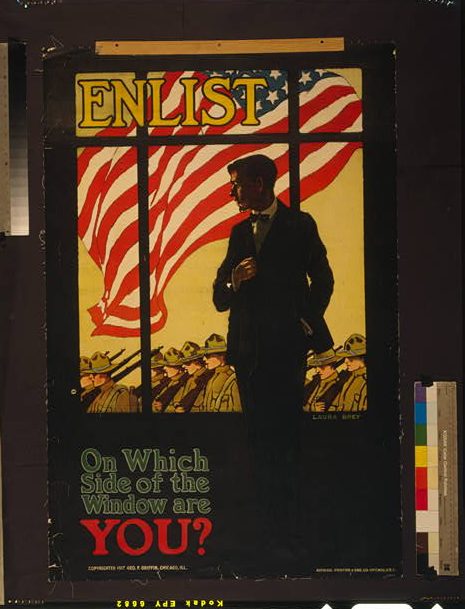

Both the U.S. government and private organizations conducted large scale propaganda in order to build support for the war, most notably in Laura Brey’s 1917 recruitment poster [4] “Enlist: On Which Side of the Window Are You?” This image captures what is likely a pivotal moment in American history, a moment when patriotism, masculinity, and social responsibility were combined into one powerful image. Commissioned by the U.S. Army (the Committee on Public Information alias CPI) pursued to persuade men to volunteer and enlist even before the draft started. Brey’s poster is a symbol of the way that art and emotion were used to construct national identity during wartime.

At first glance, the poster is straightforward. A young man is standing indoors, looking through an oversized window at soldiers marching underneath a huge American flag. The word “ENLIST” sits boldly at the top of the image in yellow letters, and below the challenge is stated “On which side of the window are you?” This prompt elevates an observer to a participant by asking a question, the author demands the viewer to engage in thinking about avoiding risk and remaining a civilian, or risking it all to serve the nation being defended. Brey creates the image so that the viewer is in the same space as the civilian man. It becomes easy to see oneself standing where he stands. He is posed to heighten a sentiment of doubt and self examining which is something that encourages young men to confront their duty.

U.S. Marine Corps recruitment poster promoting travel and adventure, 1917

To grasp the implications of this poster, it is necessary to understand it within the context of American society in 1917. At that point, the United States had recently declared war on Germany entering World War I, having maintained a neutral stance for years. Additionally, the country had a society that was hesitant to fight a European war. To ease this hesitancy, President Woodrow Wilson created the Commission on Public Information, which produced millions of posters, pamphlets and films in order to stir up a sense of patriotism, sense of duty and sense of morality. Historian Michelle Woods described these campaigns as shifting military service from “a government order” to “a personal appeal” a matter of character, allegiance, and moral order [1]. Even other posters such as this U.S. Marine Corps advertisement which promise travelling and adventure, also use emotion and hope to recruit young men which highlight this excitement and manhood as reasons to serve. Brey’s poster represents this type of campaign [5]. Rather than depict battles or threats of enemy approach, it relies on evoking the emotional conscience of its audience by engaging audiences through conversation about what it meant to be a man, and citizen required personal engagement.

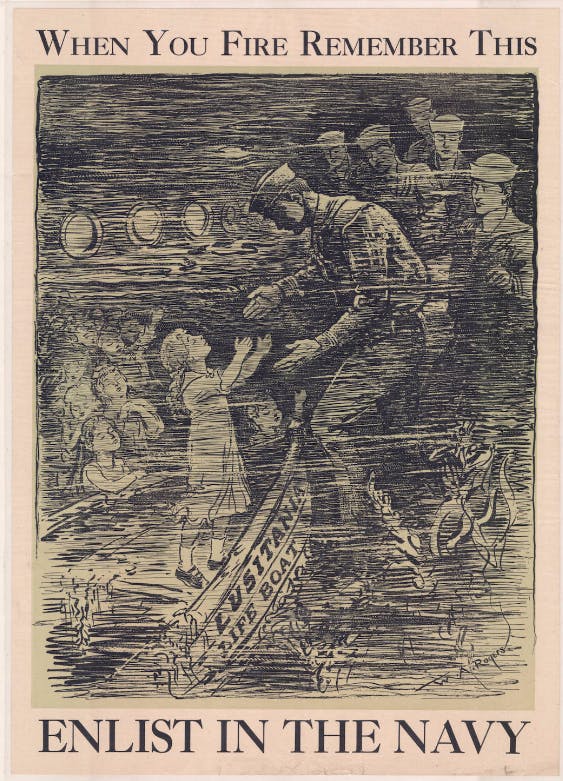

U.S. Navy recruitment poster invoking the Lusitania tragedy to inspire enlistment, 1917

Later on, propaganda scholar Harold D. Lasswell changed what propaganda was as “the management of collective attitude by the manipulation of significant symbols.” [2] The symbols in this poster include the flag, the soldiers, and the window which all symbolize different meanings. The flag signifies unity with sacrifice, the soldiers embody courage and commitment to each other, and the window separates the horizontal, active agent from the voyeur, simply watching through the glass pane. The design takes advantage of contrast, the warm sun and movement of the outside world, shadows and a feeling of unwanted stasis to the interior. This visual separation is an emotional analogue to the moral separation between supporting one’s duty to serve and doing nothing. Brey is also using perspective as a means of increasing psychological pressure. This is seen by the man’s gaze, as he looks toward the marching troops, creating a sense of exclusion that is resolved only by enlisting. Furthermore, other posters of the war, used a strong emotional imagery to have an influence in society. For instance, this navy recruitment [6] poster reminds Americans of the 1915 disaster in Lusitania as is makes use of guilt and empathy as a motive.

Art historian Sarah F. Price observes that posters created during World War I were created for the purpose of presenting enlistment as both patriotic and socially obligatory [3]. Brey’s work holds emotional sway because it subtly employs guilt and aspiration. The image asks one, are you in the space of the safe spectators, or are you among the enlisted men in uniform? Is the question “On which side of the window are you?” implying that neutrality is shameful, and that being outside of the act is a failing? In contracting the civilian to be educated, middle class and respectable, Brey counters the notion that war is for the poor or poor skilled. Instead, all men no matter the circumstance are called. This type of moral and social pressure is indicative of a larger war culture in which masculinity and public service, even self sacrifice were linked.

Brey’s poster ultimately demonstrates how visual art became a persuasive tool in the early twentieth century. The U.S. government and artists similarly understood that it could prove more effective to persuade the public through emotion rather than rational thought. What made the poster so effective was its transformation of enlisted service from a state’s command to an individual’s moral conscience. The poster blurred the lines of private life and betraying duty while asking Americans to determine their worth through patriotic action.

Even today’s “Enlist: On Which Side of the Window Are You?” remains a robust example of a propaganda not only framing public opinion but also shaping a national identity. Its simplicity illustrated that during World War I, Americans were encouraged to view themselves as defining who they were through duty and belonging, and as though self sacrifice was necessary to maintain their freedom. Brey captured not only the moral urgency of a nation at war but the lasting effects of visual persuasion in his simple question.

Works Cited:

1. Woods, M. “Personal Appeal.” Historical Perspectives (2012). Link

2. Lasswell, Harold D. “The Theory of Political Propaganda.” The American Political Science Review 21, no. 3 (August 1927): 627–631. Link

3. Price, S. F. “3B3: WWI Propaganda Poster Fluidity.” (2016). Link

4. Brey, Laura. “Enlist on Which Side of the Window Are You? /.” Home, January 1, 1970. Link

5. Lederle, Cheryl. “Analyzing Propaganda’s Role in World War I: Teaching with the Library.” The Library of Congress, May 10, 2018. Link