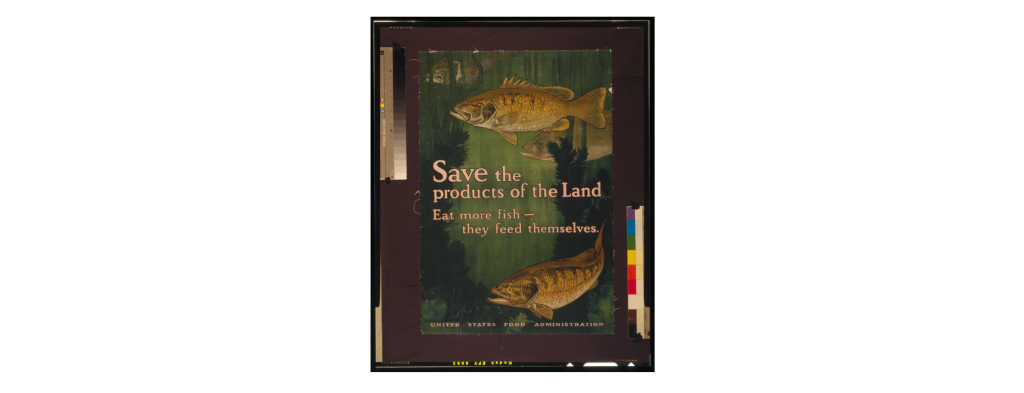

This campaign poster illustrates a school of fish swimming effortlessly in a body of water, contrasting the tensions of the war on land.

Charles Livingston Bull’s campaign poster “Save the products of the land – Eat more fish – they feed themselves” was created between 1917 to 1918 for the United States Food Administration (USFA). This was during World War I, which was a critical time for food resources as most resources were being saved or created for war efforts abroad. For food resources specifically, the USFA that was led by 31st President Herbert Hoover urged Americans at home to change their consumption habits by conserving meat products like poultry and beef. These land-based resources required the consumption of food resources, which would be better allocated for human use or towards poultry and beef products that were being sent to troops abroad. As the poster’s text claims, eating fish is the best option as fish can survive without consuming human resources. Combined with the illustration, the poster suggests a message that is difficult to argue and thus easy to follow. Since fish can support themselves, Americans at home should participate in a fish diet so that troops abroad can benefit from the increased availability in American meat products.

The U.S. government pushed this campaign to suggest one way that Americans can show patriotism during the time of war. Most posters, such as Bull’s, targets daily aspects of American life as a way to broaden their audience and impact all members of a household. In his work, Tanfer Emin Tunc highlights how the USFA considered women and organizations in the following, “By using poster and grass-roots campaigns to appeal to their activities in the private sphere of the household (as mothers and wives who toiled in gardens and kitchens) and their pre-existing activism in the public sphere (as members of Progressive women’s groups, clubs, and networks that fought for temperance and suffrage)” (Tunc, 195)1. By using the method of highlighting private life, Americans of all demographics had the opportunity to relate and contribute to mass food conservation. During a time where American women were beginning to join the workforce, the fish diet campaign impacted women who prepared meals in their homes, as well as women who worked in agriculture. For American society overall, Bull’s message impacted the food production industry when it marketed the fish diet as an act of patriotism.

The push towards fish diets also benefited groups beyond the USFA and U.S. government. In Ross Coen’s work, he notes the following in regard to the fishing industry, “The shipment represented not only a patriotic gesture, but also a savvy marketing ploy” (Coen, 459)2. By this, Coen means that the fishing industry expanded in the Pacific Northwest and resulted in an increase in profit and consumers. Fish products like salmon could be canned and easily distributed to locations where food sources are needed, such as the U.S. and abroad. The patriotic duty to consume fish created a new flourishing business that was receiving increased support. The U.S. government even got involved, as shown in the following, “To increase the supply of fish the Food Administration persuaded the War Department to permit the use of traps in hitherto unexploited waters. The Navy Department agreed to allow fishermen to enter certain zones otherwise barred because of the submarine menace” (Wright, 82)3. These measures ensured that the poster’s message could be followed through, as the U.S. military backed the daily operations related to the fishing industry. With the expansion of fishing locations, the variety of fish would also increase. This is illustrated in Bull’s poster, as each fish has its own unique look. Even as Americans reduced their diet to fish, their options of fish were not limited.

Ultimately, Bull’s campaign poster expressed a message that was supported by the USFA, the U.S. military, and eventually the American population. Troops fighting abroad could receive more food products like meat as a result of food conservation acts done by Americans at home. During World War I, patriotism became associated to the food industry, which was ran by women entering the workforce and Americans who participated in food diets. Self-sufficiency became a common theme for this era, which is a characteristic that Bull highlights in his poster as he pushed the fish diet.

Bibliography

2Coen, Ross. “Fish Is a Fighting Food: North American Canned Salmon and the First World War.” Northern Review, no. 44 (January 1, 2017): 457–64. doi:10.22584/nr44.2017.020.

1Tunc, Tanfer Emin. “Less Sugar, More Warships: Food as American Propaganda in the First World War.” War in History 19, no. 2 (2012): 193–216. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26098429.

3Wright, Almon R. “World War Food Controls and Archival Sources for Their Study.” Agricultural History 15, no. 2 (1941): 72–83. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3739653.