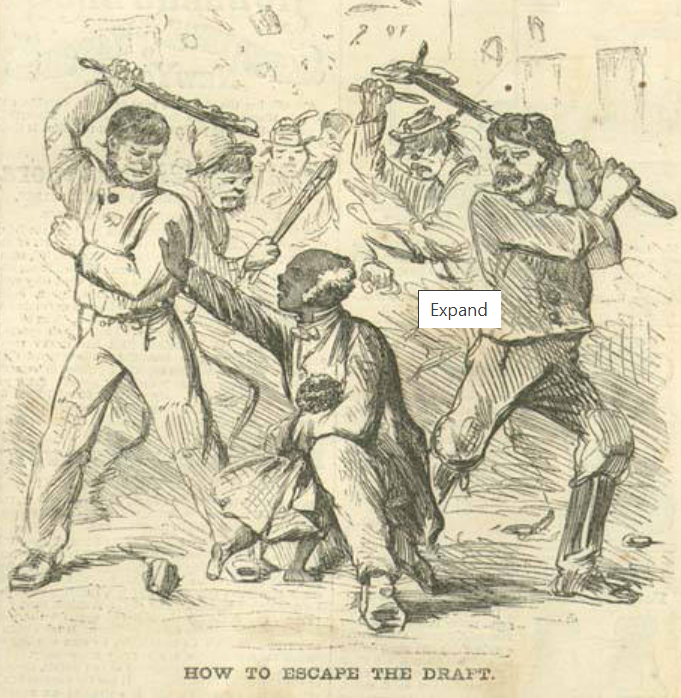

Political Cartoon: How to Escape the Draft

https://gettysburg.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p4016coll2/id/16/

The political cartoon How to Escape the Draft was created in the midst of one of the most volatile moments of the Civil War, the 1863 New York City Draft Riots. The cartoon appeared in Harper’s Weekly, a widely circulated publication known for its sharp visual commentary on current events. The cartoon captures the deep racial and class conflicts that exploded in response to the Union’s conscription policy, exposing how many white Northerners lashed out violently against Black Americans rather than the system itself.

To properly understand the cartoon, it is vital to be aware of the 1863 Enrollment Act. The law gave the federal government the power to draft men into military service, but it also meant a drafted man could pay $300 to avoid service by hiring a substitute. This policy enraged working-class white men, immigrants, or those who couldn’t afford such a fee. At the same time, the war’s evolving purpose toward emancipation caused resentment among whites who feared they would now have to compete with newly freed Black workers. As historian James W. Geary explains, “The commutation provision became the focal point of class-based criticism, especially from those who believed the war was becoming ‘a rich man’s war and a poor man’s fight.’”¹ That fear, combined with economic frustration and longstanding racism, helped trigger the Draft Riots. Joanna Cohen stated, “African Americans who were the target of lynch mobs, had been severe. Riots erupted on July 13, 1863, and the violence persisted for five days. Published death tolls stood at 119, although eyewitnesses, such as Jeff Whitman, Walt Whitman’s brother, reckoned that the number of rioters who had paid for their actions with their lives was closer to four hundred.”² In the center of the cartoon, an African American man cowers while several white men attack him with sticks and clubs. The irony in the caption, “How to Escape the Draft,” is bitter and intentional. It mocks the idea of honor or patriotism by showing how some white Northerners responded to the draft. Instead of resisting government injustice, they directed their anger toward innocent Black civilians. According to Jonathan Well, the 1863 Draft riots were “more about lashing out at Black people than opposition to the draft, though to be sure the mob was prompted also by conscription and the fact that wealthy men could pay their ways out of service.”³ The cartoon became very disturbing, showing that racial violence was still alive despite the country’s past victories.

All through the cartoon, there is chaos. The attackers are mid-swing with faces twisted in anger, creating an overwhelming sense of mob frenzy. While The African American man’s body language is the opposite, he is defensive, outnumbered, and vulnerable, highlighting his complete lack of protection in a society that claims to fight for liberty. In the background, objects are flying in the air. This adds to the chaos, echoing the real-life burning and looting that marked the riots. Since there are many attackers and one victim, it represents the cowardice and imbalance of power from the attackers. This cartoon isn’t just a snapshot of one ugly episode. It’s a commentary on the contradictions of the war itself. While the Union fought to end slavery, systemic racism was still deeply embedded in Northern society. The drawing proves that the Civil War era wasn’t just a clash between the North and South, it was a national reckoning with white supremacy.

How to Escape the Draft forces us to confront the uncomfortable truth that the fight for Black freedom wasn’t confined to battlefields. Their freedom was fought and resisted in city streets, in newspapers, and in the minds of everyday Americans

Footnotes:

- James W. Geary, “The Enrollment Act and the 37th Congress,” The Historian 46, no. 4 (1984): 582, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24445478.

- Joanna Cohen, “Reckoning with the Riots: Property, Belongings, and the Challenge to Value in Civil War America,” Journal of American History 109, no. 1 (June 1, 2022): 71, https://doi.org/10.1093/jahist/jaac118.

- Jonathan Daniel Wells, “Inventing White Supremacy: Race, Print Culture, and the Civil War Draft Riots,” Civil War History 68, no. 1 (2022): 56