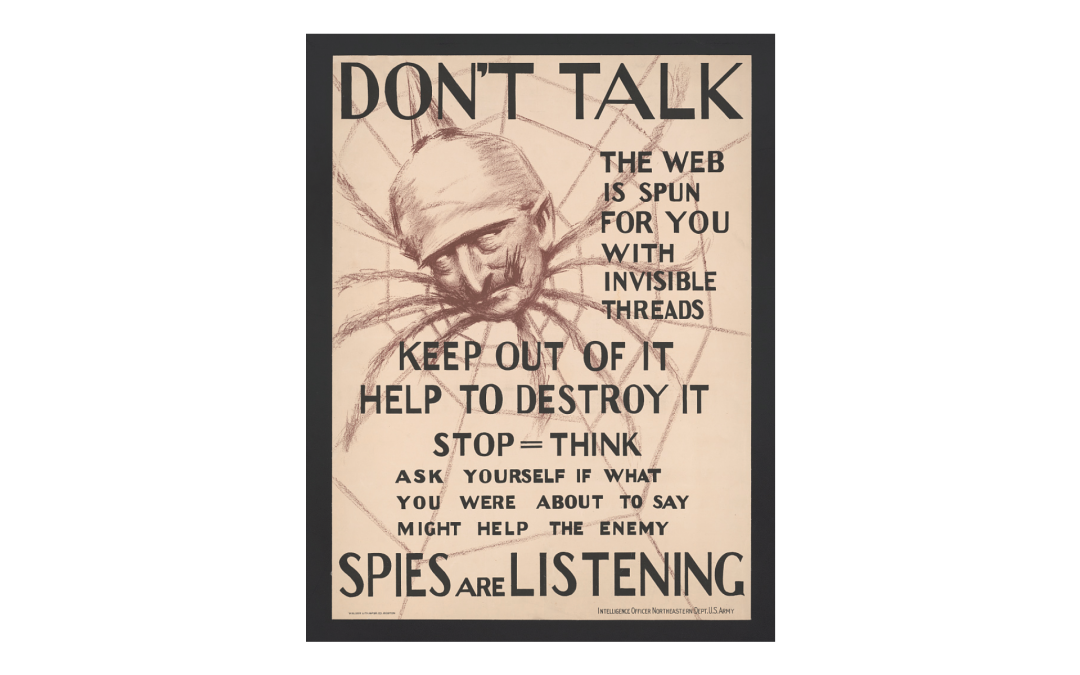

The year 1918 marked the final and most intense phase of the First World War, a moment when the U.S. government relied heavily on propaganda to mobilize the home front. One striking example is the poster that reads: “Don’t talk—the web is spun for you with invisible threads—spies are listening.” 1. This poster had been one which was produced by the Committee on Public Information (CPI), which had been one of the federal agencies responsible for affecting the overall public opinion that people held during the war. This poster had tried its best to urge Americans to aim to guard their conversation in order to avoid mentioning troop involvement in the war, as it had focused on preventing sharing any information that may cause aid to the enemy. The image depicts a crowned, menacing spider, symbolizing Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany, looming over a vast web. This image in specific is an incredibly visual image which can be seen as a metaphor that warns citizens that Germany’s reach was something that is widespread, covert, and dangerous, implying that even very simple remarks can threaten national security. For many museum visitors in this time period, the poster can be seen as something that exemplified the degree to which World War I had resulted in the blurred boundaries between civilian life as well as things like military responsibility, which had been something that encouraged everyday Americans to view silence as something very patriotic.

In order for one to fully understand the significance of this poster it is essential for them to understand the broader context that comes with World War. This had been a conflict which began in 1914 and lasted until 1918, the conflict involved more than thirty nations and required intense support and mobilization from many communities. Holger Afflerbach writes that “By dedicating the French nation anew to the fight, Clemenceau reunited the government and the people with the army in a common objective” (Afflerbach) 1. This insight illustrates that war is not simply a military struggle but also something that is a social and psychological struggle. For the United States in particular, when they entered the war, it faced the enormous task of unifying a reluctant and diverse population behind the war effort. Propaganda posters had a vital role when it comes to this particular mission. By being able to emphasize that even “casual comments” could result in the endangerment of our country, the CPI turned any casual comments into a fault against society, reinforcing the government’s need to maintain secrecy and loyalty.

The visual details of the poster highlight how the CPI used symbolism to evoke both fear and responsibility. The spider, an almost universally unsettling creature, communicates hidden danger and acts as a personification of the German enemy. Its crown identifies it specifically with Kaiser Wilhelm II, linking the threat directly to German leadership. The “invisible threads,” which can be easily spotted on the image, represent secret networks of espionage and eavesdropping, suggesting that conversations in homes, factories, and military bases were all vulnerable. Even the placement of the text itself, which is bold, direct, and commanding, results in more urgency being added. The language (“Don’t talk,” “Help destroy it”) is not something which persuades one gently, but rather in a direct manner. This is something which easily reflects the wartime expectation revolving around being good citizens that showcase obedience, restraint, and loyalty that remains unquestioned.

At the same time, the poster reflects the broader social pressures shaping American life during the war. Lea van Bergen, in The First World War and Health, explains how the conflict transformed public expectations of civilian behavior, including volunteerism and emotional resilience. She notes that “The First World War gave [the Red Cross] another opportunity to show their invaluable importance in times of armed conflict” (Bergen).1 This directly relates to the poster’s message: both the Red Cross campaigns and silence-about-secrets campaigns relied on citizens adopting new behavioral norms in the name of national defense. Support for the war can be seen in many various different forms, whether it be donating food, saving various resources, or, as this poster insists, taking control over one’s freedom of speech.

This expectation of civilian participation was not limited to the United States. As De-Valera N. Y. M. Botchway writes in Africa and the First World War, “Ordinary African men and women are largely invisible in the big narratives of the war… imperial powers attempted to marginalize the contribution of Africans and obscure the large degree to which they depended on the colonized Africans to fight the war.” 1The global scale of wartime mobilization helps explain the atmosphere of fear surrounding information leakage. Millions of people across continents were pulled into the war effort—voluntarily or not—and governments everywhere sought to control behavior, information, and loyalty. The “Don’t talk” poster is part of that broader story: the belief that every civilian action, no matter how small, mattered for the war’s outcome.

This CPI poster illustrates how much the government depended on patriotic silence as a way to promote unity during the war. The poster had aimed to turn regular everyday Americans into quiet, watchful watchers. It serves as a reminder of how propaganda can so easily influence civilian behavior and how the American experience during the war was dominated by worries about espionage, disloyalty, and loose talk.

Works Cited

- Afflerbach, Holger. The Purpose of the First World War: War Aims and Military Strategies. De Gruyter Oldenbourg, 2015. https://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/bitstream/handle/document/70608/ssoar-2015-afflerbach-The_Purpose_of_the_First.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y&lnkname=ssoar-2015-afflerbach-The_Purpose_of_the_First.pdf

- Botchway, De-Valera N. Y. M., and Kwame Osei Kwarteng, editors. Africa and the First World War: Remembrance, Memories and Representations After 100 Years. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2018. https://search.library.wisc.edu/catalog/9913310906902121

- Van Bergen, Lea, and Eric Vermetten, editors. The First World War and Health: Rethinking Resilience. Brill, 2020. https://research.ebsco.com/c/dq7v4l/search/details/mowp4wyikr?limiters=LB%3ATEIgQXJjKg%3D%3D%26TEIgSW50Kg%3D%3D%26TEIgU2VtKg%3D%3D%26TEIgV2FsKg%3D%3D%26TEIgVmFsKg%3D%3D&q=The%20First%20World%20War%20and%20Health&searchMode=all

- Walker Lithograph & Publishing Co. Don’t Talk, the Web Is Spun for You with Invisible Threads, Keep Out of It, Help to Destroy It—Spies Are Listening. Boston, 1918. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, https://www.loc.gov/resource/ppmsca.53575/