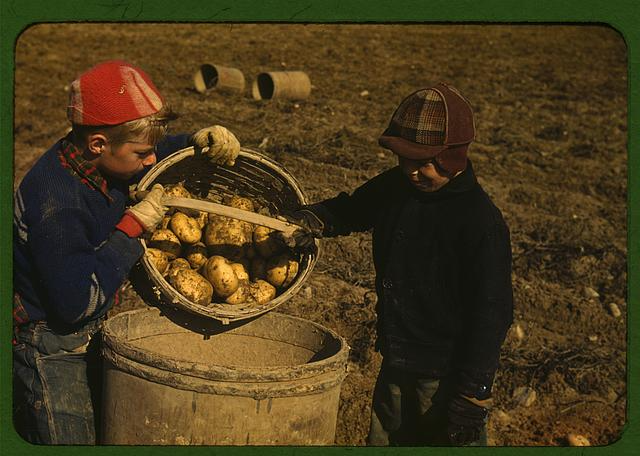

In this picture from October 1940, a couple of school-aged children gather potatoes on a large farm in Caribou, Maine. The caption, “Schools do not open until the potatoes are harvested,” comes from Farm Security Administration (FSA) photographer Jack Delano, who traveled the country documenting rural life during the Depression era of the United States. [1] The image belongs to the FSA/OWI (Office of the War Information) collection, on of the major documentary photography projects of the twentieth century. Shot on Kodachrome, the slide’s russet earth makes the farm feel immediate and lived-in. At the same time, the vivid color brings attention to the central issue, children performing a full commercial harvest.

Delano’s photograph functions as both documentation and argument. As part of New Deal documentary efforts, FSA photographers were tasked with showing Americans how ordinary people lived, labored, and survived. [2] In northern Maine, this meant potatoes. Aroostook County was a major center of New England agriculture, and the fall “potato recess” shaped community life. Local schools often delayed opening or temporarily closed so children could help with the harvest. [3] Delano’s caption captures this local practice in a single sentence.

For contemporary viewers, the picture reveals the rhythms of a regional farm economy that depended on the labor of entire families, including children. Cody Miller’s study of New England farm culture (1870-1905) shows that agricultural households valued children’s labor not only economically but also morally, as part of a family ethic of usefulness, thrift, and mutual obligation. [4] These cultural expectations persisted well into the twentieth century in places like Aroostook, even as agriculture mechanized unevenly and markets expanded. [5]

The image shows freshly turned rows, suggesting recent digging by a horse-drawn or tractor-drawn harvester. This would allow potatoes to rest on the soil surface for children to pick and sort into barrels or baskets, a common practice before fully mechanized harvesters became widespread. [6] The horizon is not visible but in the background, many rows are present and covers the whole image. Gives the illusion that the work is endless and repetitive. The children’s layered clothing indicates that the October air was cold and crisp, underscoring the long, physically demanding days.

Delano’s scene avoids dramatizing injury or hardship, making his perspective observational rather than accusatory. Yet the caption prompts the viewer to consider the implications of schooling giving way to seasonal labor. According to the textbook, late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century child workers often missed school and experienced high accident rates. [7] Agricultural work, however, remained exempt from many child-labor protections, reinforcing a cultural distinction between “family farm work” and industrial labor. As Jennifer Terry argues, this distinction helped normalize children’s farm labor even as industrial child labor declined. [8]

The image captures a transitional moment in history. Maine agriculture in the mid-twentieth century stood between tradition and modernization, as larger operations, regional processors, and shifting markets reshaped farm labor. [9] At the same time, the Great Depression and New Deal created a broadened federal interest in documenting everyday American life. Delano’s photograph shows how national policy, regional economics, and local family strategies intersected on the ground.

Finally, the photograph illustrates a community consensus about youth, work, and education that may feel unfamiliar today. The children’s presence signals both necessity (the harvest needed to be completed before frost) and belonging (this was the family’s and town’s work). This combination of pride and risk captures the contradictions of the era. The same qualities rural communities celebrated as character-building could also limit schooling and expose children to hazards. [10],[11] Delano neither condemns nor idealizes; he simply records the moment.

Footnotes:

-

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA/OWI Collection, Jack Delano, “Children gathering potatoes on a large farm, vicinity of Caribou, Aroostook County, Me. Schools do not open until the potatoes are harvested,” October 1940, color slide, LC-DIG-fsac-1a33844.

-

Library of Congress, “Bound for Glory: America in Color—Exhibition Items,” entry for LC-DIG-fsac-1a33844.

-

Jane E. Radcliffe, “Perspectives on Children in Maine’s Canning Industry, 1900–1950,” Maine History24, no. 2 (1985): 102–118.

-

Cody P. Miller, “‘The Farmer’s Family Must Find Compensation in Something Less Tangible, Less Material’: Culture and Agriculture in Maine and New England, 1870–1905,” Maine History 49, no. 2 (2015): 150–175.

-

Robert Wescott, The Transformation of Farming in Maine, 1940–1985 (Orono: University of Maine Press, 2015).

- Edward F. Johnston, “A History of Potatoes in Aroostook County,” The County, August 25, 2009, https://thecounty.me/2009/08/25/living/a-history-of-potatoes-in-aroostook-county/.

-

David E. Shi, America: A Narrative History, Brief Twelfth Edition, vol. 2 (New York: W.W. Norton, 2022).

-

Jennifer R. Terry, A Century of Denying Child Labor in America (PhD diss., University of California, 2018).

-

Radcliffe, “Perspectives on Children in Maine’s Canning Industry,” 102–118.

-

David E. Shi, America: A Narrative History, Brief Twelfth Edition, vol. 2 (New York: W.W. Norton, 2022).

-

Jennifer R. Terry, A Century of Denying Child Labor in America (PhD diss., University of California, 2018).