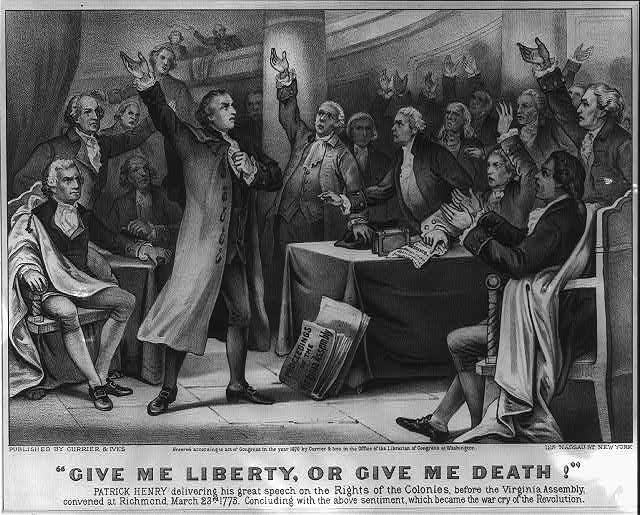

Patrick Henry’s iconic “Give Me Liberty or Give Me Death” speech, delivered on March 23, 1775, at St. John’s Church in Richmond, Virginia, marks one of the most defining moments in American history. Henry, a lawyer and influential Virginia statesman, wrote this speech to persuade his fellow colonists that war with Britain was not only inevitable but morally justified. This address occurred against the backdrop of escalating tensions between Britain and its American colonies, tensions driven by Britain’s increased taxation and tighter regulation, exemplified notably by the Stamp Act and the subsequent colonial resistance, as highlighted in our textbook with examples like the Stamp Act Congress and the widespread non-importation agreements.

Colonists reacted strongly against British oppression, revealing the moment that made Henry’s speech not just relevant but necessary. Colonists increasingly viewed British rule as a direct threat to their liberty. Patrick Henry captured this widespread colonial anxiety, channeling it into a call for immediate and unified action. His famous concluding words, “Give me liberty, or give me death!” encapsulate the urgency and gravity felt by many colonists during this era. Earlier in the speech, Henry asks, “Is life so dear, or peace so sweet, as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery?” This stark rhetorical question underscores the absolute moral terms in which Henry framed the choice facing the colonies.

Historian Charles L. Cohen notes that one key to Henry’s rhetorical effectiveness was his strategic use of religious themes. Cohen argues, “Henry infused his oratory with religious allusions, framing the revolutionary struggle as a sacred cause and employing providential logic that resonated deeply with his audience’s moral convictions” (Cohen 1981, 680). Cohen further emphasizes how Henry’s appeal to divine authority elevated the struggle, turning it into “a moral imperative as well as a political necessity” (Cohen 1981, 682). For example, Henry’s assertion that “There is a just God who presides over the destinies of nations” explicitly weaves religious belief into his call to arms, deepening its emotional resonance.

Jeffery H. Richards provides further insights into another critical layer of Henry’s rhetoric, highlighting its classical roots. Richards draws strong parallels between Henry’s language and Roman themes of honor, bravery, and noble self-sacrifice, particularly noting how Henry intentionally drew parallels between American resistance and the heroic ideals associated with Cassius’s Roman suicide. Richards emphasizes, “Henry explicitly drew upon the legacy of Roman figures to frame resistance as noble and heroic, rooted in classical virtue” (Richards 1980, 264). Such classical references strategically validated revolutionary ideals as part of a historical tradition, as seen when Henry proclaims, “Suffer not yourselves to be betrayed with a kiss,” invoking betrayal and loyalty in ways reminiscent of Roman narratives.

Michael George’s examination complements this perspective, emphasizing Henry’s rhetorical mastery. George observes that Henry’s effectiveness came from emotional appeals, strategic use of rhetorical questions, and compelling word choices. George notes, “Henry employed rhetorical questions to provoke contemplation and emotional intensity, prompting his listeners to envision the grim consequences of continued subjugation under British rule” (George 2009, 353). Henry’s chilling warning, “The next gale that sweeps from the north will bring to our ears the clash of resounding arms!” powerfully evokes the looming inevitability of conflict.

Our textbook supports these analyses by emphasizing the practical significance of Henry’s deliverance. By 1775, tensions had reached a tipping point. Britain’s harsh response to colonial unrest convinced colonists like Henry that political dialogue had failed. In his speech, Henry passionately argued against peaceful reconciliation illusions, explicitly stating, “We must fight!” and warning his peers not to trust Britain’s false promises. This mirrors the textbook’s discussion of the breakdown of efforts like the Olive Branch Petition, illustrating how colonists had little choice but to move toward armed resistance. Furthermore, the textbook’s detailing of the Continental Association’s efforts underscores Henry’s point that collective, decisive action was urgently needed.

Henry’s speech, therefore, offers profound insights into revolutionary America’s character and concerns. It was not merely political rhetoric but an articulation of deeply held beliefs about liberty, honor, and moral duty. The blending of religious zeal, classical virtue, and emotional urgency galvanized Henry’s audience and captured the spirit of a population in unrest. His words vividly show how revolutionary ideals transcended mere political disagreements, evolving into powerful emotional and moral convictions that demanded action.

The immediate impact of Henry’s speech was profound. According to historical accounts, including those referenced in our textbook, the Virginia Convention was deeply moved, and the motion to arm the Virginia militia passed by only a few votes, a razor-thin margin that demonstrates both the speech’s influence and the gravity of the decision. Henry’s impassioned call helped push Virginia firmly onto the path of revolution, demonstrating his speech’s effectiveness not just as a rhetorical masterpiece but as a catalyst for real political change.

Ultimately, Patrick Henry’s “Give Me Liberty or Give Me Death” speech represents a turning point, hardening revolutionary sentiment and propelling American colonists toward decisive action. Its lasting significance lies in Henry’s ability to articulate a vision of freedom that was political, moral, and spiritual. A vision compelling enough to spark the flame of the American Revolution. Therefore, his speech stands as a powerful historical testament to rhetoric’s role in shaping American identity and galvanizing a nation toward independence.

Work Cited

Charles L. Cohen, “The ‘Liberty or Death’ Speech: A Note on Religion and Revolutionary Rhetoric,” The William and Mary Quarterly 38, no. 4 (October 1981): 679–692. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1918911.

Michael George, “Patrick Henry: From Strong Statements to a Strong Cause,” The Corinthian 10, no. 16 (2009): 351-358. Knowledge Box

Richards, Jeffery H. “Patrick Henry’s ‘Liberty or Death’ Speech and Cassius’s ‘Roman’ Suicide.” Early American Literature 15, no. 3 (1980): 263–266. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4248229

Shi, David E. America: A Narrative History, Brief 12th ed., vol. 1 (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2022), 125–173.