People in the ‘60s wanted to be different,” says historian Elizabeth Cobbs. “They didn’t want to just not be their parents. They wanted to find a way to be better Americans. And I think the Peace Corps was just absolutely about that.”

As Cobbs writes in her book, All You Need is Love: The Peace Corps and the Spirit of the 1960s, when the program was founded it “reassured a broad cross-section of Americans during a turbulent period that there was at least one aspect of their nation’s policy that was indisputably good.”

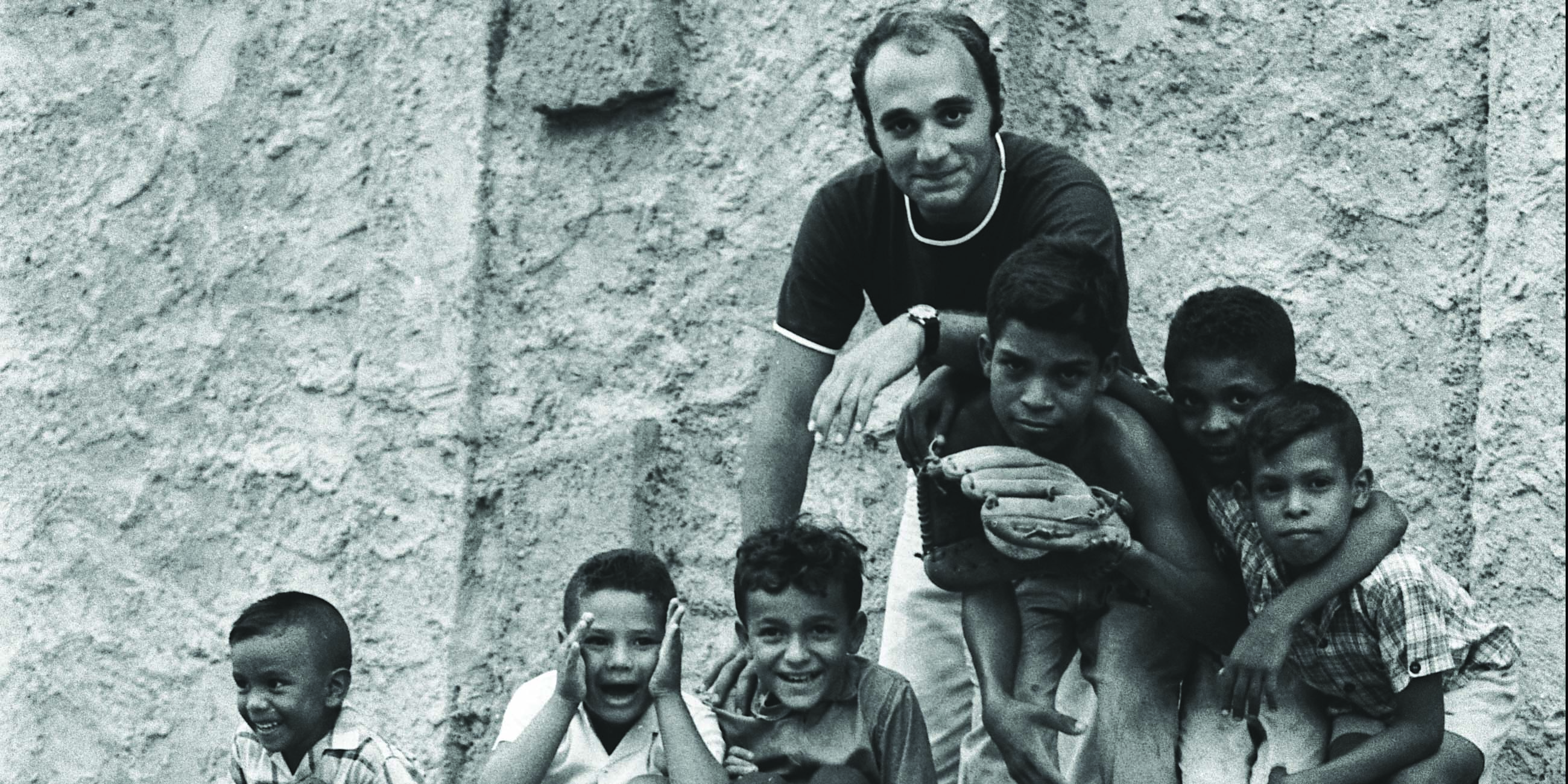

Tony Galioto ‘67, who did a two-year Peace Corps stint in Colombia in the ’60s, can relate. Sort of. He had earned his psychology degree from Seton Hall and didn’t know what he wanted to do. But the agency created in 1961 by President John F. Kennedy seemed a good fit. Galioto “was very much a Kennedy fan back then. It was the ‘60s; it was a time, I thought, of kind of a new world.”

New, indeed, for a guy from New Jersey to arrive in Colombia.

“Unbelievable. Get off an airplane, there’s cows in the street. It was total shock,” he said.

But before long, Galioto learned a bit of Spanish and was put to work as the photographer in a “slum rehabilitation office” in Cartagena to document the work that needed to be done. He also coached youth sports teams and helped run camps to keep kids busy in the summer.

“We lived in the barrios; we lived with the people. And it was pretty cool. People kept coming by and staring in the windows to see what these gringos were doing.”

Some of the work was fundamental, like trying to improve irrigation or sewage treatment. But there were opportunities for broader teaching, as well.

“I remember going into the governor’s office with some people from the barrio and having them ask for help, and they were so shy,” Galioto recalled. “It was like they were embarrassed to be in the governor’s presence. One of the things we tried to teach them — and it’s very difficult to change a culture — is that you have rights, you’re citizens.”

Some of the influence of the Peace Corps, though, is less tangible.

“One of the biggest impacts we had is that the people understood that these gringos weren’t these terrible people from the colossus in the north,” Galioto said.

“But just the fact that we were there, that we were living with them, that we were just trying to help. It was kind of an outreach program from one country to another. And once people got to know us, they saw we didn’t have any other motives but to help.

“I think the biggest shock was coming home,” said Galioto, who went on to become an insurance executive for more than 30 years. “The shocking thing to me was the luxuries that I grew up with. I still vividly remember taking my first shower [back] in my parents’ house. [In Colombia], I had been taking a shower off a lead tube that we constructed in the back yard. I really appreciate my country more, and people just don’t understand what it’s like [in other countries] and the extent of the poverty that people live in.

“No matter why the volunteer is there and what they’re doing, the fact that they’re there is probably the most important thing,” Galioto said. “They’re helping, they’re living among the less fortunate and caring for them. That’s huge.”

The Peace Corps concept succeeded at the time, historian Cobbs says, “because it was one of those events that was in the air.” Kennedy, she said, sensed that young people had a desire to go abroad and help the less fortunate. “A really good leader doesn’t just invent something out of whole cloth, but rather somehow channels the popular spirit and will and then takes it to a new level,” she said.

Fast-forward several decades, and Seton Hall graduates feel some of that same spirit.

Daria Preston ’12 worked with the Peace Corps starting in 2014 as a public-health coordinator in Guatemala. Her focus was on the country’s “Healthy Schools” program.

Preston said she learned about the Peace Corps at age 12 when she began doing volunteer work. Community development became her top interest as she continued volunteering in high school.

“Ultimately, though, I’ve always considered the Peace Corps as the greatest personal challenge I could undertake,” Preston said, “and for years, I had been dreamily saying ‘Someday, I’ll join the Peace Corps.’ In a way, Peace Corps has been shaping my life for years.”

The Alaska native, unlike some Peace Corps workers who struggle to adjust, described her arrival in Guatemala as nearly idyllic.

“I just remember being unbelievably happy. In many ways, arriving in Guatemala was an affirmation of my own ability to overcome obstacles and achieve goals,” Preston said.

“I was entirely consumed by how welcoming and humble my host family was. Their caring and help in acclimating us to a new country and culture was utterly invaluable. My Spanish at the time was still a bit rusty, and I fondly remember long evenings of sitting with my family, dictionary in hand, attempting to connect and make jokes and ask questions about their Mayan history and culture.

“In particular, I remember my host mom regaling us with our town’s many ghost stories, waving her hands wildly and raising her voice, causing my little host sisters to dissolve into fits of giggles. My first days in Guatemala were really defined by gratitude and appreciation of the simplicity and intimacy of daily life.”

Then it was time to get to work. Preston’s main role was to help school principals, teachers and government representatives help implement Guatemala’s plan to improve health and hygiene among students. The work was primarily with adults, but Preston sought out opportunities to spend time with kids by, like Galioto, helping out at camps.

Preston said her favorite memory was from an activity where girls created “self-esteem shields.” They divided a piece of cardboard into sections where each could draw something they had pride in about themselves, and about their goals.

“Watching these soon-to-be young women talk animatedly for the first time about who they wanted to be when they grow up would inspire just about anyone, but absolutely kept me grounded in my commitment to service,” she said. Preston has watched local leaders embrace the Healthy Schools plan, devoting more resources to it and measuring its success.

“I can’t necessarily say I can give you the percent in-crease of students who have improved their hand-washing techniques, but what I can tell you is that the climate and attitude surrounding health and hygiene has changed drastically amongst key community leaders,” she said. “They were aware of the strategy; however, they had very little understanding or interest in how to implement it. Now, schools are implementing small community projects and providing feedback and evidence of their successes.”

The experience has also had a lasting impact on Preston, making her “tougher, yet so much more humble and compassionate.”

“Navigating cross-cultural differences, understanding and negotiating differences in work style, and understanding Guatemalan professional and personal relationships are significantly more subtle and indirect than struggling with scarce resources, and can really be just as challenging personally and emotionally,” she said.

Preston sees in herself an improved ability to lead, particularly among people from backgrounds dramatically different from her own. But she said she hasn’t lost sight of the focus.

“These new strengths are deeply based in a new sense of humility and compassion for people and their individual struggles,” she said.

Preston noted that President Kennedy’s words in establishing the Peace Corps are read to volunteers at a ceremony marking the end of their service.

“So much of what the Peace Corps is this unbounded inspiration and optimism of American citizens to improve the world, and it’s a beautiful moment,” she said.

Story Written by Tom Kertscher