88694162/.

[4] John Stewart. “Early Maps and Surveyors of the City of Washington, D.C.” Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C., Vol. 2 (1899): 48-71. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40066723.

[5]Robert J Kapsch. Building Washington: Engineering and Construction of the New Federal City, 1790-1840. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=sso&db=e089mna&AN=1619078&site=eds-live&custid=s8475574.

[6]Coolie Verner. “Surveying and Mapping the new Federal City: The first printed maps of Washington, D.C.” Imago Mvndi: The International Journal for the History of Cartography, Vol. 23 (1969): 59-72. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085696908592332.