Keaton Douglas had already changed careers once. She ran the marketing department of a Wall Street investment firm before changing focus to her original love: music and theater. “I had a journeyman’s career as a singer,” says Douglas. “I’m the great singer that no one heard of.” For 25 years, she sang at huge galas and worked with some of the finest musicians in the country.

But somewhere along the way, Douglas began suffering: her marriage fell apart while her son was very young. She was extremely hurt, but eventually she found healing — and regained her faith. The process of forgiveness brought her slowly back into the Church, she says. “And once I forgave, my heart changed. God had done for me something I couldn’t do myself: I was unburdened and unchained from resentment and self-doubt.”

She began to explore her Catholic faith and started to use her background as a performer to speak to groups of people about her devotion to the Blessed Virgin Mary.

That’s when she saw an advertisement in The Beacon newspaper for a one-day class at Seton Hall called “Spirituality and Public Speaking.” It sounded like it was created just for her, but her heart fell when she saw the schedule: the class was to be held on a Saturday, when she taught private voice lessons. Still, she decided to go and speak with the school anyway.

Dianne Traflet, associate dean of graduate studies at Seton Hall’s Immaculate Conception Seminary School of Theology, remembers the day Douglas walked into her office in 2012. “When she came in thinking she’d take a class, I saw not just a musician, but someone who is so enthusiastic about learning her faith,” Traflet recalls. As their conversation started, Traflet began to think: ‘Maybe this woman could use her vocal talents to inspire people through Christian music.’

But then she realized there was much more to Douglas. “She’s self-confident, enthusiastic, prayerful, so I just sat back and let her talk,” Traflet says. “I was seeing someone so ready to put her life in God’s hands, and so willing to wait on God for the next step she would be called to take.”

Douglas said she felt God was calling her to do something — though she didn’t know what yet. Traflet advised her to enroll as a student, take things one day at a time and see where the path led. “I said, it’s going to be fun to see what God has in mind for you,” she remembers.

That’s how Douglas enrolled as a master’s student in theology. As it happened, her son was headed to Seton Hall as a student that fall, and when his friends discovered her presence on campus, they told him how cool it was that his mom attended the same college.

Douglas found herself a bit out of sorts when she started taking classes at the seminary. After all, the last time she had written a paper, it was in the pre-computer era. On her second day, she was waiting outside a classroom when a young seminarian came up to her.

“You look like you could use a friend,” he said.

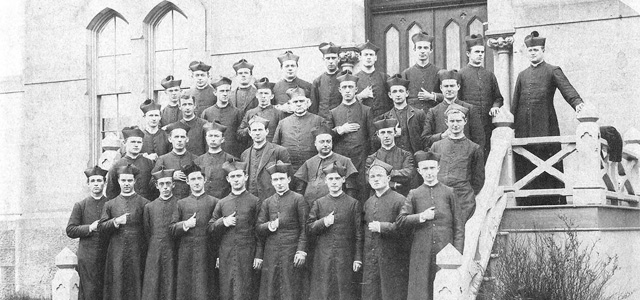

That seminarian was a student named Aro from a community of priests and brothers — Missionary Servants of the Most Holy Trinity — at the Shrine of Saint Joseph in Stirling, New Jersey. He’s now Father

Aro Varnabas, S.T., and he remembers the day well. “She looked very simple and very friendly — that’s why I approached her,” he says.

That seminarian was a student named Aro from a community of priests and brothers — Missionary Servants of the Most Holy Trinity — at the Shrine of Saint Joseph in Stirling, New Jersey. He’s now Father

Aro Varnabas, S.T., and he remembers the day well. “She looked very simple and very friendly — that’s why I approached her,” he says.

Soon, a fast friendship was formed, and he invited Douglas to a retreat at the shrine to speak to a group of women in recovery from heroin addiction. Douglas couldn’t understand why they wanted to hear from her, but she went anyway, asking herself, ‘What can I learn from these women?’

“I have sung in front of 17,000 people, but I was nervous in front of these women,” she remembers. “I told them how my life was put together by faith. I was crying, they cried. When I laughed, they laughed.” Douglas left the room with a changed view. “It did not matter what caused our brokenness. What’s important is that we are all wounded.”

At that moment, Douglas felt her life shift — she had felt called to serve others, and now she had an idea as to how. She began working as a regular spirituality speaker at Straight and Narrow, a recovery program in Paterson. “The recovery community became the audience that I prepared for all my life,” she says. “I could speak to them, and I just loved them.”

As her work in the recovery community deepened, she began to see the issues that all addiction — chemical substances, pornography, food — had in common. “The hallmarks were the same: the feelings of guilt, shame, unworthiness: these were at their roots part of one’s spiritual condition,” she says. “So we needed to provide a spiritual remedy. And who better to provide this than our Church?”

Douglas started training as a recovery coach. She dove into a course handbook and found that although it was 178 pages long, there were only two pages dedicated to spirituality. Many of her classmates in the course were in long term recovery themselves, and most had said they had had a spiritual awakening as part of their recovery.

That’s when she came up with the idea for “I THIRST,” a recovery program steeped in faith to give people spiritual tools to stay clean and sober. “I Thirst” is a reference to the words of Christ on the Cross, but it’s also an acronym: The Healing Initiative — Recovery, Spirituality and Twelve Steps.

The first part of the program is education and prevention: Douglas developed a curriculum to help the Church become a resource for people suffering from addiction. “It’s like no other disease because of the stigma,” she says. “Even bereavement is different.” People are often afraid to grieve a loved one’s death from addiction because of the shame — and that’s driving them from their faith communities. As part of the program, I THIRST volunteers hold assemblies for Catholic schools and youth groups that address addiction and focus on turning their attention toward faith.

The second part of I THIRST looks to train people to support the spiritual needs of those in treatment programs and prisons, and to sow the seeds of spirituality as a necessary element of wellness. “Some of the people in recovery are angry at God, some are resentful,” says Douglas, adding that teaching how to share love and hope to help people transform is crucial. It also includes retreats, which help people in recovery who are seeking spiritual guidance and community.

The program’s third prong is the development of aftercare and community-building services for people coming out of treatment facilities. Addiction isolates people, and so developing a community is a big part of the recovery process. Douglas hopes to welcome people back into the Church as a way to build this community and has developed a program of recovery Bible groups, recovery Masses and intercessory prayer sessions that trained volunteers can develop in their own parishes. Her office is located in a sober-living community in downtown Paterson.

The faith community’s proactive presence has been a missing element in recovery, Douglas says. One in six people in the U.S. struggles with addiction at some point in life, yet in 2017, only 4 million people received treatment, or about 19 percent of those who needed it. Drug abuse and addiction cost American society more than $740 billion annually in lost workplace productivity, healthcare expenses and crime-related costs.

That’s what makes I THIRST all the more necessary. Douglas has been working to pilot the program in the Archdiocese of Boston through Cardinal Sean Patrick O’Malley and its Opioid Task Force as well as other places in the Northeast, making presentations to different Catholic groups. She says many recovery programs are moving toward a clinical model and shying away from systems that integrate faith, like Alcoholics Anonymous or Narcotics Anonymous.

There’s a real opportunity for the Church to lead in this area, says Father Aro. “The problems of the society are also problems of the Church,” he says. “Every priest or religious person, anyone working in name of church, has to be involved in people’s real problems. That’s how we can reach out to them and bring them back to church.”

Traflet says it’s been a joy to watch Douglas’s evolution from that meeting in her office eight years ago. “She’s doing something specific that hasn’t been done before in developing this curriculum that is grounded on faith and Scripture, she says. “She’s very humbly entering into this, using the tools that she was given through her studies.”

Part of Douglas’s success with I THIRST comes from her authenticity, she says. “This is a woman who knows how to pray, and she wants to be able to bring people into a place of prayer as they’re recovering. She understands the power of prayer personally.”

Douglas is bringing the I THIRST program to Seton Hall’s South Orange campus for continuing education units. Undergraduate students also learn about the program through the core curriculum. Douglas explains that while studying transformation in the work of Socrates, Plato and Dante, for example, students learn about the transformative nature of recovery. Students speak with people in recovery and learn stories from real transformative ventures.

Douglas continues to feel called to bring faith to addiction recovery. For too long, she says, too many have acted like the priest and the Levite in the Good Samaritan story — walking past someone bloodied in the road.

“Maybe it was because we didn’t understand the nature of the disease of addiction, but we are commanded by Christ to care for one another, no matter what,” she says. “Addiction is messy; it’s hard to understand a lot of trauma and abuse; it’s tender and difficult.”

Engaging in recovery communities has changed Douglas, too, bringing her closer to understanding her own vulnerabilities. She still sings every day to inspire people, using her gifts to lift up people who are feeling ill in detox centers or who are alone in their recovery. She often chooses a well-known song such as “Lean on Me“ or “Amazing Grace.”

Douglas hopes to bring people back to their faith, and she hopes the Church will open its arms and welcome back those who have lost their way. “There is no group, no element of society that is exempt,” she says. “It’s a unique opportunity for a Catholic university to understand this disease and use our spirituality to reach out to people of all faiths, to share the spiritual healing that they do not get in regular treatment.”