The American Revolution provided a false hope for those of enslaved men and women. The author of the constitution, Thomas Jefferson, had wrote about the communal agreement of liberty and justice for all. In these words, many implications fell victim to the lack of specificity. To most, it was a call for eventual emancipation of such individuals trapped in servitude, while others used this as leverage based solely on the lack of recognition towards the black community and their role in a free world.[1] This idea had led to many individuals of color, free or not, to be under the unforgiving grasps of the white population during this time (picture).[2]

Many laws soon were introduced to this newly created country to help cement slavery for years to come. One of these laws was known as the fugitive slave act. The fugitive slave act was a law enacted by congress around the year 1793 which implied that state governments could ca pture and return escaped slaves if suspicious or even fitting a description, along with punish those who tried to aide in their escape.[3] As one can imagine, this was not greeted with open arms by the community of freed black men and women.[4] The

pture and return escaped slaves if suspicious or even fitting a description, along with punish those who tried to aide in their escape.[3] As one can imagine, this was not greeted with open arms by the community of freed black men and women.[4] The

ridicule for this act, by both men of color and whites, led to congress reinstating the act in 1850, only this time with more repercussions for the interference or disagreement of the act itself. One may wonder why this law was put into place to begin with, knowing how at this point northern states were already making progressive strides for freedom for all (not so  much equality). The answer to this is simple: fear (picture)[5]. At the time of this act, the United States government made a truce with southern states that they would not abolish slavery in the hopes that they remain a vital piece in fighting back against British forces.[6] After the revolutionary war, these southern states watched their northern states abolish slavery one by one, and through fear of losing their main source of revenue, they made a stand in any way they could.[7] Years of the fugitive slave act led to many individuals of color being enslaved even if they had been considered a free man their whole life.

much equality). The answer to this is simple: fear (picture)[5]. At the time of this act, the United States government made a truce with southern states that they would not abolish slavery in the hopes that they remain a vital piece in fighting back against British forces.[6] After the revolutionary war, these southern states watched their northern states abolish slavery one by one, and through fear of losing their main source of revenue, they made a stand in any way they could.[7] Years of the fugitive slave act led to many individuals of color being enslaved even if they had been considered a free man their whole life.

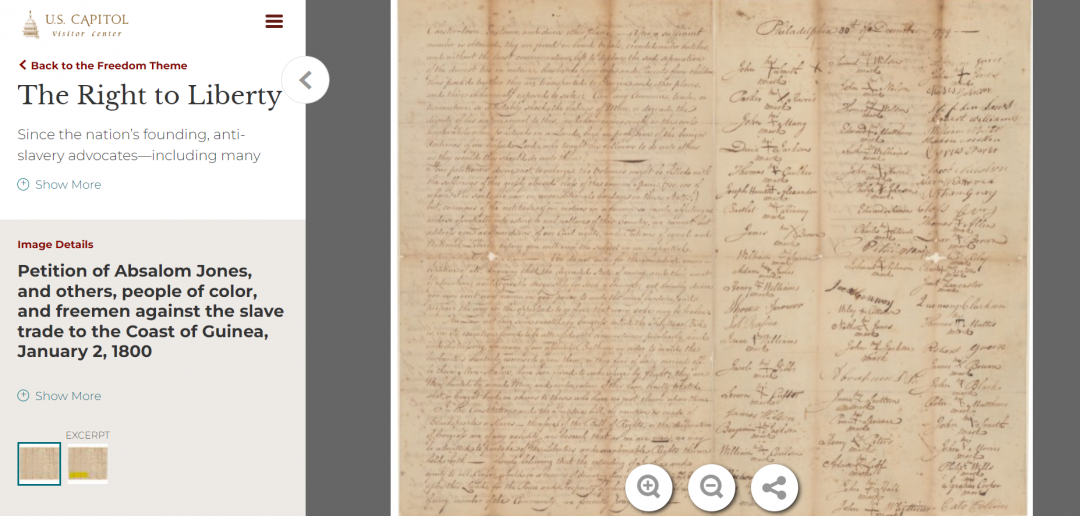

Absalom Jones (picture)[8] was a very highly regarded man of color for this time period. Jones was Americas first black priest, who was born into slavery.[9] Jones was self-educated through night school in Philadelphia. In this article, Jones describes how his life after slavery should not be potentially taken from him because of a cowardly attempt to continue the degradation of colored individuals.[10] By gathering more than 70 signatures, he was able to create a reasonable argument as to the fugitive slave act and its intent based off its cause. He argued that such act was placed before the black man as a way to continue slavery. This document was one of the only remaining petitions sent to the government originating from a black individual. Without hesitation Jones makes note that even though freedom is not so farfetched of an idea, the only limiting factors is those states whom of which refuse to acknowledge equality. He believed that even in progressive states it is hard to see his people enjoy the liberties given to that of his white counterparts.[11] Some of these rights included education and certain occupations. To sum up his whole argument, Absalom uses one of the most controversial writings to solidify his case: the constitution. Under the constitution, as forementioned, it failed to acknowledge the identity of black community, therefore calling for an undeniable reformation of how the societal standards are to be held.[12] Jones does an excellent job of outlining the importance of his stance, while he does not openly criticize the newly formed government, rather, calling for a hopeful change in how men of darker skin colors are to be handled.

individual. Without hesitation Jones makes note that even though freedom is not so farfetched of an idea, the only limiting factors is those states whom of which refuse to acknowledge equality. He believed that even in progressive states it is hard to see his people enjoy the liberties given to that of his white counterparts.[11] Some of these rights included education and certain occupations. To sum up his whole argument, Absalom uses one of the most controversial writings to solidify his case: the constitution. Under the constitution, as forementioned, it failed to acknowledge the identity of black community, therefore calling for an undeniable reformation of how the societal standards are to be held.[12] Jones does an excellent job of outlining the importance of his stance, while he does not openly criticize the newly formed government, rather, calling for a hopeful change in how men of darker skin colors are to be handled.

In the link below, please feel free to examine the document I have discussed. The link shows you the document itself, and how valuable of a resource that it really was. To have 70 men of color at the time come together and fight for what they believe was right is truly special.

[1] Absalom, Jones. “Petition of Absalom Jones, and Others, People of Color, and Freemen against the Slave Trade to the Coast of Guinea, January 2, 1800.” U.S. Capitol Visitor Center. Accessed May 2, 2022. https://www.visitthecapitol.gov/exhibitions/artifact/petition-absalom-jones-and-others-people-color-and-freemen-against-slave-trade#:~:text=In%20this%20petition%2C%20Absalom%20Jones,the%201793%20Fugitive%20Slave%20Act.

[2] History.com Editors. “Fugitive Slave Acts.” History.com. A&E Television Networks, December 2, 2009. https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/fugitive-slave-acts#:~:text=Enacted%20by%20Congress%20in%201793,who%20aided%20in%20their%20flight.

[3] History.com Editors. “Fugitive Slave Acts.” History.com. A&E Television Networks, December 2, 2009. https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/fugitive-slave-acts#:~:text=Enacted%20by%20Congress%20in%201793,who%20aided%20in%20their%20flight.

[4] White, Deborah G., Mia Bay, and Waldo E. Martin. Freedom on My Mind: A History of African Americans, with Documents. Boston: Bedford/St. Martins, 2021.

[5] “Fugitive Slave Acts.” Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. Accessed May 2, 2022. https://www.britannica.com/event/Fugitive-Slave-Acts.

[6] History.com Editors. “Fugitive Slave Acts.” History.com. A&E Television Networks, December 2, 2009. https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/fugitive-slave-acts#:~:text=Enacted%20by%20Congress%20in%201793,who%20aided%20in%20their%20flight.

[7] White, Deborah G., Mia Bay, and Waldo E. Martin. Freedom on My Mind: A History of African Americans, with Documents. Boston: Bedford/St. Martins, 2021.

[8] “Blessed Absalom Jones – St. Martin-in-the-Fields.” www.stmartinec.org. Accessed May 2, 2022. https://www.stmartinec.org/blog/blessed-absalom-jones/.

[9] Duffy, Mark J, and Maribeth Kobza Betton. “Leadership Gallery.” Omeka RSS. Accessed May 2, 2022. https://episcopalarchives.org/church-awakens/exhibits/show/leadership/clergy/jones.

[10] Duffy, Mark J, and Maribeth Kobza Betton. “Leadership Gallery.” Omeka RSS. Accessed May 2, 2022. https://episcopalarchives.org/church-awakens/exhibits/show/leadership/clergy/jones.

[11] White, Deborah G., Mia Bay, and Waldo E. Martin. Freedom on My Mind: A History of African Americans, with Documents. Boston: Bedford/St. Martins, 2021.

[12] Absalom, Jones. “Petition of Absalom Jones, and Others, People of Color, and Freemen against the Slave Trade to the Coast of Guinea, January 2, 1800.” U.S. Capitol Visitor Center. Accessed May 2, 2022. https://www.visitthecapitol.gov/exhibitions/artifact/petition-absalom-jones-and-others-people-color-and-freemen-against-slave-trade#:~:text=In%20this%20petition%2C%20Absalom%20Jones,the%201793%20Fugitive%20Slave%20Act.