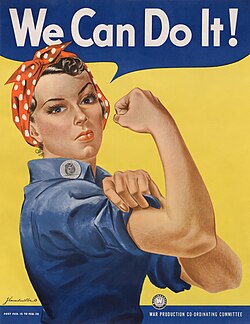

World War II brought historic changes when American women started working in large numbers for the first time. The war effort required women to take over manufacturing work at factories and shipyards and aircraft plants because male soldiers fought abroad. We Can Do It! The poster by J. Howard Miller is a symbol of the major changes women brought to the workforce during that time. The poster shows a confident woman wearing a blue work shirt and a red-and-white polka-dot bandanna, flexing her arm beneath the words “We Can Do It!”. At the time, Miller’s purpose was to motivate factory workers and boost morale inside Westinghouse plants. Yet over the decades, this brief wartime image has become one of the most enduring symbols of female strength and independence in American culture.¹

When the war began, the government launched huge campaigns to recruit women into the wartime industry. Propaganda posters, radio messages, and newspaper stories encouraged women to “do their part” by joining production lines. According to María Cristina Santana, wartime propaganda both empowered and constrained women. It invited them into the public sphere and paid employment, but it also presented that work as a temporary duty that would end when the war was won.² After 1945, many of these same campaigns were telling women to return home to domestic life. They wanted to reinforce older gender norms even after women had proven their capability in demanding jobs.

The poster captures that tension. When you first see the image it shows confidence and determination. Miller’s artistic choices show the tight framing, bright yellow background, and the gaze of the women makes her look powerful and optimistic. Her rolled-up sleeve and clenched fist turn ordinary factory work into a patriotic act. Yet as James Kimble and Lester Olson explain, the poster was never meant as a feminist message. In their study of the image’s visual rhetoric, they show that Westinghouse commissioned it simply to raise morale among existing employees for a two-week internal display. It was not meant to be for government recruitment and the woman portrayed was not called “Rosie the Riveter.”³ It was only decades later when Americans began to link the image with the broader cultural figure of “Rosie,” turning a short-lived morale poster into the symbol for empowering women.

That transformation demonstrates how images can take on new meanings over time. As Kimble and Olson note, the modern popularity depends on how viewers reinterpret its visual symbols. The confident pose and slogan now suggest resistance to inequality rather than simple wartime efficiency. By reclaiming the image, later generations of women gave it a political power that Miller never intended. This evolution from internal factory poster to feminist emblem reflects the shifting social landscape of American gender roles.

While the poster’s immediate impact was symbolic, its long-term consequences connect to real economic change. Economists Areti Bellou and Eugenie Cardia show that women who joined the workforce during World War II experienced lasting effects on their employment opportunities and career paths.¹ Exposure to wartime industrial jobs increased their likelihood of remaining in paid work and moving into better occupations after the war. The so-called “Rosie the Riveter” generation helped pave the way for greater female participation in the postwar economy. The poster, therefore, represents not only the call to serve during a national emergency but also the beginning of a slow transformation in women’s roles in American society.

To this day the poster continues to resonate because it captures the contradiction and promise of its era. As Santana explains, wartime propaganda empowered women while also trying to contain that empowerment.² Miller’s bold design reflects both impulses: strength within limits, independence within a framework of duty.. It stands as a reminder that cultural symbols are never fixed but evolve as people reinterpret them to express new hopes and struggles.

[1] Areti Bellou and Emanuela Cardia, “Occupations after WWII: The Legacy of Rosie the Riveter,” Explorations in Economic History 62 (2016): 124–42, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eeh.2016.03.004.

[2] María Cristina Santana, “From Empowerment to Domesticity: The Case of Rosie the Riveter and the WWII Campaign,” Frontiers in Sociology 1 (2016), https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2016.00016.

[3] James J. Kimble and Lester C. Olson, “Visual Rhetoric Representing Rosie the Riveter: Myth and Misconception in J. Howard Miller’s ‘We Can Do It!’ Poster,” Rhetoric and Public Affairs 9, no. 4 (2006): 533–69.

[4] Bellou and Cardia, “Occupations after WWII,” 130.

[5] Santana, “