Like in Tunisia, Egyptians were frustrated with rising unemployment. This frustration was very palpable on college campuses and among those who were college educated. It was difficult for this population to find jobs. The main difference between Egypt and Tunisia was that the protesters initially rallied because they wanted to publicly express their dissatisfaction with police brutality, organized by President Hosni Mubarak. In addition, protesters were angered by Mubarak’s state-of-emergency laws, the complete lack of the development of political freedoms and liberties, including freedom of speech, and economic matters like rising inflation paired with low wages.

The violence really was centralized in the protests that occured in Cairo and near the Suez Canal. This is where the security forces met the protesters with violence in order to silence the dissents.

President Hosni Mubarak

Hosni Mubarak became the President of Egypt in a unique way. The previous president, Anwar Sadat, was assassinated in 1981. When Mubarak gained control, he immediately declared a state of emergency in order to quell the unrest during that time. Mubarak was more willing to cooperate and engage in diplomatic relations with the West–specifically the United States. Under Mubarak, the Egyptian government maintained relatively-peaceful interactions with Israel and also quieted radical Islamic ideology. Mubarak remained in power since 1981, and eventually considered passing his position on to his son in 2000. This is clearly not democratic. Again, in order for a society to be considered a democracy, it is important that the society has open, fair, and free elections. Mubarak was very similar to Ben Ali. Although he held elections during his tenure, Mubarak was often the only candidate. In addition, all the other positions Egyptians were allowed to vote for only had candidates from one party–the same one President Mubarak belonged to.

Emergency Law

Mubarak insisted on enacting a state of emergency after the assassination of his predecessor Anwar Sadat in 1981. Since then, with the expectation of a few months during the 1980s, the country has been in a constant state of emergency. This state allows the government more room to exercise their reign. During this time, the police and military have more right to power, constitutional rights can be suspended, the government can censor content on all platforms, and the government does not need to bring prisoners to trial–they can continue to detain them without notifying them of why they are being held. It is estimated that during 2010, anywhere between five thousand and ten thousand people could have been detained with their habeas corpus rights suspended.

As Mubarak’s authoritarian reign continued, the police forces began to become more violent to political opposition, protestors, and civilians as a whole. More people began to witness the injustices perpetrated by the police forces with the development of cell phone video footage. These videos paired with witness testimony from prisoners and other Egyptians provided the country and the world with more background and evidence to the horrifying acts of brutality. The United States State Department released a Human Rights Report in 2009, which summarized their findings regarding their investigation into the reports of police brutality.

The police were under direct order from Mubarak and his administration. Mubarak created a specific branch of the national police force, the Baltagiya, or officers who blended in with the typical civilian in undercover attire. The Egyptian Organisation for Human Rights documented that there were over five hundred and sixty cases of torture and over one hundred and sixty deaths while in custody of the Baltagiya from 1993-2007.

On June 6, 2010. He was taken into police custody that night. The police argue that Sayed died after choking on hashish during a police chase. His friends and family disputed those claims. In fact, his body post mortem showed astounding physical damage. It was clear that he was beaten. Photographs of his mutilated body were posted to a Facebook page titled “We are all Khaled Said.” This page received nationwide attention and ignited a conversation. The country discovered that the majority of civilians were outraged at the current conditions.

This Facebook page was not the only thing that motivated protesters to take to the streets. First-hand videos taken by people on the ground, paired with eyewitness testimony and stories shared on blogs began to bring organized protests to fruition. What at first were peaceful demonstrations, spiraled into bloody brawls initiated by police and military forces. From January to February of 2011, these protests raged on. On January 26, Jack Shanker, a reporter for The Guardian was arrested by police while filming the demonstrations. While in custody, he witnessed other Egyptians being subject to torture at the hands of the police.

Egyptians preparing for their Arab Spring looked to Tunisia for inspiration. A few young men lit themselves on fire, much like Mohamed Bouazizi. On January 25 2011, students organized mass protests on the holiday–National Police Day. They adopted this day because it was the perfect way to shed light upon their main belief, to have Mubarak put an end to the violent methods adopted by police. In addition, they also wanted to abandon the constant state of emergency law, instate term limits for the president, and also an end to political corruption. Twenty-six year old blogger Asmaa Mahfouz posted a video in which she called upon the Egyptian people to participate in these Police Day Protests in Cairo’s Tahrir Square. This was one of the first utilizations of social media by the protestors to really boost their message and gain numbers in the protests out in the streets. Video blogging and social media posts became the new norm where Egyptians shared all the breaking news and updates within the demonstrations. In fact, the Facebook event page for the Police Day protests attracted eighty-thousand people to Tahrir Square. On the 27th of January, the government began to censor the internet by blocking and shutting down servers. Mubarak became wise to the fact that the internet could potentially bring about his downfall.

Revolutionary Art

“…in Egypt, where the Ministry of Culture controlled all public expression, protest art was hard to find — at least until this January, when 18 days of mass revolts toppled President Mubarak’s regime and unexpected freedoms flourished, including the right to make art.” –The Atlantic, October 3, 2011

Before the protests were sparked, Egyptians turned to art. Young protesters took to the streets to paint their ideologies on the walls. Their desires for a more free and just society were depicted in works that were stories high. The streets were theirs for the taking. Yes, the government can paint over the artwork, but even if at least for a few moments, the artwork survives and is admired. It sparks conversation between generations and among classes.

Ganzeer & “The Tank vs. The Biker”

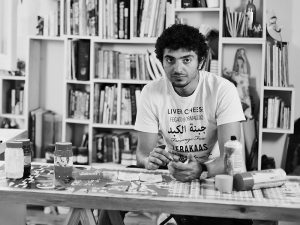

Ganzeer is one of the most well-known street artists in not just Egypt, but also the world as well. Ganzeer translates to “bicycle chain” (New York Times). When asked about why he chose that particular name for himself, Ganzeer said, “We are not the people pedaling, but we can connect ideas and by doing this we allow the thing to move.”

His signature art medium is “concept pop, a brand of cultural insurgency that utilizes the aesthetics birthed by Pop Art in tackling the subject matter typically ascribed to Conceptual Art. …[It’s] a little bit of everything: stencils, murals, paintings, pamphlets, comics, installations, graphic design and more” (New York Times).

Up until May 9, 2014, Ganzeer completed mural after mural after mural in Cairo, the city where he grew up. On this date, his pseudonym had been exposed on national television, and his true identity had been compromised. He fled to the United States, and has since lived in both New York and Los Angeles (New York Times).

Pictured above is arguably Ganzeer’s most significant work of art in the scheme of the Arab Spring protests in Egypt. Titled, “The Tank vs. Biker”, it depicts a man on a bicycle carrying bread across from a large Egyptian tank. Depending on interpretation, it certainly has a number of messages to convey. The tank can symbolize the oppression and violence perpetrated by the government-run military and police forces. The young man on the bike is meant to represent the average Egyptian. Is he protesting the regime simply by carrying on with his everyday life? Is he just meant to symbolize how any average Egyptian could rise up against the military and hold his own? Or, perhaps the tank pointed at the bike rider is meant to show how the usual Egyptian way of life is under attack.

A few weeks after the original mural was completed, the military engaged in an act of censorship and painted over the portion of the mural that depicted the young boy on his bike. In retaliation, an artist who goes by Mohammed Khaled painted a caricature of an Egyptian soldier, eating something with blood everywhere. This has been interpreted to be symbolic of the military killing freedoms by participating in acts such as this. Some even go as far as to say that the soldier ate the boy on the bike. That would depict how the government is destroying Egyptians’ current way of life.

SuzeeInTheCity

SuzeeInTheCity is a blog run by Soraya Morayef, an Egyptian woman who holds a deep appreciation for protest art in Cairo. Her blog acts as a sort-of online curiation, in which she will take photographs of murals and art created around the city, and then describe each piece in a few lines and include her own personal commentary. Sometimes she knows which artist created which piece, but most of the time, a lot of the artwork remains unclaimed. The following pieces are all from her blog.

This piece depicts a boy drawing back a catapult. It was done with spray paint and stencils, a common theme among street art. The increased ability for artists to create stencils via computer or digital programs allows for more intricate stencils, which in turn create more in depth works. The artist is unknown. However, the fact that it is a boy depicted makes me inclined to believe that the artist wanted to convey that the cause the protesters are working towards will affect the future of Egypt. In other words, they’re fighting for a better future for their children.

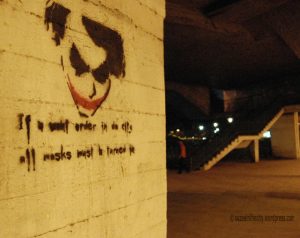

This stencil work was done by the street artist known as “The Joker”, known because of his utilization of Batman imagery. Underneath the image of the Joker, it reads, “If you want order in the city, all masks must be turned in.” I believe that the reference to the Western comic Batman is significant. Yes, it should be noted that the fact that Egyptian protesters are utilizing images of Western art is a sign that the protesters are not moving toward “Islamization” their society. It was known that the protesters actually wanted democratic components in their political systems and in their social lives. In addition, the Joker is a figure who is portrayed as a villain, but in the more recent movies, the viewer can sympathize with him. The text with the image implies that the protesters cannot hide under fake names or be afraid to go out to the streets. The biggest weapon the protesters have is that they are average citizens. They are not criminals, so then, why would they have to hide? I also then can conclude that the text is also a bit ironic. Most street artists do prefer to complete their work at night, under cloak of darkness, and usually in disguise. Aren’t the artists part of the movement, too?

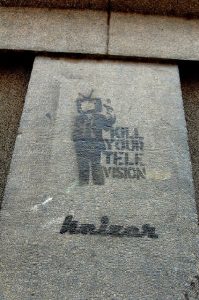

This is a smaller stencil piece, known as a “tag,” done by Keizer. The image depicts a man in a shirt and tie with a television for a head, pointing a gun at himself. The caption reads what the piece is titled, “KILL YOUR TELEVISION”. I believe this is meant to symbolize the fact that Egyptians should not blindly consume the state-run Egyptian media. In addition, I think it can also reference the fact that Egyptians need to be weary of censorship and the bias that is portrayed in the media.

Keizer is also one of the more well-known artists in the street art community. SuzeeInTheCity actually was able to accompany him on one of his projects and he participated in an interview with her. He explained why the majority of his work that uses text is in English and not in Arabic. He wants to “‘attack the upper echelons of society.'”

This is a stencil work done by artist El Teneen. It shows a tank being smashed by a red fist, on which is a crescent and a cross. The religious imagery is significant here. I believe that the cross, symbolizing Christianity, and the crescent, symbolizing Islam, is a call to unity for the two religious groups. When they work together for the common goal of defeating the state, they are more powerful than when they are alone.

This is a free-hand spray paint piece by graffiti artist known as HK, as noted by his initials. In arabic, it reads, “We are all Khaled Said.” Khaled Said was the young man who was brutally beaten by police forces in the streets. This was a common slogan utilized by protesters.

This is an image of a plant sprouting out of the ground. The plant is Arabic calligraphy and reads “revolution”, and the soil reads, “martyrs.” This is in reference to those who have given their lives to the cause. Their deaths were not in vain, and the protestors adopted their message and use it to fuel their way through the revolution. The artist is unknown.

This is another work done by just spray paint and no stencils. The artist is also unknown. The image depicts the Arabic word for “corruption” in the middle of the piece. On one side, there is a SCAF member sitting comfortably on a throne, barely chipping away at the word “corruption.” On the other side, one can see a man using a lot of force on the word “corruption, and is actually breaking apart the word. This is meant to show how the people of Egypt were doing more to topple corruption than the people in politics who claimed that they would make strides toward eliminating unfair practices in government.‘

This is a stencil work, also done by the artist El Teneen. It reads, “The people want the downfall of the regime” in calligraphy.

This is another work that is just text based, without any accompanying images. It reads, “The people and the people, one hand.” This was said by protesters after the police and military would violently attack peaceful demonstrators.

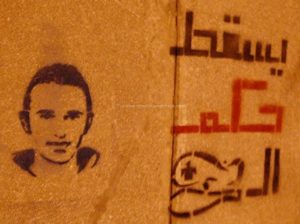

This is yet another utilization of Khaled Said, the man who was beaten to death by police. It is a stencil work done by an unknown artist. It reads, “Down with SCAF.”

This piece was an original created in 2011. The artist is once again unknown. The text reads, “Their weapons vs. ours.” On one side, there is a military weapon. On the other, there is a video camera. This emphasizes the significance of the world media reporting from Tahrir Square. The reporters showed the world what was going on during these protests, and provided documentation of the violence that was perpetrated by the police and military. In addition, I believe the camera can also be taken to represent not just a bigger, broadcasting corporation camera. Instead, I think it can show how any Egyptian with a camera of any sort can record what is going on and share it with the world.