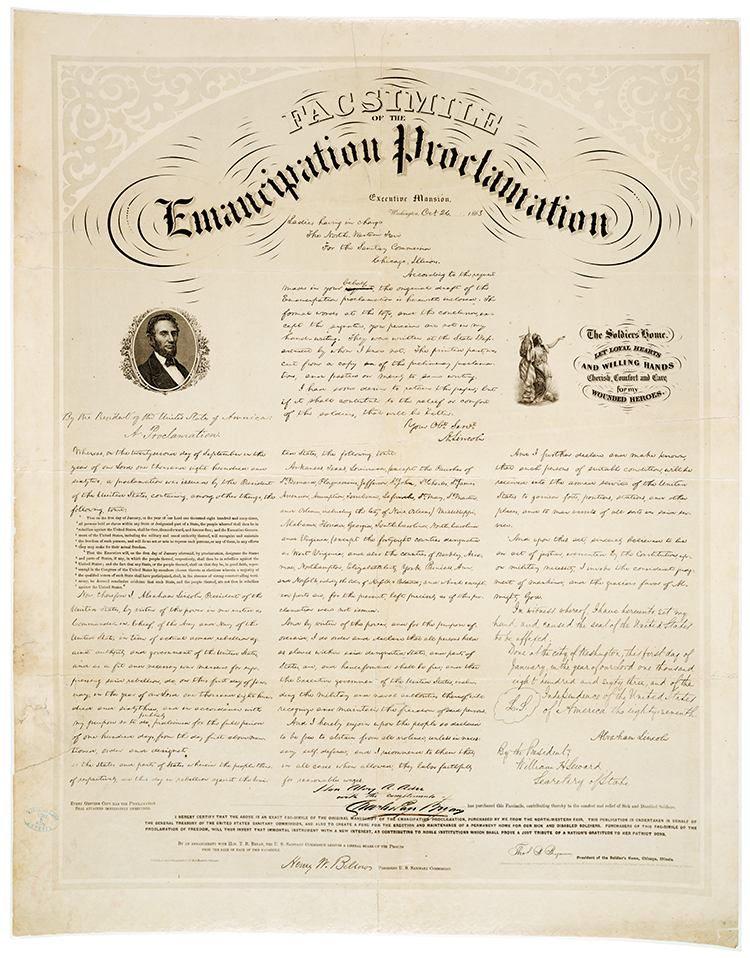

If someone told you that there was a document during the civil war that actually ended slavery but also at the same time did not technically fully end slavery, there is a high chance you would be a little confused or ask yourself: well which is it? did it end slavery? or did it not? Surprisingly, the answer is actually both! The Emancipation Proclamation, issued by President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, was one of the most important documents in American history. Even though it didn’t immediately free all enslaved people, it marked a critical shift in the Civil War and the nation’s stance on slavery. This executive order declared that “…the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free” [1]. You can view the full transcript of the Proclamation here.

Understanding the historical moment when this was written helps us appreciate its significance. At the time, the United States was two years into the Civil War. The war began after some southern states withdrew from the Union, forming the Confederate States of America( those states included Florida, Texas, the Carolinas, Alabama among others, Union states vs Confederate states) in response to the election of Abraham Lincoln, who opposed the expansion of slavery into new territories which is something that the confederates were rooting for. The conflict not only decided the fate of slavery but also reshaped the whole nation and led to the Reconstruction era, which attempted to integrate formerly enslaved people and the southern states back into the Union. Skipping ahead, the Civil War ended with the goal which was the preservation of the Union and led to significant changes in America, including the abolition of slavery.

However, there were many conflicts within the war that were completely unrelated to the actual fighting going on at the time but rather the constitutionality of the Proclamation and the motives behind it. Drawing from Sanford Levinson’s analysis in his lecture, he suggests that while the proclamation is praised for its moral stance, its selection and focus on the confederate states raised many eyebrows on whether it was truly a humanitarian act rather than just a military tactic in order to gain an advantage. Levinson notes, “It declares slaves to be free in territories of the secessionist states that were not yet under federal control; it left untouched the status of slaves not only in the four slave states that had remained within the Union—Maryland, Delaware, Kentucky, and Missouri—but also even those parts of the ostensibly secessionist states that had been brought under Union control” [2]. For this reason alone, people began to question whether this act was truly constitutional or not and whether this was nothing more than just a tactic to take away manpower from the confederacy.

Sanford Levinson was not the only scholar to doubt President Lincoln’s true intentions behind the Proclamation, in fact he was only one of many. Another writer by the name of Burrus M. Carnahan explores in depth how the Emancipation Proclamation was a strategic move by President Lincoln in his book, “Act of Justice” chapter 8, and reveals its role not just in altering the course of the war but also in how it was perceived by the Confederacy. Carnahan highlights the strong backlash from Confederate leaders like Jefferson Davis, who strongly criticized the Proclamation’s implications. Carnahan writes, “Davis charged that this language, by declaring that the United States would do nothing to suppress a slave insurrection, no matter how bloody it became, was a direct incitement for slaves to attack their masters indiscriminately”[3]. According to Davis, the Proclamation was a deliberate incitement, encouraging slaves to rise up against their owners, thus serving as a military strategy to destabilize the Southern states internally. This accusation underscores the dual nature of the Proclamation as both a beacon of hope for abolition and a calculated tactic to weaken the Confederate war effort by sowing chaos and fear among its population.

A counter to what most critics have been arguing can be seen through Henry L. Chambers Jr.’s article about the Emancipation proclamation. He offers a compelling legal defense by highlighting how Lincoln’s actions were firmly rooted in constitutional authority, particularly under the Take Care Clause which in simple terms, states that the president has a duty to fulfill and enforce all laws of the constitution. Chambers argues that the Proclamation was not just an exercise of wartime power but a fulfillment of Lincoln’s constitutional obligation to ensure that the laws are followed strictly and without deviation. He states, “Though specific laws may have applied to a discrete group of slaves or a particular swath of the United States, when taken as a whole, Civil War legislation passed before the Emancipation Proclamation was issued makes clear that Congress was willing to move toward emancipation as a war measure, and more generally”[4]. Chamber’s view illustrates that the Emancipation Proclamation was actually in alignment with prior legislative actions by Congress, which had already laid the groundwork for the emancipation of the slaves, which therefore makes the Proclamation constitutional.

BIOGRAPHY:

[1]National Archives, “The Emancipation Proclamation: Transcript,” National Archives and Records Administration, https://www.archives.gov/exhibits/featured-documents/emancipation-proclamation/transcript.html.

[2] Sanford Levinson, The David C. Baum Memorial Lecture: Was the Emancipation Proclamation Constitutional – Do We/Should We Care What the Answer Is, University of Illinois Law Review, vol. 2001, no. 5 (2001): [pg.1139]

[3] Burrus M. Carnahan, “The Proclamation as a Weapon of War,” in Act of Justice: Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation and the Law of War, 127, University Press of Kentucky, 2007.

[4] Henry L. Chambers Jr., “Lincoln, the Emancipation Proclamation, and Executive Power,” Maryland Law Review 73, no. 1 (2013): [104].