Bernhard Gillam, known for his critiques of big business and political corruption, created the political cartoon “The Protectors of our Industries” in 1883, a time when the United States experienced a big change in the economy, society, and culture. Gillam was well known at the time for his cartoons that exposed the powerful and stood with the average workers. This period is referred to as the Gilded Age, and it saw the emergence of wealthy elites from the rapid urbanization and industrialization. Shi et al. (2025) further explains this as a “social, economic, and political gap between the powerful and the powerless, the haves and have-nots.” [1] This was all due to the improvements in technology: the development of railroads and large-scale manufacturing. As a result, the everyday lives of Americans changed, and new opportunities were present for the lower working class but also focused the wealth on only a few individuals. Which created a large gap between the classes. Adler noted that “the rich, the aspiring, the nearly poor, men and women, oldsters and infants wore diamonds.” [2] So, while more opportunities were created during this time, the separation between the wealthy and the rest of society grew as they were benefiting from the working class, as represented in this cartoon.

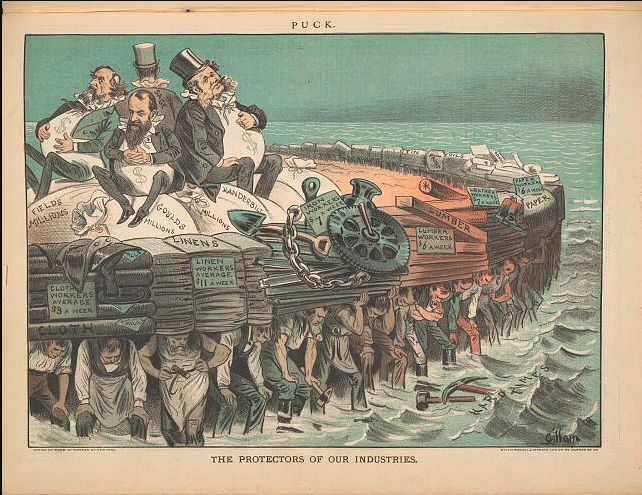

Looking at Gillam’s piece, he illustrates four of the major industrialists at the time including Cyris Field, Jay Gould, William H. Vanderbilt, and Russell Sage. They are comfortably sitting on large sacks which are labeled “millions” and holding their round full stomachs that have money symbols on them. This shows the comfort and ease they felt due to their financial status and that they were “full” from their profits. Below these wealthy men are a diverse group of workers who are carrying a large raft on their backs that is made of industrial products including lumber, linen, and cloth. Their physical appearance is very opposite to the wealthy as they look exhausted and malnourished. Each worker is also labeled and categorized with a particular wage and trade. For example, iron and leather workers earn seven dollars per week, and linen workers earn eleven dollars a week. So, while the wealthy are sitting on millions, the group who is working the hardest physically is barely making enough to support a family for the week. Additionally, there are tools and the words “hard times” written in the choppy ocean waters. This shows that during this time, there was great uncertainty as the industrial process is based on this working class. This is further explained by Greene, who states that this period was built “from the bottom up” through labor of the working class whose “movability was essential to the empire’s strategy”. [3] Gillam’s cartoon shows the dangers that are present with labor exploitation where economic growth and stability are based solely on the working class. Even though this is true, their work still goes unnoticed, as represented by their faces being hardly visible in Gillam’s cartoon.

Bernhard Gillam titled this cartoon, “The Protectors of our Industries” in a way that reflects this system, that he is warning against. During this time, the rich business owners supported protectionist policies which “favored American manufacturers by effectively shutting out foreign imports, thereby enabling U.S. corporations to charge higher prices for their products.” [4] Campbell explains that by the end of the century, elite New Yorkers had an “unprecedented influence” which made the country the “most bourgeois of all nineteenth-century societies.” [5] He further explains the process that led to this, which is visualized in Gillam’s cartoon, where there is a clear distinction between the wealthy and working class. So, this title highlights the cover and protection that the wealthy provide but shows the struggles that come with it, inequality between the classes during the Gilded Age.

Works Cited:

[1] Shi, David E., Daina Ramey Berry, Joe Crespino, and Amy Murrell Taylor. America: A Narrative History. 13th ed. W.W. Norton and Company, 2025.

[2] Adler, Jeffrey S. 2002. Gilded city: Scandal and sensation in turn-of-the-century new york / the monied metropolis: New york city and the consolidation of the american bourgeoisie, 1850-1896. The Journal of American History 88, (4) (03): 1554-1555, https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/gilded-city-scandal-sensation-turn-century-new/docview/224896297/se-2, accessed October 24, 2025.

[3] Greene, Julie. 2016. MOVABLE EMPIRE: LABOR, MIGRATION, AND U.S. GLOBAL POWER DURING THE GILDED AGE AND PROGRESSIVE ERA. The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 15, (1) (01): 4-20, https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/movable-empire-labor-migration-u-s-global-power/docview/1762313271/se-2, accessed October 24, 2025.

[4] Shi, David E., Daina Ramey Berry, Joe Crespino, and Amy Murrell Taylor. America: A Narrative History. 13th ed. W.W. Norton and Company, 2025.

[5] Campbell, Ballard C. 1999. Understanding economic change in the gilded age. Magazine of History 13, (4) (Summer): 16, https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/understanding-economic-change-gilded-age/docview/213732182/se-2, accessed October 24, 2025.