Charleston Farmhouse

The farmhouse is located in the Sussex countryside, set within the Sussex Downs, and one mile from Firle. The farmhouse is “large and unpretentious;” inside there was plenty of space for studios and rooms for guests. Outside of the house was a country landscape with a garden of which Vanessa Bell became invested in reviving and became the subject of many of her paintings (Naylor 138). “The red tiled roof, generous in scale, connotes warmth and protection. A farm pond in front of the house expresses a sense of informality and ease. The face of the house is simply configured, with a symmetrical arrangement of windows and central door. Though informal, it is proportionate and ordered. Attached to the house is a brick and flint wall which encloses the garden, lying to the north” (Hancock, Charleston and Monk’s House 59).

Virginia Woolf to Vanessa Bell

Carbis Bay, Cornwall, 24 September 1916

“It is very exciting to think that you may get Charleston. I hope you will. Leonard says there are certainly 8 bedrooms, probably more, and very good ones, two big sitting rooms on the ground floor and one small one; and very good large rooms on the first floor. He says the garden could be made lovely – there are fruit trees, and vegetables, and a most charming walk under trees. The only drawbacks seemed to be that there is cold water, and no hot, in the bathroom; not a very nice w.c. and a cesspool in the tennis court… Whatever you may say, I think the country there is superb to live in – I always want to come back again, and one never feels it dull, but then, not being an artist, my feelings are not to be considered ha! ha! … Please write soon and say what happens. I’m sure, if you get Charleston, you’ll end by buying it forever. If you lived there, you could make it absolutely divine.”

In September 1916, during the First World War, Vanessa Bell moved into the Charleston home with Duncan Grant, David (Bunny) Garnett, and Grant’s dog, Henry. Charleston became a significant home to Vanessa Bell’s two sons by Clive Bell, Julian and Quentin (Hancock, Charleston and Monk’s House 7). The Bloomsbury circle spent their time traveling to the various houses that members and their friends owned. They spent their time at the Charleston house throughout the year, and together with the Bloomsbury Group, as well as other affiliations, mainly stayed there in the summer.

David Garnett, The Flowers of the Forest, 1955

“…The actual move which followed was not so easy. Charleston had to be furnished and made habitable; the children, servants, and ducks had to be moved from Wissett, to say nothing of the easels, scores of canvases, boxes of paints, packing cases of books and a sack of globe artichoke suckers… At first there was an acute shortage of furniture and for some weeks Duncan and I had to sleep on the floor, owing to the lack of beds. For a long while several of the rooms remained empty and unused. Then some furniture was brought down from 46 Gordon Square, other pieces were bought in Lewes and these with rare exceptions were astounding objects, bargains which attracted Duncan or Vanessa because of their strange shapes and low prices… Both Duncan and Vanessa appeared to believe that the inherent horror of any badly designed and constructed pieces of furniture could be banished forever by decoration. The strange blend of hideous objects of furniture, pained with delightful works of art, gives to the rooms at Charleston a character which is unique and astonishing…” (Naylor 141).

Angelica Bell’s Birth

On Christmas Day 1918, Vanessa Bell gave birth to her daughter by Duncan Grant, Angelica, at the Charleston home. David Garnett (Bunny) wrote about the event in his letter to Constance Garnett with interesting detail of the Bloomsbury members present:

“Dearest Mother, Vanessa had a daughter born at 2 a.m. this morning, so I am very glad I was here. It is a queer little creature, very lonely and full of independent life. I went for the doctor about nine and sat up till it was over and then was able to have a look at it. It weighed seven and a half pounds, being put in a cardboard box on the kitchen scales. Clive is very glad it is a girl; so will Virginia be for she thinks highly of her own sex. Vanessa doesn’t and is probably rather disappointed. It is a curious emotional experience waiting for someone else’s child to be born” (Naylor 147).

Virginia Woolf wrote to Violet Dickinson about her meeting her new niece for the first time, and describes the Charleston Farmhouse in its progress:

“…I saw my new niece, Angelica, the other day; very lovely with vast blue eyes, and long fingers. Nessa presides over the most astonishing menage; Belgian hares, governesses, children, gardens, hens, ducks, and paiting all the time, till every inch of the house is a different colour…” (Naylor 147).

Artists and Writers: Works Completed

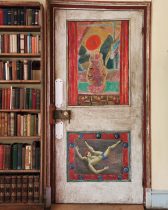

Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant spent the majority of their time painting and using their artistic ability to decorate the home. Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant designed the interior of the house “to create the impression of stepping inside the frame of a painting – an immersion into a three-dimensional Post-Impressionist world” (Hancock, Charleston and Monk’s House 62). Clive Bell worked on The New Renaissance during his visits. Maynard Keynes’s The Economic Consequences of the Peace was written at Charleston and published in 1919. Roger Fry helped design and build the studio, as well as create the garden with Bell.

David Garnett, The Flowers of the Forest, 1955

“…Charleston was at first a rambling old farmhouse, full of badly planned passages and small rooms. There was, on the garden side, a long cool dairy room with solid slate slabs round the walls to set the shallow pans of milk for creaming; on the way to it was a pantry and another larder or a stillroom with a slatted door. Slowly the house took on another, but equally living character. One after another, the rooms were decorated and altered almost out of recognition as the bodies of the saved are said to be glorified after the resurrection. Duncan painted many of the doors with pictures on the panels and with decorative borders round the frames. In every leisure moment he was at work… Duncan, like a sailor was always quietly occupied with some task of his own investment. ‘Creative activity was his passion; he was never satisfied with what he had ready-made; he longed to make something new.’ Those words written of Tchehov were equally true of Duncan… In his schemes Duncan was always seconded by Vanessa; they painted together in harmony, perfectly happy while they were at work and rarely resting from it. Thus Charleston was transformed” (Naylor 144).

Virginia wrote in her diary during her stay at Charleston and captures the essence of the home as well as those who resided in it:

Virginia Woolf’s diary

Friday, 2 November 1917

“…Yesterday it rained all day, so I sat in: writing about Aksakoff in the morning; sitting in the Studio after luncheon. Duncan painted a table, and Nessa copied a Giotto… They are very large in effect, these painters; very little self-conscious; they have smooth broad spaces in their minds where I am all prickles and promontories. Nevertheless to my thinking few people have a more vigorous grasp or a more direct pounce than Nessa. Two little boys with very attractive minds keep her in exercise. I like the feeling that she gives of a whole nature in use. In working order I mean; living practically, not an amateur, as Duncan and Bunny [David Garnett] both to some extent are of course. I suppose this is the effect of children and of responsibility, but always remember it in her…” (Naylor 142).

Years later, Woolf records another stay at the Charleston home, illustrating every detail in how Vanessa Bell, Duncan Grant, Roger Fry and others operated within the house as artists. While this chapter of her diary contrasts in tone from the previous of 1917, Woolf suggests that these artists differed from the writers of the Bloomsbury Group and invested the majority of their time to their artistic vocations.

Virginia Woolf’s Diary

Monday 6 August 1923

“We went over to Charleston yesterday. Although thinking quite well of ourselves, we were not well recieved by the painters. There sat like assiduous children at task in a bedroom – Roger, Nessa, & Duncan; Roger on chair in foreground; Nessa on sofa, Duncan on bed. In front of them was one jar of flowers, & one arrangement of still life. Roger was picking out his blue flower very brightly. For some reason, the talk was not entirely congenial. I suspect myself of pertness and so on. Clive was sitting in the drawing room window reading Dryden… Charleston is as usual. One hears Clive shouting in the garden before one arrives. Nessa emerges from a great variegated quilt of asters and artichokes; not very cordial; a little absent-minded. Clive bursts out of his shirt; sits square in his chair and bubbles. Then Duncan drifts in, also vague, absent-minded, and incredibly wrapped round with yellow waistcoats, spotted ties, and old blue stained painting jackets. His trousers have to be hitched up constantly. He rumples his hair. However, I can’t help thinking that we grow in cordiality, instead of drifting out of sight. And why not stand on one’s own leg, and defy them, even in the matter of hats and chaircovers? Surely at the age of forty… As for Duncan he requires, I think, peace for painting. He would like it all settled one way or the other. We saw a perfectly black rabbit, and a perfectly black cat, sitting on the road, with its tail out like a strap. ‘What they call an example of melanism’ said Clive – which amused me very much, and also made me like him…” (Naylor 152).

The Charleston Garden

Vanessa Bell’s approach to garden-making became a subject of a painter’s interpretation. She collaborated with Duncan Grant and mostly Roger Fry, “the overall design of the garden was conceived in collaboration with him [Fry] after the war” (Hancock, “Virginia Woolf and Gardens” 253). The garden became a studio en plein air [an inspirational context for study and observation] and a constant source of still lives and garden views for Grant and Bell. Bell’s daughter remembers that her mother had no need to go further than the garden to find the perfect motif; she could be seen hovering peaceably in front of her easel, her dress protected by a flimsy French apron, her feet in flat-heeled espadrilles, and on her head a broad-brimmed hat to shade her eyes from the glare. Her presence was betrayed by a smell of oil and turpentine. Cut flowers were brought from without to within, to decorate the house, as paintings verify, and as subjects for painting” (Hancock, Charleston and Monk’s House 99).

Bell wrote to her son, Julian, detailing the progress of the garden “from the promise of spring to full summer flowering.” In June, she wrote, “the garden is an overwhelming blaze of colour . . . pinks out in masses, roses. . . . By August, it is ‘a mass of flowers & as gay as possible . . . tobaccos & stocks smell strong in the evening. I often wander about in it at odd moments for the pleasure of the sights and smells.” A few weeks later, on a late summer day, Bell writes to Julian describing the atmosphere of the Charleston, “The house seems full of young people in very high spirits, laughing a great deal at their own jokes . . . lying about in the garden which is simply a dithering blaze of flowers and butterflies and apples” (Hancock, Charleston and Monk’s House 98).

The End of the Bloomsbury Group: Charleston Lives on

Duncan Grant lived at Charleston with Vanessa until she died in 1961, and continued to live there until his own death in 1978 (Hancock, Charleston and Monk’s House 7).

The Charleston Farmhouse opened in 1986, twenty-five years after the death of Vanessa Bell, under the custodianship of the Charleston Trust. The home is now a Museum, where people can tour the Bloomsbury home with offered tour guides to experience the history of the artist and writers who lived and stayed there. Charleston continues “to be a gathering place for artistic and literary pursuits, with two literary festivals each year and numerous related talks and events. Woolf and Bell’s intimate inhabitations are now cultural ‘theatres of memory” (Hancock, Charleston and Monk’s House 29).

Works Cited

Gillian Naylor, Bloomsbury: Its Artists, Authors and Designers, Little Brown, 1990.

Hancock, Nuala. “Virginia Woolf and Gardens.” The Edinburgh Companion to Virginia Woolf and the Arts, edited by Maggie Humm, Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, 2010, pp. 245–260. JSTOR, “http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3366/j.ctt1g0b0wh.19”>www.jstor.org/stable/10.3366/j.ctt1g0b0wh.19. Accessed 27 Apr. 2018.

Hancock, Nuala. Charleston and Monk’s House: The Intimate House Museums of Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell, Edinburgh University Press, 2012. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.3366/j.ctt3fgrqp. Accessed 20 Apr. 2018.

Richard Shone, The Art of Bloomsbury: Roger Fry, Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant, Princeton

UP, 1999.