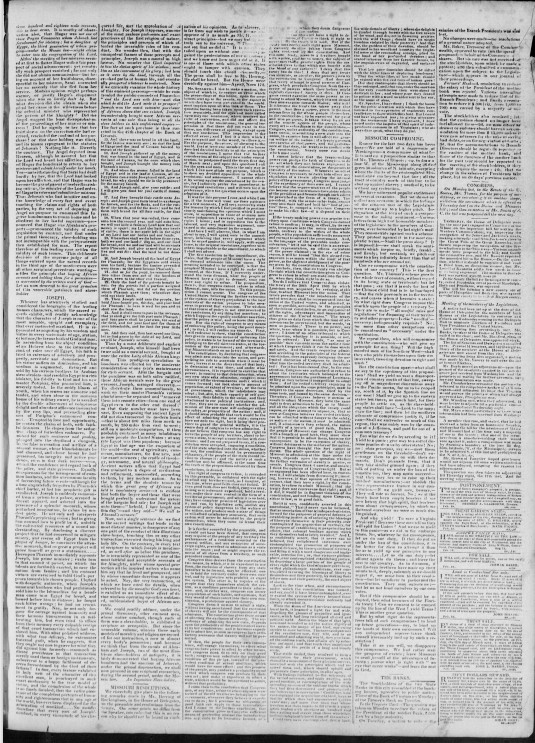

The Richmond Enquirer and the Missouri Compromise

This piece, which was published in the Richmond Enquirer on February 10, 1820, provides a glimpse into how pro-slavery beliefs were publicly justified and shared during the height of the Missouri Compromise debates. The article uses religious language to support its claim that slavery is consistent with biblical teachings and, as such, cannot be refuted by moral or legal arguments.¹

The Richmond Enquirer was one of Virginia’s most influential newspapers in the 19th century, and its editor, Thomas Ritchie, was among the most powerful political journalists of his time. According to the Virginia Print Culture Lineages display at the Library of Virginia, the publication, which was founded in 1804, became “the most important Democratic organ in the South before the Civil War.”² Over time, its editorial positions changed, but by 1820, they were solidly based on supporting Southern institutions, especially slavery.

In American history, the Missouri Compromise was a turning point. The question of whether slavery would be permitted to spread westward threatened to split the country, and the balance of power between slave and free states was in jeopardy. “The institution of slavery existed in the days of our Savior and was not denounced by him,” the Enquirer wrote in an editorial during this national crisis.³ The post uses the Bible as a moral justification to silence critics, implying that slavery was not only historically widespread but also approved by God.

This appeal to religious justification is not accidental. Thomas Ritchie continued to influence Democratic talking points after relocating from Richmond to Washington in 1845 to serve as editor of The Union newspaper. He was “a prominent spokesman for the Democratic Party and its policies,” according to the Library of Virginia, especially during the emergence of partisan media.⁴ In addition to reflecting his own views, his editorial choices also represent the larger position of Southern Democrats who based their political and economic structures on slavery.

Beyond Ritchie’s own paper, this article discusses how the press was used as a political instrument. The Enquirer and similar publications are described as “primary sources for understanding how Virginians viewed political and cultural conflicts” by the Virginia Chronicle, a digital site that contains these old newspapers.⁵ These articles participated in forming the story rather than acting as objective journalists.

A closer examination of the editorial’s wording reveals the purposeful use of language that hides slavery under almost academic terminology. The account of Joseph, for instance, who was “sold into slavery by his brethren,” is cited in the essay not as a tragedy but as more evidence that slavery is “in accordance with Divine Law.” This is not just a debate; it is a reinterpretation of the Bible for political purposes.

This approach is typical of the Enquirer under Ritchie’s direction. By establishing a worldview in which “masters and slaves both served the divine plan,” as one historian described it, he continuously sought to use moral and intellectual justifications to justify Southern actions. By carefully crafting the article to convince readers that their social order was both legal and moral, it becomes more than just a mirror of public opinion; it also shapes it.

This editorial offers an important perspective on the extent to which slavery affected the South’s political, religious, and cultural fabric. It also serves as a reminder that the conflicts that would ultimately result in civil war were significantly shaped by ideas and the channels through which they were distributed.

Footnotes:

- Richmond Enquirer (Richmond, VA), February 10, 1820, p. 3, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers, accessed April 9, 2025, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84024735/1820-02-10/ed-1/seq-3/.

- “The Enquirer,” Index of Virginia Printing – Newspaper Lineages, Library of Virginia, accessed April 9, 2025, https://www.lva.virginia.gov/virginiaprint/lineages/lineage.php?id=81.

- Richmond Enquirer (Richmond, VA), February 10, 1820, p. 3, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers, accessed April 9, 2025, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84024735/1820-02-10/ed-1/seq-3/.

- “Thomas Ritchie,” Library of Virginia: Union or Secession—Virginians Decide, accessed April 9, 2025, https://www.lva.virginia.gov/exhibits/political/thomas_ritchie.htm.

- “Richmond Enquirer,” Virginia Chronicle: Digital Newspaper Archive, accessed April 9, 2025, https://virginiachronicle.com/?a=cl&cl=CL1&sp=RE.