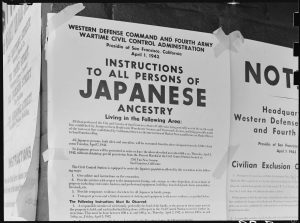

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, authorizing the U.S. Army to designate “military areas” from which any person could be excluded. Though the order did not explicitly name any ethnic group, it was used almost exclusively to remove and incarcerate Japanese Americans from the West Coast. Over 120,000 men, women, and children—two-thirds of them U.S. citizens—were forced from their homes and placed in remote, fenced “relocation centers.” This document, issued under the guise of national security following Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, represents one of the most severe violations of civil liberties in U.S. history. 1

The order must be understood within the broader context of racial discrimination and wartime hysteria in early twentieth-century America. Anti-Asian prejudice on the West Coast long predated World War II. As early as 1913, California passed laws barring Japanese immigrants from owning land, and the 1924 Immigration Act effectively ended Japanese immigration altogether. Despite their contributions to agriculture and commerce, Japanese Americans were widely viewed as perpetual foreigners. When Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in December 1941, this entrenched racism merged with fear and economic jealousy, creating the political momentum behind mass removal. As historian Brian Masaru Hayashi argues in Democratizing the Enemy, federal officials used wartime conditions to “reshape” Japanese American identity under the pretext of protecting democracy itself, meaning they sought not only to confine Japanese Americans but to actively remake them into what the government considered loyal and properly assimilated citizens. This involved loyalty questionnaires, segregation policies, and cultural pressure within the camps that attempted to redefine people’s political beliefs, social identities, and relationship to the state—all carried out through coercive wartime authority. 2

The language of Executive Order 9066 itself is cold and bureaucratic, masking the enormity of its human cost. Phrases such as “prescribe military areas” and “exclude any or all persons” frame the action as a matter of administrative necessity rather than constitutional violation. The order’s vague legal wording— “whenever he deems such action necessary or desirable”—granted sweeping discretionary power to military commanders like General John L. DeWitt, who later declared, “A Jap is a Jap.” 5 The lack of explicit mention of Japanese Americans reveals both political calculation and moral evasion: by keeping the text race-neutral, Roosevelt could deny discrimination even as his administration implemented a racially targeted policy. 1

The intended audience for this order was not the public but government agencies and military officials, yet its consequences reached every corner of Japanese American life. Entire communities on the West Coast were uprooted within weeks, forced to abandon homes, farms, and businesses—losses later estimated at billions of dollars. As documented in The American Public’s Reaction to the Japanese American Internment, wartime propaganda and fear led many Americans to accept incarceration as a necessary sacrifice for victory. 3 Newspapers, political leaders, and civic groups often framed removal as a patriotic act rather than an injustice. 6

The human toll of this policy extended far beyond the war years. Psychologists Donna Nagata, Jacqueline Kim, and Kaidi Wu describe in The American Psychologist how the trauma of incarceration persisted across generations, producing what they call “intergenerational trauma.” 4 Families who experienced forced removal internalized shame and mistrust toward government institutions, effects that rippled through Japanese American identity for decades. Only in 1988 did the U.S. government formally apologize and provide symbolic reparations under the Civil Liberties Act, acknowledging that the incarceration was motivated by “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.” 4

Viewed today, Executive Order 9066 reveals as much about the fragility of democracy as it does about wartime fear. It shows how quickly constitutional rights can be suspended when prejudice and panic override principles. Yet it also speaks to resilience: despite suffering wrongful imprisonment, Japanese Americans rebuilt their lives and, in many cases, were even drafted out of the camps and sent to fight for the very nation that denied them freedom. Units like the 442nd Regimental Combat Team became some of the most highly decorated in U.S. military history, while others resisted the draft on principle, arguing that it was unjust to demand loyalty without restoring their rights. Their sacrifices on the battlefield, combined with the long legal and political struggle waged after the war, ultimately helped build the momentum for redress. This decades-long fight culminated in the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, in which the U.S. government formally apologized for the incarceration and provided monetary compensation to survivors. As a historical artifact, the order stands as both a cautionary document and a reminder of the enduring need for vigilance in protecting civil liberties, especially in times of national crisis.

Citations

- National Archives, Executive Order 9066: Resulting in Japanese-American Incarceration (1942), Milestone Documents, https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/executive-order-9066, accessed November 6, 2025.

- Brian Masaru Hayashi, Democratizing the Enemy: The Japanese American Internment (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2004), 45.

- “The American Public’s Reaction to the Japanese American Internment,” West Virginia Historical Review 1, no. 1 (2017): 97, https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/wvuhistoricalreview/vol1/iss1/8/.

- Donna K. Nagata, Jacqueline H. J. Kim, and Kaidi Wu, “The Japanese American Wartime Incarceration: Examining the Scope of Racial Trauma,” American Psychologist 74, no. 1 (2019): 364-367, https://operations.du.edu/sites/default/files/2021-07/processing%20cultural%20trauma.pdf.

- Santa Cruz Public Libraries. “Executive Order 9066.” Santa Cruz Public Libraries: Local History Digital Collections. https://history.santacruzpl.org/omeka/items/show/134629. Accessed November 25, 2025.

- Verso Books. “Japanese Internment and the Media.” Verso Blog. https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/news/3018-japanese-internment-and-the-media, accessed November 25, 2025.

- National Archives. “World War II: AANHPI Planning Documents.” National Archives: Asian American and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (AANHPI) Records During World War II. https://www.archives.gov/research/aapi/ww2/planning, accessed November 29, 2025.