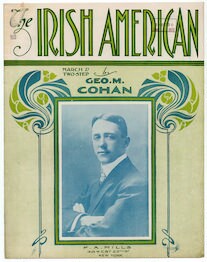

The Irish American[1], piano sheet music is a 1905 composition by George M. Cohan, a famous Irish Catholic American entertainer who became a pinnacle for Catholic Irish Americans during an era of oppression. In many ways, Cohan’s contributions embraced widespread Irish American heritage and pride. Through sound, the piece resonates the pure historical significance of the immigration of the Irish into the American lifestyle, and highlights how despite all their trials and tribulations, they created and preserved a foundation to continue to succeed through all forms of prejudice.

George M. Cohan, (1878-1942), was a brilliant entertainer, playwright, composer, lyricist, actor, singer, dancer and theatrical producer of Irish descent. His parents were travelling vaudeville actors, and they were known for the act “The Four Cohans”, which starred himself, his sister, and his parents. To put his career into perspective, he starred in, created, and produced over 3 dozen Broadway musicals, wrote and produced over 50 televised shows, and successfully published over 300 songs. As an Irish American, his success was incredibly well known, as he set a benchmark not only for Irish Americans all throughout the country, but for anyone with a work ethic and drive to succeed, showing that with constant effort, stories like his are possible. He left an indelible imprint on the entertainment business, being dubbed “the father of American musical comedy”, and also called “the man who owned Broadway.” In addition to all the commemorations that have been issued in remembrance of Cohan’s lifelong contributions to the Broadway and entertainment businesses respectively, the most notable one, a statue of Cohan in Times Square in New York City, can still be seen today.

The Initial Irish immigrants, which would have been Cohan’s parents, left a rural lifestyle in a nation devoid of modernity. Many immigrants found themselves unprepared for the industrialized, burgeoning urbanization that was widespread in the United States. However, that did not stop them from finding their inevitable success and reputation. At the time, largely poor and living in abject poverty, many initial Irish immigrants left for a land they envisioned was full of promise, with no knowledge of what they were about to encounter. Following the adverse effects of such events like the potato famine, they often had zero dollars when they left, only the clothes on their backs and a fierce work ethic. Yet still they came in a multitude of waves, bringing as many as 4.5 million Irish onto American shores between the years of 1820 through 1930. During this time, the Irish represented just over a total third of the conglomerate of international immigrants living in the U.S. However, they were not welcomed with open arms upon arrival. Considering the fact that the general American people believed that Ireland was a desolate disease-ridden land, as Irish families moved into local neighborhoods, previous tenants felt the desire to leave, fearing the so called unclean and unsanitary people and the diseases they brought with them. In turn, a host of social problems arose.

Though the wave of Irish newcomers were not the only ethnic group to face a host of maltreatment, they still faced substantial hostility from the American people into the early 19th century. Most Irish were Catholic and had been specifically treated with disdain by the American Anglo-Saxon Protestants, who sought to differentiate themselves from any group of Catholic denomination. As stated by Patrick McGrath[2] in his article in the Journal of American Ethnic History, entitled “Secular Power, Sectarian Politics: The American-Born Irish Elite and Catholic Political Culture in Nineteenth-Century New York,” he stated that “mass immigration at midcentury, coupled with growing nativist persecution of the Catholic Church, forced these elites to navigate a middle ground between the secular world of New York politics and the rising sectarianism of the Irish immigrant community.” In turn, the Catholic subculture that was beginning to emerge was being built on the values and efforts of Irish born tenants, farmers, lawyers and politicians.

This Catholic subculture allowed for a platform that Irish Americans viewed as a feasible way to properly assimilate into the American society. Specifically, in densely populated areas such as New York, or Boston, most of the Catholic community was of Irish descent. At this period in American Catholicism, with such a dominant Irish face, Catholicism became the most effective tool for Irish Americans to show the general American public exactly who they are, and not who they were thought to be. By as early as 1914, Catholicism became the most active and useful device for the Irish American people in terms of integration. Moreover, thanks to the proper and diligently guided leadership of Irish American Catholics, they no longer needed to adopt the defensive stance that early initial immigrants were forced to use. This new fervent wave of Irish American Catholicism became the catalyst for leveling equality in an American society. As stated in Elizabeth McKillen’s[3] essay in Diplomatic History entitled “Ethnicity, class, and Wilsonian internationalism reconsidered: the Mexican-American and Irish-American immigrant Left and U.S. foreign relations”, the devoutness displayed by Irish American Catholics became viewed as a dynamic “articulation of patriotism.” The culmination of Catholic Irish efforts as such are what became the breeding ground for famous stories and songs such as “The Irish American”, by George M. Cohan, to be put in place to be a part of and inspire Irish American heritage and tradition.

[1] The Library of Congress, Notated Music, https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.100001095/, accessed February 17, 2020.

[2] Patrick McGrath, “Secular Power, Sectarian Politics: The American-Born Irish Elite and Catholic Political Culture in Nineteenth-Century New York,” Journal of American Ethnic History, Vol. 38 Issue 3 (2019): 36.

[3] Elizabeth Mckillen, “Ethnicity, class, and Wilsonian internationalism reconsidered: the Mexican-American and Irish-American immigrant Left and U.S. foreign relations,” Diplomatic History, Vol. 25 Issue 4 (2001): 533.