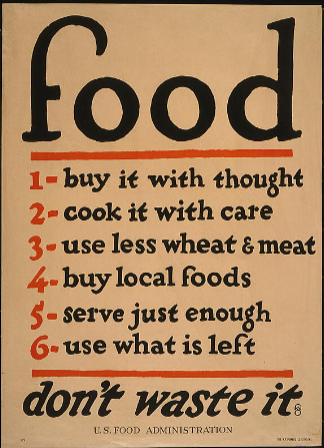

In 1917, artist Frederic G. Cooper created the poster above to promote the conservation of food for the American public. Until then, the United States had maintained a neutral position in World War I and provided the Allied forces with supplies to sustain themselves throughout the war.[1] According to Almon R. Wright in his article “Food Purchases of the Allies, 1917-1918,” the Allied forces in Western Europe “could count upon only 60 percent of their normal wheat production” and they consequently “turned attention to the sources of supply overseas” to aid in the hunger crisis they experienced.[2] However, Germany essentially forced the United States to become an active participant by sinking American ships carrying cargo for the Allied Powers.[3] On August 10, 1917, President Woodrow Wilson signed the Food and Fuel Control Act.[4] In the article “The Food Administration: Educator,” author Maxcy R. Dickson explains how the act “declared that national security and defense made it necessary for the Government to establish control over the supply, distribution, and movement of food, feeds, fuel…and equipment required.”[5] Around the same time the Food Control Act was enacted, Congress provided funds for the U.S. Food Administration to oversee the distribution of goods to Western European and American soldiers alike.[6] In the article “‘Food Will Win the War:’ Minnesota Conservation Efforts, 1917-18,” author Rae Katherine Eighmey quotes President Wilson as he urges “all Americans to become citizen soldiers” by conserving the food they consume to ensure that the Allied forces have adequate rations.[7] In turn, Wilson explains how a lack of “abundant food” would result in “the whole great enterprise upon which we have embarked will break down and fall;” essentially, food for the soldiers is the key to securing a win against the Central Powers.[8]

The creation of posters like Cooper’s resulted from the formation of the U.S. Food Administration and its 48 respectful divisions.[9] Of these, the Educational Division and its chief Ben S. Allen were responsible for making the country “stomach conscious” by informing Americans how they can consume food consciously and consequently aid in the war effort.[10] The main route the U.S. Food Administration took in completing this goal was the publication of “simple brochures and colorful posters with information and persuasive messages.”[11] Allen understood that the kitchen was “the first line of defense” in completing their goal and thus manufactured various posters in “women’s magazines and the women’s pages of the daily press.”[12]

In Frederic Cooper’s specific poster, the list of rules displayed has specific motives behind them that factor into the primary goal of providing troops overseas with proper supplies. For the first and fourth items on the list expressing the need to purchase food thoughtfully and locally, they were essential in ensuring that there was not an “unnecessary transportation of goods” since most means of transportation were utilized to ship supplies to soldiers.[13] By having citizens buy food locally, transportation could be reserved for war efforts and shipments could arrive at the frontlines in a timely manner. The second, fifth, and sixth items on the list coincide with one another because they focus on planning meals with conservation in mind to guarantee that homemakers “serve only what families would eat and save any leftovers for soups or hash on another day.”[14] By preventing food waste through careful prepping and storage, the conservation within “every household would make a difference” for the Allied forces.[15] Most importantly, the third item on the list advises the usage of fewer meat and wheat products because these items provided soldiers with adequate nutrition, which is further emphasized by their longer shelf life.[16] Since wheat and meat were vital for the troops, Americans were urged to pursue other means of incorporating grains and proteins into their diet through rice and beans.[17]

While the incorporation of such propaganda posters in magazines and newspapers seems like a small step to achieve the goal of conservation, its efforts proved victorious in the eventual success of World War I by the Allied Powers. For Great Britain in particular, they purchased 56 million pounds of frozen beef products in July 1918, which was twice as much as “all the airplane engines and parts purchased that month.”[18] Without the food supply, “all the chemicals, explosives, and metals in the world would have availed to nothing” if soldiers were not adequately fed and taken care of to fulfill their duties.[19] Overall, the conservation of food in American kitchens “fed the United States armies, bolstered the Allies, and made victory possible” amidst a food crisis that otherwise would have diminished morale and dragged Europe into anarchy.[20]

References:

[1] Eighmey, Rae Katherine, “‘Food Will Win the War:’ Minnesota Conservation Efforts, 1917-18.” In Minnesota History vol. 59, no. 7. Minnesota: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2005, 273.

[2] Wright, Almon R, “Food Purchases of the Allies, 1917-1918.” In Agricultural History vol. 16, no. 2. Washington DC: Agricultural History Society, 1942, 97.

[3] Eighmey, Rae Katherine, “‘Food Will Win the War:’ Minnesota Conservation Efforts, 1917-18.” In Minnesota History vol. 59, no. 7. Minnesota: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2005, 273.

[4] Dickson, Maxcy R, “The Food Administration: Educator.” In Agricultural History vol. 16, no. 2. Washington DC: Agricultural History Society, 1942, 91.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Eighmey, Rae Katherine, “‘Food Will Win the War:’ Minnesota Conservation Efforts, 1917-18.” In Minnesota History vol. 59, no. 7. Minnesota: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2005, 279.

[7] Ibid, 272.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Dickson, Maxcy R, “The Food Administration: Educator.” In Agricultural History vol. 16, no. 2. Washington DC: Agricultural History Society, 1942, 92.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Eighmey, Rae Katherine, “‘Food Will Win the War:’ Minnesota Conservation Efforts, 1917-18.” In Minnesota History vol. 59, no. 7. Minnesota: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2005, 274.

[12] Dickson, Maxcy R, “The Food Administration: Educator.” In Agricultural History vol. 16, no. 2. Washington DC: Agricultural History Society, 1942, 93.

[13] Eighmey, Rae Katherine, “‘Food Will Win the War:’ Minnesota Conservation Efforts, 1917-18.” In Minnesota History vol. 59, no. 7. Minnesota: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2005, 278.

[14] Ibid, 274.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Wright, Almon R, “Food Purchases of the Allies, 1917-1918.” In Agricultural History vol. 16, no. 2. Washington DC: Agricultural History Society, 1942, 98.

[17] Eighmey, Rae Katherine, “‘Food Will Win the War:’ Minnesota Conservation Efforts, 1917-18.” In Minnesota History vol. 59, no. 7. Minnesota: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2005, 276.

[18] Wright, Almon R, “Food Purchases of the Allies, 1917-1918.” In Agricultural History vol. 16, no. 2. Washington DC: Agricultural History Society, 1942, 101.

[19] Ibid, 102.

[20] Dickson, Maxcy R, “The Food Administration: Educator.” In Agricultural History vol. 16, no. 2. Washington DC: Agricultural History Society, 1942, 95.