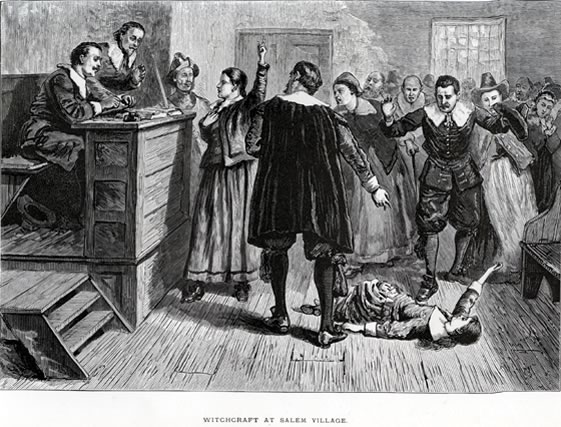

The image “Witchcraft at Salem Village,” created in 1876 by William A. Crafts, sheds light on a tragic and important time in early American history — the Salem Witch Trials of 1692. During the late 1600s, people living in the English colonies of New England, such as Massachusetts, were deeply religious. They lived in a theocracy, meaning they blended the church and state as a form of government. Church officials were involved in the government and could impose any laws they saw fit in their community. These laws – such as what they wore, how they acted, or what they could do in their day-to-day lives – were all strongly influenced by their religious beliefs and had an impact on how they responded to rising conflicts within their village.

Samuel Parris, the minister at the time, played a key role in all of this, as he would be one of the first to instigate the cause of what led to the Salem Witch Trials. He was the first to witness the events as they started to unfold, since it all began with his daughter, Betty Parris and niece, Abigail Williams. The two young girls were experiencing strange behaviors described as “uncontrollable outbursts” and screaming in his household. These acts were later diagnosed as “bewitchment” by the doctors and were further reinforced by the minister himself.

As the Puritans strongly believed in God – and that the Devil could grant “witches” the power to harm others – this was not surprising. This belief fueled the panic that spread throughout the town as more and more girls started to experience the same symptoms, and many were accused of witchcraft. This set off the numerous trials, imprisonments, and executions that took place.

The image shows us one of the trials that took place in the courtroom. You can see a young girl on the floor, described as “afflicted,” as she was supposedly being harmed by the spirit of a witch. Standing before the judges is a woman who was accused of witchcraft, holding her hand over her heart claiming to be innocent.4 Even though this woman was given the opportunity to stand before a trial to claim her innocence, the system was so deeply flawed that she had little to no chance of proving it.

The way in which they “proved” someone was a witch back then is very different from how we find evidence today. One of the main kinds of proof they were allowed to testify with was described as “spectral evidence,” where the girls claimed they could see the spirit of the accused person hurting them in their dreams or visions. This was seen as evidence even though that person was somewhere else and there was no physical proof of this. They would even allow things that people heard from others, “hearsay” as evidence, further reinforcing how unfair the legal proceedings were at the time.

This all resulted in over 200 accusations, with 20 men and women being wrongfully convicted and executed. The image reminds us of the anguish that the victims had to endure and the power that the accusers and judges held over them. It shows us the need for a fair legal system – one that protects the rights of individuals and ensures that justice is based on evidence, not unrealistic things such as superstition.

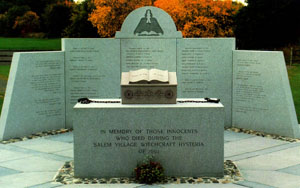

Today, Salem, Massachusetts, exhibits many memorials, such as the Salem Witch Trials Memorial, with the names of those executed engraved in stones, and the Proctor’s Ledge Memorial, located at the execution site. These all serve as places for reflection and remembrance.

Footnotes

[1] Hubbard, Cheryl. “Haunted Happenings and Hocus Pocus: Memorialization of the Salem Witch Trials–Is Salem Doing Enough?” The Pomegranate 23, no. 1–2 (December 31, 2021): 166–85. doi:10.1558/pome.21358.

[2] Latner, Richard. “‘Here Are No Newters’: Witchcraft and Religious Discord in Salem Village and Andover.” The New England Quarterly 79, no. 1 (2006): 92–122. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20474413.

[3] NIEHOFF, LEN. “Proof at the Salem Witch Trials.” Litigation 47, no. 1 (2020): 21–25. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27042154.

[4] Salem witch trials: Images. Accessed April 30, 2025. https://salem.lib.virginia.edu/generic.html.